Physicist: When you’re doing math with numbers that aren’t known exactly, it’s necessary to keep track of both the number itself and the amount of error that number carries. Sometimes this is made very explicit. You may for example see something like “3.2 ± 0.08”. This means : “the value is around 3.2, but don’t be surprised if it’s as high as 3.28 or as low as 3.12… but farther out than that would be mildly surprising.”

However! Dealing with two numbers is immoral and inescapably tedious. So, humanity’s mightiest accountants came up with a short hand: stop writing the number when it becomes pointless. It’s a decent system. Significant digits are why driving directions don’t say things like “drive 8.13395942652 miles, then make a slight right”. Rather than writing a number with its error, just stop writing the number at the digit where noises and errors and lack of damn-giving are big enough to change the next digit. The value of the number and the error in one number. Short.

The important thing to remember about sig figs is that they are an imprecise but typically “good enough” way to deal with errors in basic arithmetic. They’re not an exact science, and are more at home in the “rules of punctuation” schema than they are in the toolbox of a rigorous scientist. When a number suddenly stops without warning, the assumption that the reader is supposed to make is “somebody rounded this off”. When a number is rounded off, the error is at least half of the last digit. For example, 40.950 and 41.04998 both end up being rounded to the same number, and both are reasonable possible values of “41.0” or “41±0.05”.

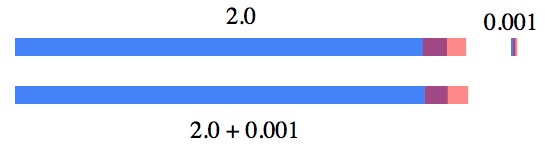

For example, using significant figures, 2.0 + 0.001 = 2.0. What the equation is really saying is that the error on that 2.0 is around ±0.05 (the “true” number will probably round out to 2.0). That error alone is bigger than the entire second number, never mind what its error is (it’s around ±0.0005). So the sum 2.0 + 0.001 = 2.0, because both sides of the equation are equal to 2 + “an error of around 0.05 or less, give or take”.

2.0 + 0.001 = 2.0. The significant digits are conveying a notion of “error”, and the second number is being “drowned out” by the error in the first.

“Rounding off” does a terrible violence to math. Now the error, rather than being a respectable standard deviation that was painstakingly and precisely derived from multiple trials and tabulations, is instead an order-of-magnitude stab in the dark.

The rules regarding error (answer gravy below) show that if your error is only known to within an order of magnitude (where a power of ten describes its size), then when you’re done adding or multiplying two numbers together, what results will have an error of the same magnitude in the sense that you’ll retain the same number of significant digits.

For example,

This last expression could be anywhere from 3.8988 x 102 to 3.9988 x 102. The only digits that aren’t being completely swamped by the error are “3.9”. So the final “correct” answer is “3.9 x 102“. Not coincidentally, this has two significant digits, just like “0.32” which had the least number of significant digits at the start of the calculation. The bulk of the error in the end came from “±1.234×0.05”, the size of which was dictated by that “0.05”, which was the error from “0.32”.

Notice that in the second to last step it was callously declared that “0.0617 ≈ 0.05”. Normally this would be a travesty, but significant figures are the mathematical equivalent of “you know, give or take or whatever”. Rounding off means that we’re ignoring the true error and replacing it with the closest power of ten. That is, there’s a lot of error in how big the error is. When you’re already introducing errors by replacing numbers like 68, 337, and 145 with “100” (the nearest power of ten), “0.0617 ≈ 0.05” doesn’t seem so bad. The initial error was on the order of 1 part in 10, and the final error was likewise on the order of 1 part in 10. Give or take. This is the secret beauty of sig figs and scientific notation; they quietly retain the “part in ten to the ___” error.

That said, sig figs are kind of a train wreck. They are not a good way to accurately keep track of errors. What they do is save people a little effort, manage errors and fudges in a could-be-worse kind of way, and instill a deep sense of fatalism. Significant figures underscore at every turn the limits either of human expertise or concern.

By far the most common use of sig figs is in grading. When a student returns an exam with something like “I have calculated the mass of the Earth to be 5.97366729297353452283 x 1024 kg”, the grader knows immediately that the student doesn’t grok significant figures (the correct answer is “the Earth’s mass is 6 x 1024 kg, why all the worry?”). With that in mind, the grader is now a step closer to making up a grade. The student, for their part, could have saved some paper.

Answer Gravy: You can think of a number with an error as being a “random variable“. Like rolling dice (a decidedly random event that generates a definitively random variable), things like measuring, estimating, or rounding create random numbers within a certain range. The better the measurement (or whatever it is that generates the number), the smaller this range. There are any number of reasons for results to be inexact, but we can sweep all of them under the same carpet labeling them all “error”; keeping track only of their total size using (usually) standard deviation or variance. When you see the expression “3±0.1”, this represents a random variable with an average of 3 and a standard deviation of 0.1 (unless someone screwed up or is just making up numbers, which happens a lot).

When adding two random variables, (A±a) + (B±b), the means are easy, A+B, but the errors are a little more complex. (A±a) + (B±b) = (A+B) ± ?. The standard deviation is the square root of the variance, so a2 is the variance of the first random variable. It turns out that the variance of a sum is just the sum of the variances, which is handy. So, the variance of the sum is a2 + b2 and (A±a) + (B±b) = A+B ± √(a^2+b^2).

When adding numbers using significant digits, you’re declaring that a=0.5 x 10-D1 and b=0.5 x 10-D2, where D1 and D2 are the number of significant digits each number has. Notice that if these are different, then the bigger error takes over. For example, . When the digits are the same, the error is multiplied by √2 (same math as last equation). But again, sig figs aren’t a filbert brush, they’re a rolling brush. √2? That’s just another way of writing “1”.

The cornerstone of “sig fig” philosophy; not all over the place, but not super concerned with details.

Multiplying numbers is one notch trickier, and it demonstrates why sig figs can be considered more clever than being lazy normally warrants. When a number is written in scientific notation, the information about the size of the error is exactly where it is most useful. The example above of “1234 x 0.32” gives some idea of how the 10’s and errors move around. What that example blurred over was how the errors (the standard deviations) should have been handled.

First, the standard deviation of a product is a little messed up: . Even so! When using sig figs the larger error is by far the more important, and the product once again has the same number of sig figs. In the example, 1234 x 0.32 = (1.234 ± 0.0005) (3.2 ± 0.05) x 10-2. So, a = 0.0005 and b = 0.05. Therefore, the standard deviation of the product must be:

Notice that when you multiply numbers, their error increases substantially each time (by a factor of about 1.234 this time). According to Benford’s law, the average first digit of a number is 3.440*. As a result, if you’re pulling numbers “out of a hat”, then on average every two multiplies should knock off a significant digit, because 3.4402 = 1 x 101.

Personally, I like to prepare everything algebraically, keep track of sig figs and scientific notation from beginning to end, then drop the last 2 significant digits from the final result. Partly to be extra safe, but mostly to do it wrong.

*they’re a little annoying, right?

Hmmm. Cool. You know, when I was in school and had to grok things like sig figs, it never occurred to me that we were actually talking about train-wrecks with errors. I was just trying to pass exams by not making mistakes with significant figures. Now that I’m substantially older, it’s neat to see that I was totally missing the boat when I was in school. Who knew? So that kinda leaves the question hanging in the air of how do you learn what you need to learn while you’re in school? Or something to that effect.

“Rather than writing a number with it’s error”

That should be: “Rather than writing a number with its error”.

The apostrophe is used to denote possession except when talking about third-person singular neuter.

@Ling Guist

Thanks!

I really like this website! 🙂 thanks for updating it..

Thanks for this article! Here’s a sig fig paradox that maybe you can resolve:

There are two standard rules given in highschool for adding and multiplying sig figs. Take these two numbers: a=7 and b=11, where 7 has one sig fig and 11 is exact.

7 x 11 = 77 –> 80 (with one sig fig).

The product above must be rounded to one sig fig because of the multiplication rule.

Now, since 11 is exact, we can say this:

7 x 11 = 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7,

where each 7 still has its one sig fig. Using the addition rule:

7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 = 77 (with two sig figs).

So, depending on which sig fig rule you use, a x b = 80 (8 x 10^1) or a x b = 77 (7.7 x 10^1). How can this discrepancy be explained, and which (if either) answer is more correct, and why?

Eli exposes the flaw in sig figs! – January 2018

How can you determined the number of significant figures by the number of real digits when you know nothing about uncertainty. How 123 can have three significant digits if its uncertainty is 50%.

multiplication results in addition of relative uncertainties. Assuming the definition that a number such as 1.5 with 2 significant digits should have a relative uncertainty < 10 percent. Assume relative uncertainty is 7%. What if we multiply by 3.2 with 8% of uncertainty. By rules the result should have 2 sig figs. but looking at the relative uncertainty this is ridiculous as the relative uncertainty in the result will be 14% which is greater than 10% and hence you cannot claim two sig. figs.

Anyone to explain?

Well… I still don’t totally understand this explanation because I’ve never been properly trained in the uses of variances and other statistical methods, but this suddenly makes sig figs both more and less interesting to me. As a chemistry teacher, I have used and taught the use of sig figs for the better part of my lifetime with really only the fuzziest of understandings as to why and how the system works. I now see that the sig fig algorithms are essentially just a heuristic that bypasses doing some pretty gnarly statistical calculations for the sake of brevity and givis a communications standard by which scientists and students/educators can agree on whether a calculation has been set up and executed properly.

A very biased view of a mathematical tool (significant figures) which is very useful when used in appropriate situations. There are other such tools in mathematics, science, and engineering that work better in some measurements and computations. None are perfect but most are useful in their own domain.

I saw problems explaining sig digs a few years ago while teaching an intro chem course. I wasn’t going to teach the rigorous propagation-of-error algorithms I studied many decades ago (in high school, believe it or not, but too sophisticated for the level these adult community college students needed), but the rules for sig digs/figs they were given by textbooks and other materials were misleading. What sig digs are really mostly about is COMMUNICATION of the precision in some data. It’s about how to glean info on precision from a printed number and how to pass it on to the next reader without “plus or minus” data. Sometimes the only simple way to do that is with a vinculum over the sig digs. Otherwise the rules the students were taught by others wiped out sig digs in cases where low-order digits happened to add up to zeros.

The way I used to introduce the concept of sig digs to non-science majors was to use other ways we communicate quantitative precision in speech or writing. “Would I be lying if I told you two events that occurred 8 days apart occurred a week apart? What sort of different impression do you get from someone’s referring to a period of 2 days than from referring to a period of 46 hours? Why might someone say one versus the other?”

The subject should be taught along with examples of how to infer precision from a series of readings from instruments such as an electronic balance or a ruler. I noticed one lab handout my students in another course were given (copied from a textbook IIRC) gave a ridiculously rigid rule about interpolating readings from a ruler that seemed to take no account of what the human eye could actually see.