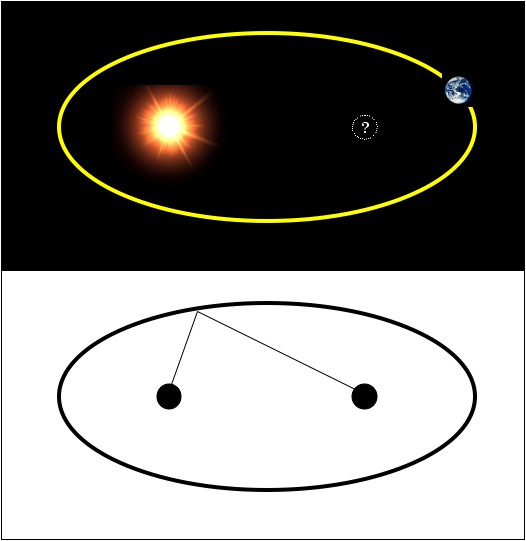

Physicist: This question always bothered me too. The short answer is: it falls out of the math. Specifically, the math of first year physics and second year calculus. The fact that the Sun is in one focus is just one of those things. It’s nothing special. Even less special is the other focus, which contains nothing at all.

Ellipses and their foci have a lot of useful properties. It so happens that an orbiting object traces out an ellipse, with the thing it orbits around at one of the focuses. Coincidence? Yes.

I can’t find a good intuitive reason why orbits are elliptical. In fact, I can’t even find a mathematical derivation. So, because it should be found somewhere, I’ll leave the derivation floating in the answer gravy.

Answer gravy: The force of gravity is usually written as . You can rewrite this using vector notation as

, where the dot on top is a time derivative. To keep the notation both standard and confusing,

.

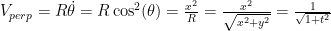

c is an “integration constant“, it can be any number. Jumping over to polar coordinates you can rewrite the usual velocity in terms of how fast you’re moving toward or away from the Sun

and how fast you’re going around

.

L is the angular momentum of the planet in question, and it’s constant. It may seem silly but, with the advantage of foresight, it’s better to solve this problem in terms of 1/R instead of R.

The choice of P and ε may seem arbitrary (and it is), but it has some historical relevance. P is called the “semi-latus recturn” and it basically describes the size of the orbit. ε is called the “eccentricity”, and it describes how lopsided the orbit is. ε=0 means the orbit is a circle, 0<ε<1 means the orbit is elliptical, and 1≤ε means that the orbit is open (not actually orbiting). For reference, the Earth’s eccentricity is ε=0.01671123 and Halley’s comet’s is ε=0.967.

D just describes what direction the far side of the ellipse points in, so it’s not actually important to the overall shape.

It turns out that this last equation relating R and θ is all you need to define an ellipse, such that the center of the system, (0,0), is at one of the foci. Here’s a proof:

An ellipse with a focus at (0,0) can be written where F is the distance from the center of the ellipse to the focus and

.

Put it all together, and you’ll find that this is definitely an ellipse with a focus at the point (0,0), the location being orbited around (like the Sun for instance).

Standard and confusing is right. Someone must have been reading Jackson recently. My favorite David Jackson story: a friend of mine met him once at a conference and asked him why he dedicated the book to his father. His reply? “So everyone would know I had one.”

Jackson has a father?

Just a curious question. Is this one of those things that you explicated that is known or is it something that you can just figure out by looking at it HAVING NEVER SEEN IT. I’m just curious. I’m a math and physics double major and I can follow the math (I’m only in my first year >.>) but I always feel stupid when someone pulls out a huge derivation like this (don’t get me wrong, I love them) but I’m always like, “is this something they thought of or is this like, written down? Should I be able to do this?” I’m not sure what I’m trying to say I guess lol.

I’d never seen a derivation, which is why mine is so clunky.

My thinking was: write down “F=MA” and go from there. Knowing that the end result is an ellipse means that the solution can be in a form that’s independent of time (it’s just a shape). I chose to used R and theta instead of x and y because the conservation of momentum has a simpler form, and it gives you a chance to get rid of the time dependence.

Also, this was my third or fourth attempt. The first ones were tumbling train wrecks. The derivations you see are almost never the first attempt, and generally it’s streamlined so much that you can barely see what the author was thinking.

In your first year it would be unusual to be able to do this. Having experience seeing tricks other people use is in derivations is very important. When a professor is deriving stuff it helps (both of you) to ask “why did you do that?” or “what is the goal in this step?”. Harass them during office hours as often as you can, and keep a dialog open while they work through problems. It takes the mystery away from the whole process.

Orbits are elliptical, because Kepler told so and Newton proved them to be so!!!

However, simple mechanics tells us that no free body can orbit around another moving body in closed geometrical path. [Central body of a planetary system is also a moving body]. Therefore, elliptical orbits are imaginary constructs, which may show relative positions of concerned bodies in space. They do not depict paths of these bodies in space. In reality there are neither elliptical orbits or foci for the central bodies to be in. Real orbital path of a planet is wavy about the path of its central body.

Details at http://vixra.org/abs/1008.0010

The calculation in this post assumes that the central mass is stationary, however in reality each body orbits the center of mass of the system, and both of those orbits are elliptical (with the center of mass in a focus).

For more than two bodies, and taking into account general relativity, you find that the orbits are only very, very, very nearly elliptical. The orbit of Mercury, due to general relativistic effects, shifts the farthest point in it’s orbit by about 1 degree every 8.5 thousand years (so it doesn’t quite close).

So, for an imaginary construct, it’s pretty good.

Pingback: Q: What is the three body problem? | Ask a Mathematician / Ask a Physicist

Elliptical orbits are perhaps due to the fact that the universe is expanding! Thus, the expanding movement imparts an excentricity to orbits that would have been circular if the universe were stationary!

Good basic point in that it is the expansion of our universe that imparts movement on large heavenly bodies, thereby causing eccentric movements of lesser heavenly bodies around these larger ones… makes sense? The only difference I see would be if there is no expansion of the universe, in which case there would be no significant movements (circular or eccentric) of bodies around their larger counterparts. In the sense of a retraction(collapse) of our universe… I would think that everything would then begin to operate in a reverse, perhaps even eccentric, order.

The expansion of the universe is important on really, really gargantuan scales. Even on the scale of a few million light years (the distance to the nearest galaxy) it’s negligible.

The elliptical-ness of orbits is purely a product of regular, dull as dishwater, Newtonian gravity.

There’s no mystery and no unknown causes behind elliptical orbits.

Thank you so much for the reply. I’m assuming then that the difference in mass between the orbital bodies, is somewhat responsible for the elliptical-ness effect powered by Newtonian gravity.

Nope!

Even if you have two equal-mass bodies they’ll still follow elliptical orbits. The only change is that, instead of the Sun being in one focus it’s the center of mass of both bodies. Technically, this is always the case, it’s just that when the Sun is involved the center of mass and the center of the Sun are almost the same.

Okay, so then an elliptical orbit is pretty much the norm.

What I now gather is that the Sun is not at the center of an elliptical orbit, but rather.. it is a little off to one side; at a point called a “focus” of the ellipse (just as you stated earlier). And it is because of this offset, that causes a planet to move closer to(perihelion) and further away(aphelion) from the Sun every orbit. Thanks for your time.

Veribion. What he said is that the Sun is not exactly at the focus, but orbiting it. The thing is that the focus is inside the Sun and very close to its center so its really jut waving a bit. This also means that we can approximate the Sun as being in the focus.

James, I feel the same a lot when I see derivations!

For the OP, I have a question: from step four to five, where you go from velocity dot force to derivative of energy, where has the negative sign go?

It got absorbed into the derivative of .

.

um so I don’t mean to seem disrespectful but I’m trying to understand this. I’m in year 10 at college at the moment and i was wondering if you could maybe try to explain it simply?

Back to the question about the sun being at one focus, but what is at the other focus? Years ago I was playing around with drawing ellipses with LOGO software (remember Turtle Graphics?), and I made an observation that I no longer have the mathematical skills to prove. As I watched the ellipse draw, with the center of the window at one focus, from 0 degrees to 90 degrees it drew the ellipse very slowly. Then from 90 degrees to 180 degrees, it traveled far to the left and got faster and faster. Then from 180 degrees to 270 degrees, it came back towards the center and drew slower and slower. Then finishing from 270 degrees to 360 degrees, it drew the last little bit of the ellipse slowly.

I realized that as the angle changed with a constant rate of change, sitting at the focus on the right, it traced out the path of the ellipse with what seemed to be the appropriate speed a planet would travel at as if the sun was at the focus off to the left. There is no physical object at this focus on the right, but rather the center of a polar coordinate system tracing the planet’s path. For any given time, the exact location of the planet can be calculated relative to this focus.

If this turns out to be true, and somebody out there can prove it to be true, and it wins that person some sort of physics/astronomy award, please reference this post and give me the credit as the inspiration for your computations. I can give my contact information if needed.

Thanks for the derivations! When you introduce the angular momentum L, do you use a unit mass (dimensional analysis of R²θ dot gives L²T⁻¹) ?

I was looking into this after my daughter asked why orbits are elliptical, and I couldn’t answer. I think that the simplest answer might be that they are elliptical because they can be. As you show above, an ellipse leads to a stable orbit, so it is possible. I think that the alternative that most people wonder about is “Why not a circle?” It seems that the only reason against a circle is that it is only one of an infinite number of possible ellipses (where f1=f2). So a circle could happen, but would be extremely unlikely since there are infinitely more other possible ellipses that are equally stable.

I believe orbits are elliptical because one of the two focuses is due to the resulting mass of the rest of the universe pulling the planet in that direction.

That is, the center of mass of the universe is in the direction from the sun to the other focus of the ellipse.

Not all orbits are elliptical, as well: there are parabolic orbits, hyperbolic orbits, and circular orbits.

One can see the shape of the four different orbital shapes by use of a conical dissect. Take a cone and slice it diagonally from one side to the other and you have the shape of an ellipse; slice it perpendicular to its longitudinal axis and you have a circular pattern; slice it at a sharper diagonal angle so the end of the cut exits the bottom of the base, but passing beyond the base center and you have the shape of a parabola; slice it at an even sharper angle to exit the base before crossing the center of the base and you have the shape of a hyperbola… these are know as the four shapes of a conic section.

An elliptical orbit will accelerate as it approaches perigee and decelerates as it nears apogee. On the other hand, circular orbits have no periapsis or apoapsis and therefore the orbit velocity remains constant.

To orbit Earth in a circular path the orbital path of satellites are positioned approximately 24,000 miles from the Earth’s center (dependent on the mass). Most communication satellites are positioned in a synchronous circular orbit around the equator in the same direction as the Earth’s rotation, but if the circular orbit is in reverse of the Earth’s rotation or in a polar orbit it would no longer be synchronous.

Moreover, due to changing gravitational forces, an orbital path is slightly irregular, this concept holds true for all four types of orbits, but more pronounced in a circular orbit not synchronous to the Earth’s rotation and due to the irregular shape of the Earth.

Furthermore, all elliptical and circular orbits are closed decaying loops and are eventually succumbed by gravity. Retro-rockets on satellites are used to occasionally reposition the satellite to sustain the orbital path for a longer period of time. Once the retro-rocket fuel is exhausted the satellite orbit can no longer be repositioned unless refueled while still in a sustainable orbital path; Skylab’s orbit for example decayed rapidly and crashed into Earth on July 11th, 1979.

Hyperbolic and parabolic orbits are open orbital paths that never return. These type orbits are used to send probes into outer space far away from Earth. Trajectories through space are always in a orbital curve and never in a straight line. To accelerate the velocity of an orbit, a slingshot method is used by directing the orbital path of an object towards a celestial body and using retro rockets with predetermined burn times to exit the trajectory path at the right moment and to enter into another orbital path with increased velocity.

What does our sun orbit?

there might be center of mass of whole solar system on the other focus

Pingback: Q: If the Sun pulls things directly toward it, then why does everything move in circles around it? | Ask a Mathematician / Ask a Physicist

How many foci would a circular orbits have

doing a course on satellite positioning but am still disturbed wth the question ‘what is at the other focus of the ellipse of earths orbit?’ keplerian laws only talk abt the sun as one focus of the ellipse.

It’s been a long time since i read bout this topic. Glad that i could be able to grasp the core of the argument.

Just wanna ask a few questions, if you can forgive my poor english (portuguese is my 1st language):

1) I noticed that you used L as angular momentum per unit mass, but you havent made any remark about that, is that so?

2) Soon after introducing S and alpha as new variables, how could you know that by defining S – alpha = sqrt(C + alpha²)cos(u) would yield a path to the solution?? I made the calculations at the paper and it worked, but damn, i cant help but to think that i would never be able to think about that change of variables!

3) Something similar ocurred to when you made the proof that the equation of R (theta) is describing an ellipse. It worked well, but its so frustrating to try to get at that by myself.

4) What about that D “phase”? You said that its just something not important, but i got curious about how its related to direction that the far side of the ellipse points at.

Thanks in advance for any help you and others could provide. Keep up the great work!!

@Gabriel Souza do Nascimento , which is then solved using cosines. Rather than use two substitutions, I just ran it all together. But really, this isn’t something you figure out; it’s something you vaguely remember from school and then you look up in the book you vaguely remember it being in.

, which is then solved using cosines. Rather than use two substitutions, I just ran it all together. But really, this isn’t something you figure out; it’s something you vaguely remember from school and then you look up in the book you vaguely remember it being in. , I saw once in something (maybe a book?) that was talking about orbital eccentricity. The first couple of attempts I made (that didn’t work) used (x,y) coordinates instead of (R,θ) coordinates.

, I saw once in something (maybe a book?) that was talking about orbital eccentricity. The first couple of attempts I made (that didn’t work) used (x,y) coordinates instead of (R,θ) coordinates.

1) That’s exactly right. In order for L to not be “per unit mass”, you’d have to keep the “m” from the first step. But that canceled out really nicely.

2) In the step before that there’s an integral of a constant over the root of a quadratic polynomial. That seemed familiar, so I flipped through an old book with some integral tables. Turns out; that happens a lot and the solution is to use trig functions. That weird substitution was all about trying to get something that looked like

3) That’s the nice thing about physics. The universe tells you the answer, so you don’t have to find the answer so much as find your way to the answer. If the math is right, and the laws are right, then all that’s left is algebra. That weird form,

4) The Earth’s orbit is elliptical with the long axis pointing in some direction. Whether that’s the x-direction or the y-direction or something in between is just something we (people) have to declare. That “D” shows up as a constant of integration, and it’s determined by which direction the ellipse points (according to our arbitrarily declared coordinate system).

Foci of an ellipse have always confused me. When I push a weight hanging on a string it will describe a straight line, a circle, or something in between-an ellipse. In all cases though the pattern will move around the center not one of the foci. I presume the orbital changes in gravitational attraction are the cause of the asymmetrical status of the two different foci. However if an object is placed in an elliptical orbit around the sun where the sun is at the center of the ellipse will it immediately transition into an orbital path where the sun is one of two foci or will the orbit remain stable?

I think its between the balance of Centripetal and Centrifugal force, When ever centripetal force( which is higher when the radius is short) crosses perigee of the ellipse, The Centrifugal force generated in that point and takes the earth to a longer distance up to apogee, and the centrifugal force degrades and comes to the Centripetal force pull towards the orbit.

I assume that the gravitational force of sun and centrifugal force will not be equal throughout the orbit of planets (perhaps due to disturbances of other planets or irregular shape of sun) so wherever the centrifugal force will dominate , the orbit will stretch out creating an ellipse. The reason for dominant centrifugal force can be gravitational force of other celestial objects attracting the planets in the direction away from sun. please tell me if I’m right or wrong!

@dev

The centrifugal force is greatest at the lowest point in an orbit, where a planet is moving the fastest, and least when a planet is at the highest point, where it is moving the slowest. So, it does change. However, other planets have only a very, very tiny effect on each other’s orbits. Even if there were exactly two bodies in the universe, they would orbit each other on elliptical paths.

Any old-fashioned gardener will tell you that all you need is a length of rope. Tap in two pegs (the foci), loop the rope slackly around them and then tauten it with another peg forming a triangle. (See diagram at start of page). Keep rope taut and move around marking the outline of your oval flower bed.

More seriously this use of bipolar coordinates stresses the fact that the sum of the distances from any point on the ellipse to the foci is constant. Moreover it easily shows that this distance is equal to the major axis.

Another nice way of showing this is to draw two sets of concentric circles with centres at

the two foci. Their overlap creates a series of points that satisfy the above criterion.

This arrangement will also show a set of hyperbolic paths and will be familiar to anyone familiar with GEE radar.

Kepler’s orbital laws are not correct.How the area law expression r*Vp=Ct may exist together with the period law expression r*Vp^2=Ct.Period expression is an observed fact.While area law expression is an estimation.When Newton’s Vp=Ct is proved ,r*Vp=Ct should be wrong.Then Kepler is wrong.To find Vp=Ct,use Newton’s universal attraction force.Say attraction force Fr is radial,a side force component Fp does not exist.So Fp=m*dVp/dt=0 means by integration Vp=Ct.Where is area formula r*Vp=Ct?

Some remarks on your wonderful analysis:

1. The first paragraph is simply the conservation of mechanical energy in a central force field: K+U=Const (multiply both sides by m and divide by 2).

Everyone should know that before attacking that issue.

2. The second paragraph, which is quite remarkable by itself, lacks some formalism. The angular momentum L (vector) = r (vector) x p (vector). |L|^2 (scalar) should have the mass of the planet embedded in the formula: |L|^2 = [m*R^2*theta(dot)]^2.

Thank you for that great work. I will use it – with your permission – in my classroom.

@Francis Zerbib

Thanks! You do hereby and forthwith have my permission.

Your answer is not the correct answer to my question.I am curious about Kepler’s celestial laws .Area law is r*Vp=Ct,Period law is r*Vp^2=Ct.How these two different argument may exist together in the same celestial physics? was my question. r*Vp^2=Ct is an observational fact not deniable.Then what means r*Vp=Ct.The angular momentum conservation has nothing to do with area law.And please do not change the notation .

I’m curious- if the sun’s mass were larger (or the earth’s smaller), would the distance between the sun and the other focus decrease and the orbit become closer to circular? I suppose that in essence, what I’m asking is if the eccentricity is a result of both the earth and the sun having mass.

My question is not “why orbits are elliptical”.My question is about Kepler’s area law r*Vp=Ct and also Kepler’s r*Vp^2=Ct.How these two arguments may exist together in the same physics,Either one is correct or the other.r*Vp^2=Ct is an observational fact ,not deniable.Then r*Vp=Ct is wrong and then Kepler’s elliptical orbit theory is wrong.Orbits should be spiraled according Newton’s attraction law.You will find Vp=Ct.And you must forget elliptical orbits.Please do not alternate my question.

@Necat

What are the quantities you’re using?

What do you mean by “quantities you are using”Quntities has not an effect ın my question.Is Kepler’s are law r*Vp=Ct correct or Kepler’s period law r*Vp^2=Ct correct?The period law is due to (r1/r2)^3=(P1/P2)^2,when P=2*pi*r/Vp and is also an observational fact. Undeniable.

@Necat

It sounds like you’re talking about Kepler’s second and third laws.

The second law says that the area swept out by a particular planet over a given time period is always the same (regardless of where the planet is in its orbit). This does not apply between different planets (the area swept out by different planets is different).

The third law says that all of the planets in the same solar system share a common ratio between the square of their orbital period and the cube of the length of their semi major axis (the long distance across the ellipse).

The second describes the behavior of a single planet at any time during its orbit. The third describes a commonality between all of the planets in a solar system. They’re talking about very different things.

Rigth! I am speaking of the second and third law of Kepler.The area law says r*Vp=Ct1

the period law says r*Vp^2=Ct2. I am asking how kepler’s r*Vp=Ct1 exist together with the period law r*Vp^2=Ct2.The period law (r1/r2)^3=(P1/P2)^2 is written r*Vp^2=Ct2 when we write P=2*pi*r/Vp. And now a little bit math: r*Vp^2/r*Vp=Vp=Ct2/Ct1=Ct3. Then Vp should be Constant.Kepler says Vp=variable.You can find Vp=Ct with Newton’s attraction law.So:F=Fr and a force component perpendicular to the radial does not exist.

F=Fp=0=m*dVp/dt means dVp/dt=0 and when integrated you find Vp=Ct.Kepler’s area law says Vp is variable along the orbit.Newton says Vp=Ct along the orbit.Which one is correct? That is my question for your confirmation.You are turning around my question but do not like to give a clear answer.You have to refuse Kepler’s laws.

@Necat

I think “Vp” is the tangential velocity, “r” is both the radius and the length of the semi-major axis, and “Ct” is a constant. Is that right?

“r” is what Kepler means:distance planet sun.”Ct” means constant. Vp is the perpendicular velocity to the radial velocity.As in Kepler,with vectorial notaton Vtangential=Vradial+Vperpendicular.(Vt=Vr+Vp).Kepler says r*Vp=Ct1 and also r*Vp^2=Ct2.Then r*Vp^2/r*Vp=Ct2/Ct1=Vp=Ct3 as discovered with Newton’s attraction force law.F=Fr=Fradial exist, F=Fp=perpendicular to the radial force component does not exist.That is Fp=m*dVp/dt=0=does not exist meaning by integration Vp=Perpendicular velocity to the radial is Constant3. Tangential velocity is a resultant vector. Vp is a component vector having a Ct3 scalar value as long as the body revolve around the attraction center. Vp direction may change,it does not matter.Scalar value is valid Kepler says Vp is variable,Newton says Vp is Ct3.Now is Vp constant or variable.That is the question.Very simple and clear.

@Necat

Newton and Kepler are both exactly right.

Newton says that the perpendicular velocity is constant in a circular orbit, but never in an elliptical orbit. Unfortunately, just because there is no perpendicular force does not mean that the perpendicular velocity stays the same. That sort of reasoning only applies in rectangular coordinates. Fp=0 doesn’t mean that Vp/dt=0.

It is exactly this difficulty that is addressed in the first block of math at the top of the post. A really good way to get around all of the coordinate transforms and head scratching is to use the conservation of angular momentum, which is just another way of stating Kepler’s 2nd law.

Where do you get rVp^2=Ct?

No!Newton and Kepler are not both exactly right. In any trajectory,when m*dVp/dt=0,we mean Vp=Ct.This is a Newtonian law.Either this law exist or does not exist.The trajectory may not be circular,but any shape when Fp=m*dVp/dt=0 it is obligatory to say Vp=Ct. Fp=0 means that dVp/dt=0.This is due to Fp=m*dVp/dt=0.This perpendicular velocity is innate and stays constant as scalar.The direction may change .The conservation of angular momentum is a wrong application to prove Kepler’s area law.But good to explain the kinetic inertia energy consevation I*w^2/2. Use the conservation of energy to discover what is the shape of the orbits.You will find the celestial motion equation r=-4*t^2+4*t*T-4*T^2/6. This equation is not an ellipse.But a parabola on Cartesian or a spiral on Polar.And r*Vp^2 is coming from the period law (r1/r2)^3=(P1/P2)^2 expression, when you write Period P=2*pi*r/Vp replacement.

@Necat (that is, the x component is 1 and the y component is t). There are no forces of any kind and the particle is traveling at a constant speed in a straight line. Expressing x and y using polar coordinates:

(that is, the x component is 1 and the y component is t). There are no forces of any kind and the particle is traveling at a constant speed in a straight line. Expressing x and y using polar coordinates:  and

and  . This means that

. This means that  . Differentiating with respect to time we get

. Differentiating with respect to time we get  and therefore (since

and therefore (since  )

)  which is decidedly not constant. There are no forces, and yet an object that passes by in a straight line has continuously varying perpendicular velocity.

which is decidedly not constant. There are no forces, and yet an object that passes by in a straight line has continuously varying perpendicular velocity.

A zero perpendicular force does not, and this is important, does not mean that the perpendicular velocity is constant. Imagine a particle traveling in a straight line parameterized by

This sort of thing happens all the time. Cylindrical coordinates are tricky.

Or ignore all of that and just imagine a car passing by on the highway; it’s in the same direction for a long time, then you suddenly have to turn your head (because their perpendicular velocity jumps).

Sorry! I don’t think you comment about physics but about similar triangles geometry .When a particle is traveling with a tangential velocity Vt in a straigth line the radial distance (r) to the particle and the perpendicular line distance (d) to the straigth line are written d/r=Vp/Vt.that is r*Vp=d*Vt.When d and Vt, are chosen constant r*Vp=Ct looks to be proved,even the angle (theta)between the straigth line and (r) is variable.Then Vp=Vt*sin(theta) will be not constant as (theta) is changing.But these are not Newton’s or Kepler’s law.These are classic geometrical law.And the orbit is not a straigth line.Also Vt is a resultant vector. Vp is a component vector.To think

Vp=Vt*sin(theta) is not the proving case.But Vt=Vp/sin(theta) is our case.These are different thinkings. One gives variable Vp as you try to prove,the other gives variable Vt as (theta) varies.Give me your mail address,I may send you a graph of this math.

I think you try to confuse my mind with variable notation.

@necat

“ask a mathematician” (all one word) at gmail.