Physicist: Whenever you listen to a physicist drone on about relativity (and thank you for your time), you’ll often hear them say things like “…from the perspective of a moving observer…” or “…the observer sees…”. That’s all very fine and good, but how do you actually define the perspective of that observer?

When you describe something from your own perspective you say things like “it’s ten feet in front of me” or “it’s to my left” or “it passed me by at 30 mph”. You personally define a set of directions (forward, left, etc.) and distances (however far away something is) relative to yourself. Far more subtly, your perspective also includes time. The “future direction” is just as personal and subjective as all of the other direction and distance stuff. The subjectiveness of time was one of the great insights of Einstein’s relativity.

A short, more pedantic answer is that the observer determines the coordinate system. That’s just the mathematical way of saying that when you talk about the location and time that things happen, you just describe them in terms of your location and what your watch says.

We’re so accustomed to sharing a coordinate system, like (so called) universal time or latitude and longitude, that it’s easy to fall under the assumption that there really is such a thing as “correct coordinates”. In reality, such “universal coordinates” are useful only because they’re something a lot of people have bothered to agree on. And to be fair, it is a lot more useful to tell someone where you are in terms of street corners or latitude and longitude than it is to use your own personal coordinate system, which would amount to saying “I am where I am”. Philosophically interesting, but not useful.

So while you could describe an observer’s trajectory through a city using some kind of standard coordinate system, that’s not the observer’s perspective. That’s a description of their location using someone/thing else’s perspective. Form their own perspective, an observer doesn’t observe their position changing so much as they observe the city moving around them.

As you read this, you would be well within your rights to say “the screen is two feet in front of me” (or however far it is) or more succinctly “the location of the screen is x=2” (where the x direction is forward, the y direction is left, and the z direction is up). From anyone else’s perspective, the location of the screen is different. For the person sitting next to you on the subway (if you’re reading this on a subway), the location of the screen might be “x=2 and y=3” or even more succinctly “(2,3,0)”.

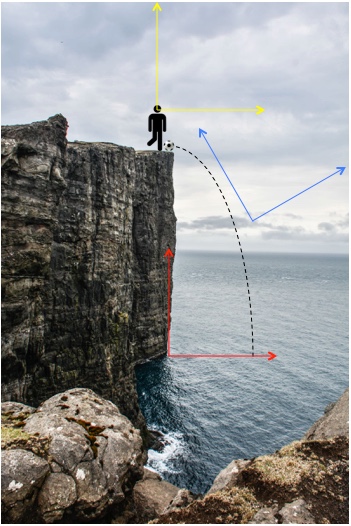

If you’ve ever taken an intro physics course, you’ve been subjected to the parable of the guy kicking a ball off a cliff. The problem is something like “there’s this guy at the top of a 20 m tall cliff who, in a sudden pique of ludophobia, kicks a ball off of the cliff so that it is initially traveling sideways at 3 m/s. Where does it land?”. The answer, you will be thrilled to learn, is about 6 m from the base of the cliff.

When you’re setting up this problem you’re faced with an ancient conundrum that has been haunting physicists since long before the age of cartography: what coordinates should I use? The most correct answer is: whatever lets you be as lazy as possible.

The yellow coordinates are the point of view of the kicker, the red coordinates are the most convenient, and the blue coordinates work fine, but they’re awful.

If you put the center of your coordinates at the base of the cliff, with the axes aligned with the ground and the cliff (red axes in picture above), then one axis gives you height off the ground while the other tells you distance from the cliff. Very convenient. In this case the base of the cliff is at (0,0), the ball is kicked at (0,20), and lands in the water at (6,0). You could use the kicker’s point of view (yellow axes), in which case you would describe the base of the cliff as 20 m below them, and the ball lands 20 m down and 6 m out, (6,-20).

The beauty of physics is that it’s capable of imitating the universe’s supreme deference. You can write physical laws without ever specifying coordinates, allowing us to define the stage (make up coordinates) and let the universe play out however it likes. So if you really, really wanted to, you could use completely arbitrary coordinates (blue axes). But don’t. The level of the water is no longer just “z=0” or “z=-20”, it’s an equation. Gravity no longer points in the “negative z direction”, but off to the side. You can still do the problem and by applying the exact same physical laws, but you have to do a lot more work and that’s categorically unacceptable for a physicist.

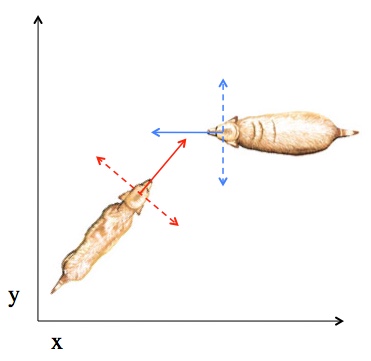

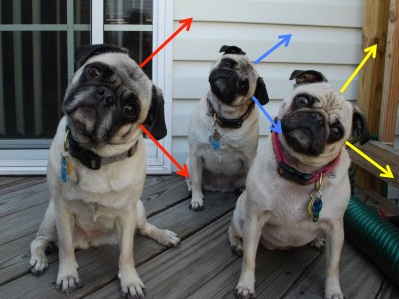

In normal space, direction is part of the coordinate system (forward, left/right). We’re already used to that notion when we talk to each other (as in “You’ve got something on the left side of your face. No my left, your right. Well it’s all over the place now.”). And you already know how to change your coordinate directions. If you want your “left direction” to become your “forward direction” you just rotate 90° to the left. If you want your “up” to become your “forward”, just rotate backward 90° (lie down). Easy.

Observers oriented differently relative to each other will disagree on what directions “forward” (solid lines) and “sideways” (dashed lines) are.

In relativity, the future is just another direction. Obviously time is a little special. You can measure distances in any spacial direction using a ruler or string, but to measure “distance” in the time direction you need a clock. So to define an observer in relativity, you define a coordinate system with them at the center and a time defined by what their clock says.

It’s hard to picture the “time direction”. Firstly because it requires thinking in four-dimensional terms and secondly because clocks and rulers are super different. That’s why physicists futz about with math and coordinates all the time; they allow us to extend our intuition from what we can picture to what we can’t.

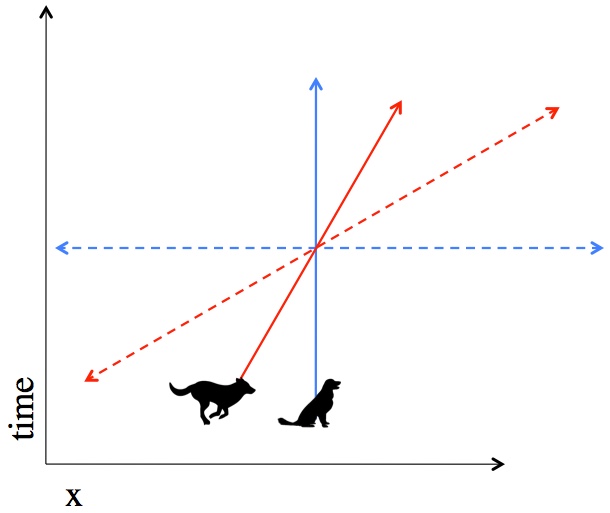

It turns out that you can do something similar to changing direction with time. Exchanging one direction in space for another is called “rotation” (no big deal). Exchanging one direction in space for the time direction is called a “Lorentz Boost” or, if you don’t speak physicist, it’s called “start moving in that direction”. Someone facing a different direction relative to you will have a different perspective on what the “forward direction” is and someone moving relative to you will have a different perspective on what the “future direction” is.

Observers moving differently relative to each other will disagree on what directions “future” (solid lines) and “now” (dashed lines) are.

So when you hear things like “when something moves very fast it experiences less time” it’s important to parse out whose time you’re talking about and even what moving means. This is actually a statement about how things behave in your perspective. As the observer, time and space are defined relative to your position and clock. When someone is moving, they’re moving relative to you and according to your coordinate system. When someone is moving through time slower, it’s according to your clock. The real headaches kick in when you realize that from the perspective of the other person, you’re the one who’s moving and experiencing time slower. This feels like a contradiction, but keep in mind that different observers all have their own clocks and coordinates. There’s a lot more detail on that here.

Here on Earth we’re all moving at about the same speed. The fastest someone else is likely to be moving relative to you is at most 2000 mph (if you happen to be both on opposite sides of the Earth and on the equator). Relativistic effects, including disagreeing about time, are only worth talking about when your relative velocities are an appreciable fraction of light’s modest 670,000,000 mph. The most accurate clocks in the world are capable of detecting disagreements induced by walking slowly (relative velocities of less than 1 meter per second). But we humans don’t care about differences of a few parts in a quintillion, so while the differences in our clocks are detectable (when we work really hard to detect them), they aren’t worth worrying about.

From that awesome description and explanation, wouldn’t we then also have to conclude that there is no subject (the subject that is measuring)?

@SheilaK

Thanks! How do you figure?

When you use the number 670 billion mph, is that only the speed from our earth bound observation? Or is it a fineite number? Lets say, we were on a significantly bigger planet with a significantly faster orbit around star that had itself a significantly faster speed through its galaxy. Would that number change?

@Jeff

That’s one of the two big rules of Einstein’s relativity: the speed of light is always the same no matter what. All of the weird effects on time and space that show up for fast moving things are ultimately due to that weird (but extensively verified) fact.

That’s where it gets hard to wrap my mind around. The two observers can agree on how many miles per hour the same thing is traveling, yet don’t agree (for lack of a better term) on what an hour is.

@Jeff

If two observers agree on the velocity of something (velocity = speed and direction), then they’re stationary with respect to each other and have the same notion of time. If they’re looking at each other, they may have the same speed, but will have opposite velocities. I.e., Alice will see Bob traveling north at 30 mph and the Bob will see Alice traveling south at 30 mph.

@Jeff

It is difficult to wrap your head around time not being observed to be the same by different observers at different velocities because in our daily lives, the velocities that we observe are so small, that time dilation is too negligible to often even be measured. However, the reality is that the only measurement two observers will agree upon is that of the speed of light. In fact, it is for this reason that time itself is not measured the same in two frames with different velocities.

Thanks, great explanation of a topic that isn’t often addressed in any detail!

This is a really good post and I would very much like to know what your take on famous double-slit experiment. Thanks!

The double-slit experiment is an experiment in which a single particle is emmitted at a specified rate. The particle is expected to go through one of the two slits, but in the experiment, we have screen to record to the arrival of the particle to the other side. However, against expectation, there is an interference pattern which occurs, which is uncharacteristic of a particle, and it is said the particle interferes with itself. The reason this occurs is because the trajectory of the particle is not a well-defined curve in Euclidean space, but rather, the position of the particle at any given time can only be characterized by a probability distribution, which is obtained from the wavefunction. This explains the interference pattern: the screen recording the arrival collapses the wavefunction, and the reason the interference pattern occurs is because it is predicted by the probability distribution.

There is a way to travel thousands of times faster than the speed of light and everybody sees it daily but it is not registering.

Ok Tom, you got my attention! Please enlighten me, because I believe what you’re saying to be true. Great minds have spent their entire lives looking for answers in all the wrong far off places, but yes, I too believe if they could slow down, stop and look closer to home, forget about what and where their told to find the answer(4getaboutit)all of it is meant to steer those wrong. I did notice you weren’t part of the original discussion, but rather commenting a couple years after. I felt that was the case, but of course as there was no one to chime in directly after your comment, like WTF! More less would the controllers even let you give that 2 cents while the forum is still live with the smarty pants gang and all their fancy cred-ain’t-yours, I mean credentials. No I don’t. Anyways, I should be going, but I would love to hear your insight, Tom, and maybe you can share with me a little more in-depth on what your beliefs are in reference to what people can’t grasp that’s right in front of ‘em. I won’t hold my breath that you’ll be back this way. Instead, I’ll just picture it as reality, like it already happened, so we’ll talk to you soon then, yes😉 -Cheers-