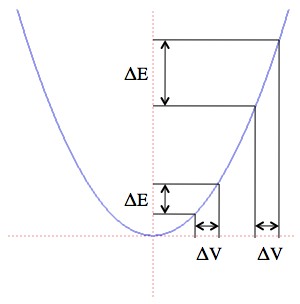

Physicist: When a rocket fires it increases its speed by some fixed amount called the “ΔV” (delta V). If the original speed is W, and the rocket speeds up by ΔV, then the change in energy is: . So here’s the problem; notice that the increase is not just

, but is instead bigger when the initial velocity is bigger. Isn’t that weird?

Kinetic energy vs. Speed: The change in energy is different for different starting speeds even if the change in speed is the same.

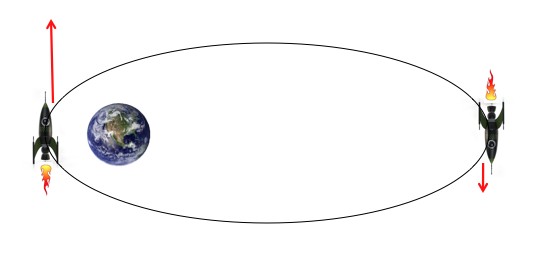

This comes up a lot when you’re shooting rockets around the solar system. If the rocket has a big elliptical orbit, then it’ll be moving quickly at the closest part of the orbit and slowly at the highest part of its orbit (just to be confusing, these points are called the “periapsis” and “apoapsis”). So, very weirdly, if the rocket fires when it’s moving the fastest it’ll pick up more more kinetic energy and it’ll be able to get higher and farther. But if the rocket fires when it’s moving slowly it gains less energy, and at the most extreme, if W = -ΔV/2, then the energy doesn’t change at all (the rocket just switches direction). This is a basic rule of thumb in rocket science; if you’re going to fire your rocket, fire it at the lowest point in its orbit. But the question remains: Wha…? Why?

At different parts of an orbit the same amount of fuel translates into different amounts of kinetic energy. This “Oberth effect” comes about because the ship travels at different speeds at different points in the orbit.

The very short answer is that you need to take into account what the exhaust is doing as well as what the rocket is doing. We usually think of a rocket as a thing that propels itself through space. In fact, it’s better to think of a rocket as a “gas cannon” that throws as much stuff as possible, as fast as possible, out of its more interesting end.

Rockets and cannons both throw stuff as fast as they can. The only real difference is that a cannon is nailed down.

When the rocket is slow the exhaust travels quickly and carries away a lot of kinetic energy. When the rocket is fast the exhaust is closer to sitting still (in fact, if the rocket is already traveling at the exhaust velocity, the exhaust is basically dropped off). Overall, energy is always conserved (it’s practically a law), it’s just a question of how much goes into the rocket, where it’s useful, and how much goes into the exhaust, where it’s not.

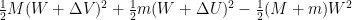

So check it! Imagine that a parcel of fuel with mass m gets burned and ejected at a speed of ΔU. Conservation of momentum says that the momentum of the rocket and fuel before burning is the same as the momentum afterward. Mathematically, this is MΔV + mΔU = 0. The energy before the burn is and the energy afterward, from the rocket and the fuel parcel, is

. The change in energy is

Huzzah! This is exactly what you’d expect; when you take into account all of the stuff that’s flying around, all of the weirdnesses disappear. The dependence on the initial speed is gone, and you’re left with the same gain in energy you’d see from a rocket starting from a stand-still. So the Oberth effect, which seems like a violation of the conservation of energy at different speeds, is just a failure to take into account that a rocket slings fuel. Rather than being a magical extra boost when a rocket is traveling fast, it’s just a cute and fortunate distribution of energy.

Thanks for this explanation. I wonder whether the question was asked by a Kerbal gamer… 🙂

I still do not understand one thing : if some fuel is burning, should not both the rocket and the exhaust gaz be equally ‘pushed’ by the reaction, whatever the rocket+fuel speed is? Said differently, even if I understand that the exhaust gaz would appear to be dropped of from an immobile point of view, as the fuel has the same speed as the rocket, then the burn reaction is the same relatively to the rocket, so how its velocity could ‘push more’ the rocket at high speed?

And this is why we can’t have reaction less drives. It breaks relativity.

Sorry to necro this, but I cannot for the life of me understand why in the second line:

…1/2*mW^2 + mWdU + 1/2 * mdU^2…. isn’t:

… 1/2*mW^2 – mWdU + 1/2 * mdU^2…

Am I doing something wrong? i always thought (x-a)^2 was x^2-2ax+a^2.

this changes the end answer to 2MWdV + 1/2*MdV^2 + 1/2*mdU^2.

What am I missing?

@Travis and not (as you caught)

and not (as you caught)  . I got it in my head that since the exhaust and rocket are going in different directions one should have a negative sign. But it shouldn’t.

. I got it in my head that since the exhaust and rocket are going in different directions one should have a negative sign. But it shouldn’t.

Thank you so much for catching that! You are absolutely and totally right. My mistake was in the first line, which should read

What happens to Potential Energy? When rocket is moving upward, is P.E is constantly increasing.So its K.E must decrease to conserve energy but it is increasing?Why?

Pingback: Q: Why does kinetic energy increase as velocity squared? | Ask a Mathematician / Ask a Physicist

I don’t understand. The rocket and the exhaust are not aware of the velocity they are traveling (compared to what). Somehow firing the rocket at its fastest velocity must propel it faster relative to something. The rocket will always be traveling fast compared to something else and slow compared to another thing. This idea of the exhaust coming out at the speed the rocket is going and putting more of the energy into the rocket does not seem logical.

@Travis you were right and @The Physicist you got it wrong after getting it right the first time (you can’t have same sign for two velocities in opposite direction while adding them) because of your own basic (and silly) mistake which is your conclusion,

that, MdV + mdU = 0

You derived it wrong (it shows that both of them have to be zero all the time). It is in fact,

MdV – mdU = 0

from conservation of linear momentum,

(M + m)W = M(W + dV) + m(W – dU)

MW + mW = MW + MdV + mW – mdU

0 = MdV – mdU => MdV = MdU

so it is,

dU = (M/m) dV

not that what’s you substituted wrongly,

dU = – (M/m) dV.

Now you can have the right equation for energy change (combined rocket and fuel parcel) that you messed with trying to correct your mistake (the silly one).

dE = (1/2) M(W + dV)^2 + (1/2) m(W – dU)^2 – (1/2) (M + m)W^2

Note the negative sign for dU in (W – dU), it will lead to,

dE = (1/2) M(dV)^2 + (1/2) m(dU)^2.

The same result you wanted.

Fancy math aside (I never took a calc class), is the way you would explain this using plain English as, “this is why when rockets are launched into space, they burn for a few seconds before taking off so the rocket is technically already at the lowest point in its orbit”? Or am I still really confused?

Charles, the problem that you cite seems logical at first, except for the fact the the initial AND final velocities are both with respect to a certain point (the object being orbited). The equations could be solved using any point of reference, so long as it is inertial, and yield the same effect. This excludes using the rocket or exhaust as a reference frame, because the whole point of the theory is to determine the change of momentum for both the rocket and exhaust.

whether the oberth effect is suitable in air condition?

I don’t understand, the initial problem posed has nothing to do with rockets or exhaust:

“the change in energy is: 1/2 M(W+ΔV)^2 – 1/2 MW^2 = 1/2 M(ΔV)^2 + MWΔV. So here’s the problem; notice that the increase is not just 1/2M(ΔV)^2, but is instead bigger when the initial velocity is bigger. Isn’t that weird?”

This effect would be the same if we were measuring a hamster running along in a hamster wheel, or a baseball thrown with some initial velocity W and then accelerated by a gust of wind, or any other accelerating object. Explaining this in terms of rocket exhaust isn’t really satisfying. I still don’t understand where the extra energy comes from, fundamentally.

@Scott , the extra energy for a rocket is basically taken from Earth’s speed(Or any other body which the rocket uses to propel itself). Since the speed of the earth is massive(also relative) the change in it’s speed is neglible. The inital velocity will be bigger, if its closer to the periapsis of Earth (Kepler’s law) and less if it is farther away.

I hope your question is answered

“When the rocket is slow the exhaust travels quickly and carries away a lot of kinetic energy. When the rocket is fast the exhaust is closer to sitting still (in fact, if the rocket is already traveling at the exhaust velocity, the exhaust is basically dropped off).”

This is incorrect. The speed at which the exhaust exits the rocket with respect to the rocket is independent of the speed of the spacecraft.

In fact, the exhaust is a red herring. A velocity change from any source – such as a solar sail – will have a greater effect on an object’s energy if the object is moving faster.

@Nick

The reference frame is clearly the body being orbited (Earth). In this reference frame, the gas particles are dropped off. Of course they are not dropped off relative to the rocket though.

But you are right; if a constant force is applied to an object over a specific time interval, then a faster moving object will always acquire more energy since it is moving through a larger distance. Work = Force * Distance

I always assumed , when I heard about the Oberth Effect, that the main cause of it is because the Kinetic Energy is calculated by square Velocity , exponentially. So, in a Vaccum without any drag, while spending the same ammount of fuel mass to speed up by 10 units, you get way more Kinetic Energy when you add up those 10 Units to a higher base value.

10×10=100 and 20×20=400 (+300)

1000×1000=1 000 000 , BUT 1010×1010=1 020 100 (+20 100).

Correct me if I am wrong , but isn’t it the only reason? You build up more Kinetic Energy by going faster since it is squared. If it was cubic (in other words, even more exponentially), Oberth Effect would be even more useful.

On some other matter, exhaust speed is usually capped at Mach 1 whereas an orbital rocket is at around Mach 20. Even so, the fuel it carries is also at Mach 20 so you can’t really say the Exhaust is at a stand still compared to it. Compared to the referential it is RocketSpeed+ExhaustVelocity, while compared to the rocket it is RocketSpeed+ExhaustVelocity-(RocketSpeed). So, as obvious, it does provide thrust because it is moving faster and pushes the rocket on the opposite direction as Newton said! Am i saying BS?

Joseph has the best answer though I still don’t understand properly. There must be some kind of relativity thing going on.

What happens if the rocket is in open space away from a planet/star/galaxy and what if it is an ion drive?

@Dafydd

Exactly right: this is a relativity thing. From the rocket’s point of view, it doesn’t matter when it fires, the increase in velocity is always the same. But a differently moving observers can disagree about what the initial and final velocities of the rocket and exhaust are, and that means they can disagree on how much kinetic energy they each have.

Ion drives don’t change the situation (other than making it sound a little more futuristic).

If you launched a rocket from a static position at 128,000 feet, would it be almost as inefficient as launching it at sea level, to an extent, because the exhaust is moving faster than the rocket? Would it be better to let the rocket fall to approximately terminal velocity, then fire the rocket and adjust the trajectory to climb again?

There is a lot of math being thrown around in this discussion, but it really comes down to basic algebra: (a+b)² = a² + 2ab + b² [ Note that it’s not: (a+b)² = a² + b² ]

It’s the 2ab term that creates the Oberth effect.

KE = 1/2 Mass * (Velocity)²

If if a rocket burns for a certain amount of time, it will impart a change in velocity (ΔV). If your original velocity is V, your new velocity is V+ΔV. Since KE is proportional to velocity squared [ KE α (V+ΔV)² = V² + 2*V*ΔV + ΔV² ]

your change in KE is then proportional to 2*V*ΔV + ΔV² [= (V² + 2*V*ΔV + ΔV²) – V² ]

Therefore, the greater the initial V is, the greater the change in V for a given ΔV from thrust.

It may be a little hard for earth-bound folk to comprehend this intuitively, because we are used to decelerating into a turn, and accelerating out of it (applying thrust at the point of lowest velocity), but that has everything to do with not exceeding the maximum grip force of our tires, and understanding, possibly intuitively, that the lateral force vector must be added to any longitudinal force vector (forward acceleration or braking).

The oberth effect is useful when considering orbital maneuvers, you get a greater increase in apoapsis from a given delta v burn when it’s at a lower periapsis, thats it.

The rest of the discussion is pointless.

@Anonymous Understanding the underlying physics of a natural phenomenon is “pointless”? Interesting point of view. Good thing great physicists like Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein did not share this point of view, or we’d still be riding around in horse buggies, burning witches, cutting holes in people’s heads to “release the evil spirits” and believing that the Earth was flat. What fun!

Thank you this helped me understand what’s really going on!

Could you also see this as the central body accelerates the fuel, then it is ejected and so the mass being decelerated on exit is smaller than the mass that was accelerated?

In short, the gravity adds KE to the fuel speeding it up, it is ejected and then the fuel is not on board to be “slowed down” on exit from the well.

The original statement heads the discussion off on a tangent:

“the change in energy is: 1/2 M(W+ΔV)^2 – 1/2 MW^2 = 1/2 M(ΔV)^2 + MWΔV. So here’s the problem; notice that the increase is not just 1/2M(ΔV)^2, but is instead bigger when the initial velocity is bigger. Isn’t that weird?”

Its not at all weird. The derivative of energy with respect to velocity is the MW term. The ΔV^2 can be ignored. The idea is that a reaction engine adds a certain delta V regardless of what speed it is travelling at. If that speed is higher, the resulting kinetic energy is higher.

if the rocket is going at 4m/s, and the rockets increase its speed to 5m/s we go from 0.5M(16) to 0.5M(25).

if the rocket is going at 8m/s we move to 9m/s and the kinetic energy moves from 0.5M(64) to 0.5M(91). Which is a greater increase in energy.

We don’t need to consider relativity or which frame of reference. If the rocket is moving faster, a fixed delta V leads to a greater increase leads to a greater increase in kinetic energy – because the rocket it moving faster.

That’s all that’s happening.

@conor

Its weird because you still burn same amount of fuel in a same amount of time, so constant energy is produced by fuel, but rocket receives every unit of time more and more and more energy. Where do this energy come from?

Final equation tells us in fact that steel body rocket receives constant amount of energy.

MATH-FREE EXPLANATION: The chemical energy of the burnt fuel (minus thermal losses) is converted into kinetic energy changes of both the rocket AND THE EJECTED GASES. If the rocket (and the fuel) is motionless or moves only slowly at the start, then both rocket and ejected gases GAIN kinetic energy. The kinetic energy produced is therefore distributed between the two.

When the rocket moves at a speed higher than the ejection speed of the hot gases, then the ejected gases don’t actually move backward relative to a fixed frame of reference. They continue to move forward but at a reduced speed (equal to the initial rocket speed minus the ejection speed). Therefore they actually lose some kinetic energy. By virtue of energy conservation, this “lost” kinetic energy must go to the rocket. Thus the rocket gains more energy from the burn than if it had started from rest.

By interpolating and extrapolating from these two cases you can see that the Oberth effect works at all velocities.