Quick aside: “Zeno’s paradox” was originally proposed (probably) by Zeno, who was basically trying to show that movement is impossible. His idea was that in order to get to where you’re going you need to cover half of the distance, then half of what remains (1/4), then half of what remains (1/8), and so on. So you’re covering an infinite number of half-ways, which just can’t be done since there’s an infinity in there. Mathematicians today ain’t shook, firstly because there aren’t any actual problems with the math and secondly because they can move to their chalk boards to check.

The “Quantum Zeno effect” or “Turing Paradox” is the idea that if you measure a quantum system repeatedly and rapidly you can prevent it from changing. Kind of “a watched quantum pot never boils” sort of thing. This is yet another example of the math behind quantum theory writing checks that nobody though the experiments would be able to cash. And yet…

Physicist: It is a real effect!

However, it’s not like if you pay attention to a uranium brick it becomes less radioactive and if you look away it becomes more radioactive. The details depend on how you do the measurement, and (it’s worth mentioning) not on whether or not a conscious Human being is doing the measuring.

As always, the easiest thing to consider is light, which wears its quantum mechanical properties like they’re going out of fashion. There are a lot of things that cause the polarization of light to rotate, like passing it through sugar water. Just by measuring the polarization rapidly you can actually halt (or nearly halt) the rotation.

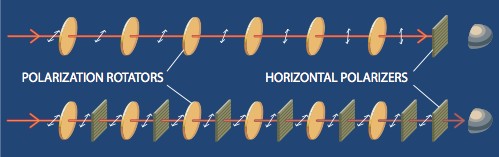

Horizontally polarized light that passes through a series of “rotators” will eventually become vertically polarized and won’t pass through a horizontal polarizer. However, repeated measurements can prevent that from happening, despite the fact that the measurements aren’t really affecting the light.

“Measure” in this case means “pass the light through a polarizer“: if it passes through it has the same polarization as the polarizer, and if it doesn’t pass through then it didn’t have the same polarization. The greater the difference in angle between the polarization of the light and the polarization of the polarizer, the lower the chance that the light will get through, until at 90° none of the light gets through.

Classically (“classical” means “before quantum mechanics”) the interaction that we see between a polorized photon and a polarizer is impossible. It should be that if you have a vertically polarized photon and it tries to pass through a horizontal polarizer, at any time, it’ll be stopped. A bunch of do-nothing measurements shouldn’t change that. In the example above, the rotators should make it so that with each rotator the chance of the photon getting through the next horizontal polarizer gets smaller and smaller.

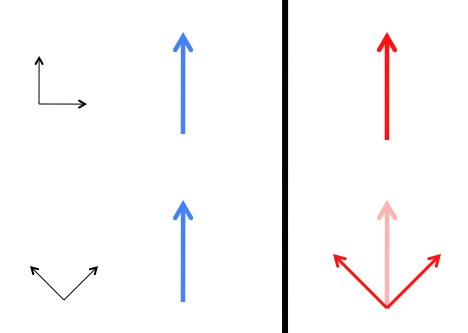

But the quantum mechanical nature of measurements is different and very weird. If light passes through a polarizer it comes out having the same polarization as the polarizer, without actually changing or being affected by the polarizer (this is where the weirdness of quantum mechanics comes in). A classical photon (or a classical anything) needs to be in one particular state. But in quantum mech, as demonstrated by the Stern-Gerlach experiment (among others), even when you know that a photon is polarized in one particular direction, it’s still in multiple states. It’s just a matter of picking a “basis”. For example, a vertical state is combination of the two diagonal states.

The state of a classical photon is what it is, regardless of how you measure it (blue). But the state of a quantum photon (actual photon) takes different forms depending on how it’s being measured. In this particular case, a vertical state is exactly the same as a combination of diagonal states (red).

Not only can you halt the change of a quantum system through measurement, you can induce change. For example, you can rotate the polarization of light by measuring it a few times.

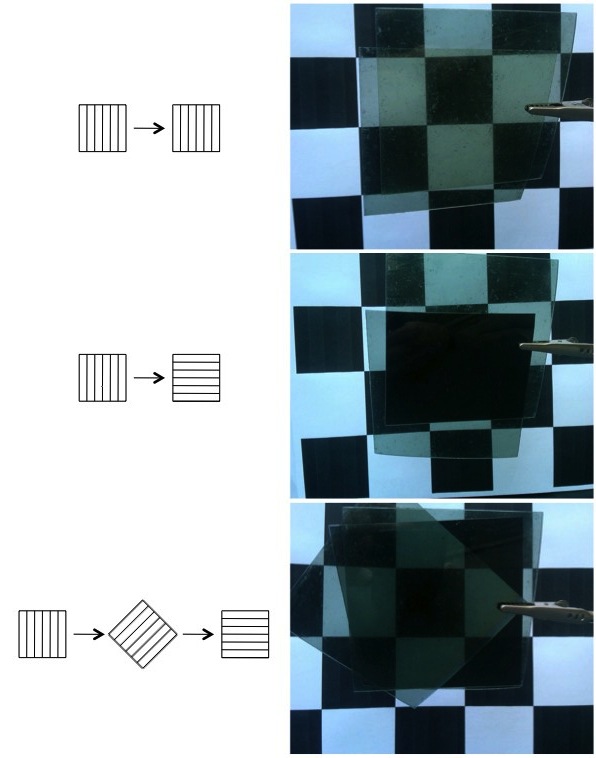

If you shoot vertically-polarized light at a horizontal polarizer, nothing will get through (there’s no in

). But if you shoot it at a diagonal polarizer first, half will get through the diagonal polarizer (

is half

and half

), and then half of that will get through the horizontal polarizer (

is half

and half

). Just by measuring the polarization, some of the light has been changed from vertical to horizontal! (the rest is destroyed)

Normally light can’t travel through a vertical polarizer and then a horizontal polarizer. But by putting a diagonal polarizer in between them, suddenly it’s possible (about 1/8 of the ambient light gets through all three). This “measurement effect” is impossible in classical physics.

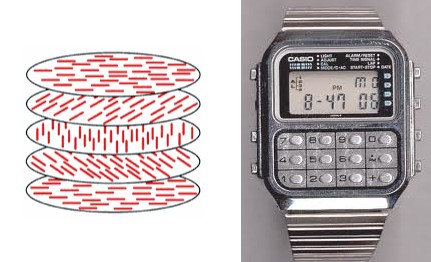

By replacing the single 45° intermediate polarizer with a fan of dozens of polarizers you can get almost all of the light through and rotate the polarization as much as you like. In fact, this is the essential idea behind how most polarization rotators work. For example, in the face of a digital watch, or in every pixel of an LCD screen, there’s a layer of liquid crystal that twists when an electrical voltage is passed through it. It goes from acting like a series of vertical polarizers, to acting like a fan that can rotate light. In this way it can rotate the polarization of the light to either pass through or be stopped by a stationary polatizer, which is generally the outer-most surface of the screen.

Answer gravy: The probability that a photon of one polarization will pass through a polarizer that’s offset by some angle θ is P = |cos(θ)|2. So for example, if the polarization of a photon is vertical and the polarizer is set at 45°, then there’s a 50% chance of the photon going through: P = |cos(45°)|2 = |1/√2|2 = 1/2. Once the photon goes through it assumes the polarizer’s angle of polarization.

Technically, this is a result of the polarizer removing the part of the photon’s probability amplitude that’s perpendicular to the polarizer. Literally, the photon both does and doesn’t go through the polarizer, and the part that goes through is the part that “agrees” with the polarizer.

If you have a fan of N polarizers separated from each other by θ, then the probability of a photon making it through all of them is P = (|cos(θ)|2)N = |cos(θ)|2N. So, let’s say you want to get a bunch of photons to end up rotated by 90° (π/2 radians) by passing it through N polarizers, each offset from the one before by θ = 90°/N = π/(2N): P = |cos(π/(2N))|2N. But check this out!

The second term there gets real small, fairly fast, so by adding more and more polarizers at smaller and smaller angles, the chance of a photon getting all the way through can get arbitrarily close to 100%. For example, 90 polarizers that each shift by 1° allow over 97% of the light to get through.

In classical physics (where light can only be in one definite state), you’d expect very nearly zero light to get through, because in that fan of 90 polarizers, some of them will be perpendicular or nearly perpendicular to any given photon that comes along.

The cat picture from is from here.

The professional looking polarizer picture was taken from this article.

Oho that watch thing is clever, i never realised that was how they work.

Could you explain why |1-(π^2)/(8N^2)|^2N ≥ |1|^2N-|(π^2)/(8N^2)|^2N ?

I don’t understand, why you are allowed to split the 2N power onto the two terms…

I was misusing the triangle inequality on purpose, as a joke. It was terribly clever.

I’ll fix it!

i have never heard of this.I’ll try making one

this is good.wow

I should probably stop staring at my uranium brick to make it last longer, shouldn’t I?

How do we know that -Sin(x)^2 > x^2 ? I know -x^2 is going to keep getting smaller and smaller while -Sin(x)^2 will oscillate between 0 and 1, but how do you actually show that inequality is true?

In the 3-polarizer demonstration, isn’t it just as plausible that the diagonal polarizer is simply diffusing the light (the plastic substrate that the polarizer is made of not a perfect mathematical construct and is composed of a pretty thick chunk of atoms and molecules I would expect) thus refracting/depolarizing 12.5% of the light (via internal reflections perhaps?) into a different rotation which would then pass through all sheets?

Can someone explain how it is known that is not what’s happening?

Thanks!

@Ven Burbank

If each polarizer scattered the incoming light into random nearby polarizations, then a stack of identically aligned polorizers would be almost opaque. Light that has passed through a vertical polarizer has a 100% chance of passing through a subsequent vertical polarizer, but if each one randomized the polarization a little, then less than 100% would pass through the next and the next and the next…

But this isn’t the case. More importantly, this is just one example of a larger and more all encompassing theory. The same ideas hold true for the spin of electrons, or photons taking multiple paths, or really any non-trivial quantum system. The one presented here is just one of the easier ones to understand (and take crappy pictures of).

Quantum zeno effect could mean there is no God or at least there is no God who watch all the time?

I was going to give a presentation at American Physical Society in March that got cancelled. It discusses the mechanism of quantum mechanics and relates observer reset, not observation to multiple effects, including the Zeno effect. It is a 10 minute presentation:

Did it occur to anyone that multiple instances of decoherence/measurement in the path of a particle causes the particle to go back into superposition? We see this in which-way eraser experiments. A wave in superposition doesn’t care about polarization. The zeno effect is dead.