Physicist: Here’s every particle you’ve ever interacted with: protons, neutrons, electrons, and photons*. Dangerous radiation is nothing more mysterious than one of those particles moving crazy fast.

The nucleus of some kinds of atoms are unstable and will, given enough time, re-shuffle and settle into a lower-energy, more stable form. The instability comes from an imbalance in the number of neutrons vs. protons.

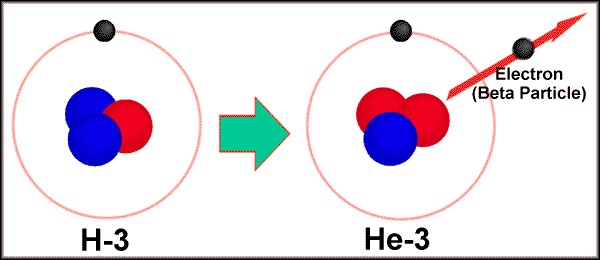

The most common forms of “radioactive decay” are beta+ and beta-, and these happen because a nucleus has either too many protons or too many neutrons. Beta- is a neutron turning into a proton, an electron, and some extra energy. Beta+ is a proton turning into a neutron, an anti-electron, and some extra energy. The protons and neutrons stay in the nucleus, and the new electron or anti-electron takes most of that new energy and flies away. That fast electron or anti-electron is the radiation.

Tritium is a type of radioactive hydrogen that has one proton and two neutrons. Occasionally, one of those neutrons will “pop” and turn into another proton and an electron. The result is a helium-3 atom, and a really fast electron.

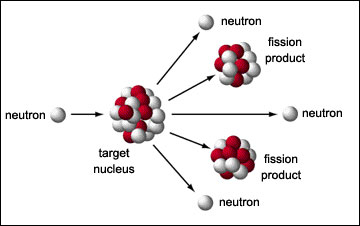

Sometimes a neutron is ejected (neutron radiation), usually when the entire nucleus breaks apart (which is nuclear fission). Neutron radiation is exciting for physicists because neutrons are nice, no-fuss particles. Without a charge, neutrons are about as close to atomic bullets as you can get.

The most common source of neutron radiation is fission, which generally spits out a few extra neutrons. This picture is of a controlled reaction (activated by a nearby neutron source).

Finally, an “alpha particle” is sometimes ejected. Alpha particles are a pair of protons, and a pair of neutrons, that are stuck together. This is the same as a helium nucleus, so this is basically “high-speed-helium”. “Alpha decay” is why there’s helium on Earth. The helium that was around during the Earth’s formation found it’s way to the top of the atmosphere, and from there was knocked into space by solar radiation and wind. Unlike hydrogen, which can bond to things chemically (the “H” in “H2O”), helium is a noble gas and doesn’t stick to anything. All the helium that slowly bubbles out of the ground is from the radioactive decay of heavier elements inside of the Earth. So, when you fill a balloon with helium, you’re literally filling it with what used to be radiation. Fun fact: that slow dribble of helium doesn’t amount to much, and we’re about to run out.

The most common and dangerous kind of radiation is high-frequency light. High-energy light is called “x-rays” and above that “gamma-rays”, and it tends to punch through shielding a lot better than the other kinds of radiation (that’s why x-rays can be used to look through things). Alpha, beta, and neutron radiation are made of matter and they tend to bump into things and slow down. A couple pieces of paper do a pretty decent job stopping alpha particles, and a few inches of water stop neutron and beta radiation remarkably well. Gamma rays, on the other hand, are what lead shielding is for.

Radiation is dangerous because it can ionize, which breaks apart chemical bonds. If that happens enough inside a living cell, then the cell will be killed. With enough broken chemical “parts” they just stop working. “Radiation poisoning” is what happens when you’ve suddenly got way too many dead cells in your body, and too many of the cells that remain are too damaged to reproduce.

When you get a sun burn you’re suffering from a little radiation damage. UV light has enough of a punch to kill cells, which is a big part of why our outer layers of skin are just a bunch of dead skin cells: radiating dead cells doesn’t do much, so the body keeps them around to protect the living layers underneath. This is also why really tiny bugs don’t like direct sunlight (they’re smaller than the protective layer they would need).

For those of you worried about radiation: wear sunscreen. You’re far more likely to be harmed by chemical pollutants. Other forms of light, like radiowaves, microwaves, or even visible light, don’t have enough power in each photon to ionize. As a result, all they do is heat things up (not blast them apart). In order for your cell phone to do any damage to you it would have to literally cook your head, as in “increase the temperature until such time as you are dead”. In that respect, a warm room is far more “dangerous”.

Every living thing on the planet has developed at least some ability to deal with low-level radiation, which is unavoidable (some are ridiculously good at dealing with it). Each cell in your body has error correcting mechanisms that deal with genetic damage (DNA blown apart by ionizing radiation), and even when a small fraction of your cells die: no problem. They’re just put in the bloodstream, filtered out, and poo’d. As it happens, dead red blood cells are a major contributor to the color of poo! Chances are you’ll remember that particular and unappetizing fact forever, so… sorry.

You’re struck by about 1 particle of ionizing radiation per square cm per second. More at high altitudes, and more during the day. By far, the most dangerous source of radiation that you’re likely to come across (outside of a hospital), is the Sun. Luckily, the Sun is easy to spot, and easy to avoid. Shade and sunscreen. Easy.

The beta particle picture is from here, the fission picture is from here, and the radiator picture is from here.

*There are other particles beyond those four, such as gluons or W bosons or even higgs bosons, that show up all the time. But, they’re kinda “behind-the-scenes” particles that only show up for insignificant fractions of a second and are virtual. If you find yourself in a situation where you’re interacting with these rarer particles, then you probably work at CERN and should know better.

Pingback: Machine Envy: Science is Becoming a Cult of Hi-Tech Instruments | pundit from another planet

What makes non-ionizing radiation dangerous? Does it just knock into molecules enough to damage them, or are there any secondary effects?

Non-ionizing radiation can pass enough energy to cause structural changes to proteins within cells. The protein molecule isn’t directly damaged, but the shape of the protein, which is essential for how it functions, is changed. This prevents the proteins from performing their role properly e.g. cause miscoding of DNA resulting in mutations which lead to cancer.

If the half life of uranium isn’t longer than 4.5 billion years,how is it not all turned to lead by now?

Hi; I worked with Isotopes many years ago, i was always very respectful, especially when you noticed the lead screening starting to evaporate, after only a few weeks. Thank goodness for my little blue badge. We were testing tank track, for the MOD at the time. Looking for tiny gas bubbles in 50mm thick castings, i have no idea what the metal was, but it was very light ! Happy Days.

Pingback: Radyoaktif maddeler nasıl oluşur | Düşünbil Portal - Düşünmek Özgürlüktür!