Physicist: It depends on what you mean by “free will” and where you draw the line on “determinism”. Both of these are a matter of opinion, so philosophers (and the rest of us) will have plenty to argue about for the foreseeable future.

If our choices are expressions of the activity of nerves cells, which are soggy bags of molecules clacking together (to paraphrase Gray’s Anatomy), which are governed entirely by fundamental universal laws, then everything we do is dictated by physical mechanics. Even the feeling that we have free will would just a bunch of atoms all following the same set of simple rules every time they meet another atom, repeated super ad nauseam.

So if physical laws are all deterministic, then everything anyone does is just as “fated” as a rock rolling down a hill or a clock chiming. Now, you may be lacking free will in some idealized sense, but if there’s no way to tell, then what are you really missing? Whether your actions are predictable in theory is not quite as important as whether your actions are predictable in practice. The tiny, individual interactions that make up everything we do are easy (well… kinda) to predict, but big systems are a lot more complicated than the sum of their parts.

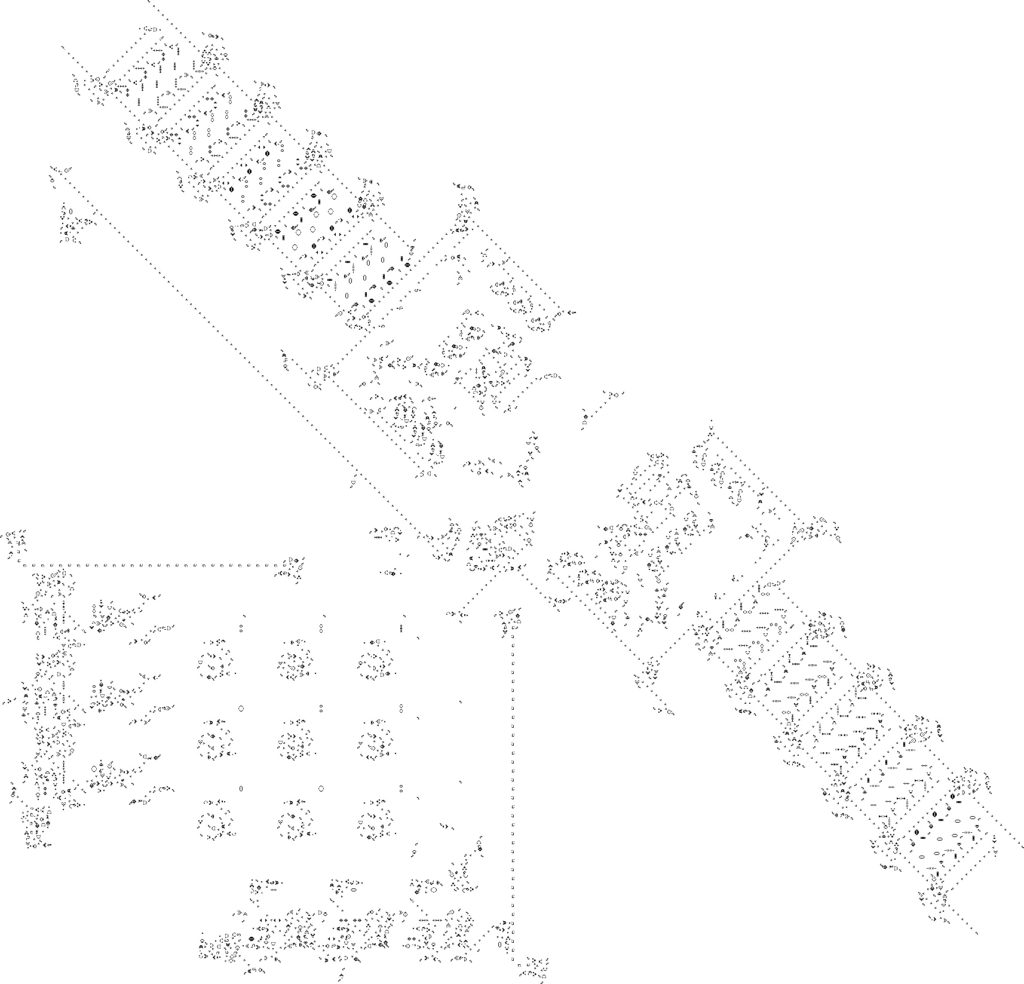

Conway’s “Game of Life” (different from the one where the goal is to die rich) provides a beautiful example of this. The Game of Life, which really should have been called “Staring at Pixels”, is a very short list of rules applied to pixels on a grid that describes which will be “alive” in the next “generation”. Systems of tiny, simple things (like pixels with basic interaction rules) are called “cellular automata”.

Each pixel borders eight others. If a “dead” pixel borders three “living” pixels, it comes to life in the next generation. If a living pixel borders two or three other living pixels, it stays alive. Otherwise a pixel dies.

If you’re not familiar with the Game of Life, it’s well worth taking a moment to play around with it. Despite baby-simple rules that only govern individual pixels and their immediate neighbors, the ultimate behavior of the Game can not, in general, be predicted from the initial conditions without actually running through the generations. In fact, the Game of Life is capable of the same level of complexity as the computer that runs it (if allowed to run on a large enough grid); so a computer can simulate the Game of Life, but at the same time the Game of Life can simulate a computer.

A computer, simulated in the Game of Life, simulated in a computer, replicated on a screen, and perceived by someone (perhaps) with free will.

The Game of Life is to free will, as a misplaced red wig full of bearer bonds is to clowns. If you spend enough time with the former, you can’t help but ask probing questions about the latter. Whether you’re talking about neurons or molecules or fundamental particles, people are also made up of lots of tiny “cellular automata”. The behavior of every little piece follows a set of known rules, so in theory you should be able to determine the outcome of even large systems (like people or worlds or whateveryougot) so long as you know everything about the initial conditions. But in practice: nope.

First, you’re not going to figure out the exact position of every particle in any system anywhere near as large as a person, and even if you could, the universe is right there to pile on more stuff to keep track of. Look around. See anything at all? Then it’s happening already.

Second, like the Game of Life, it’s unlikely that there’s a “computational short cut” for physical systems. That is to say, if you wanted to precisely predict what a person will do and think and whatever else, you’d have to simulate all of their bits and pieces, run the simulation forward, and see what happens. But that’s exactly how you handle a being with free will: you just… see what they do. Maybe this wild train we call life is on tracks, but if there’s no way to know where that train is going without actually riding it to the destination, what’s the difference? That’s at least free-will-adjacent.

That all said, the universe is not entirely deterministic. A little over a decade ago Conway and his buddy Kochen, defined something to be “free” when its actions are not explicitly determined by the past, and then proved the “Free Will Theorem” which is both profoundly bonkers and deeply frustrating:

If people have free will, then so do individual particles.

The difference between scientists and philosophers, is that scientists force each other to nail down exactly what they’re talking about and philosophers tend to be a little more loosey goosey (also, scientists are big fans of empirical evidence). So while you may disagree with how they defined the “free” in “free will”, that just means we need more words to work with.

In their paper, they spend buckets of time establishing a known physical principle, “fundamental randomness“, and just a little establishing what in the hell they’re talking about. To wit:

“Why do we call this result the Free Will theorem? It is usually tacitly assumed that experimenters have sufficient free will to choose the settings of their apparatus in a way that is not determined by past history. We make this assumption explicit precisely because our theorem deduces from it the more surprising fact that the particles’ responses are also not determined by past history.” -Koch ‘n Con

Here’s the idea:

For most of history, scientists labored under a rather modest assumption; that all possible experiments have a result, regardless of whether you bother to do those experiments. For example, if your experiment is “is this card the queen of spades?”, then there is an answer whether or not you actually look. By looking you gain a little information, but the result is there whether you bother to do the experiment or not. The card is whatever it is.

Even better, if you have a bunch of cards, it doesn’t matter which you choose to look at; all of them are what they are. If you assume that things are in definite states just waiting around to be uncovered, then there are a variety of mathematical statements you can make that are always true. Statements like “if there are three cards total, then there are a different number of red and black cards”. No matter how clever you are with actual playing cards, this statement (and a hell of a lot besides) must be true.

There are often multiple experiments/measurements you can do with a given system. If the result of each measurement exists before you look, then there are some mathematical statements that can be made about the collective results.

But it turns out that a lot of quantum phenomena, entanglement in particular, are incompatible with some of the equations that come from the assumption that “each card (or particle in this case) already is what it is”. In their paper, Koch ‘n Con provide an explicit example of an incompatibility based on particle spin and this old post goes into a lot more detail on another example, the math behind it, and what it means. The point is: seriously, as weird as it sounds, for many quantum systems it is literally impossible for the results of all possible experiments to exist (and therefore to be predetermined) because those results would be logically inconsistent with each other.

Now, if you assume that everything that happens is completely predetermined, then this isn’t actually a problem. The weirdness of quantum mechanics, the experimenters, and the experiments they choose to do, are all “on tracks”. The person doing the experiment had no choice about which experiment to do, which means that the result of only that one experiment needs to exist. The others won’t be done, so they can be safely swept under the existential carpet.

On the other hand, if the person doing the experiment has free will (in the sense that their actions are not determined by the past), then suddenly there’s an issue. If they’re free to choose any experiment and the result of that experiment is predetermined, then all of the results have to be predetermined. But that’s impossible.

Of course when we do these fancy quantum experiments we always get a result. No big deal. But if we have free will in the sense that our behavior is not entirely determined by the past, then the quantum systems we’re playing around with have free will in exactly the same sense.

The universe would need to be dead-set on conspiring against quantum theorists on a massive scale, and in a very specific way, in order to create the experimental results we’ve seen so far. In order to back up the assumption that the particles involved, the experimenters, and the machines used to do the measurements aren’t all subject to some all-encompassing, atom-by-atom, perfectly executed, and needlessly nefarious systematic bias, the methods used to make the “choices” in the experiments have become a little over-the-top. For example, by measuring entangled particles fast enough and far enough apart that light can’t travel between them, and by using cosmic microwave background radiation from opposite sides of the universe to randomly orient the measurement devices after the entangled particles are created and but before they’re measured. That way, either you really are randomly choosing which experiment you want to do, or the entire universe has been conspiring against you and this particular experiment since the beginning of time. It’s important to be sure about things, but this level of caution can blur the line between due diligence and paranoia.

It’s an open question whether the quantum randomness of particles scales up to produce free will, or at least “not-predetermined-ness”, in living critters. Forced to guess, I’d say… maybe/probably? Brains can turn on a dime and unless they’re actively suppressing it, eventually that quantum randomness should “butterfly effect” its way into our actions. At least sometimes. But if you really want to ensure that your will is as free as an atom’s, you can always carry around a Geiger counter and base all of your decisions on what it reads. You’d be the free-will-est person on your block!

Would be much better before starting such a long article, just to define in one sentence what free will is (or give several such definitions if there are). After all this is a scientific website isn’t it?

My phone has a free will. Sometimes it wills to recognise my fingerprint and lets me in and sometimes it doesn’t. In fact I can never predict. I try again and again, at last I give up and enter the PIN.

And also London’s weather has a free will. You can never be 100% certain if it will rain or not.

Is free will just an inability to know in advance with 100% probability what the answer of the complex system will be?

@Leo

That’s a definition, but it certainly doesn’t follow the spirit of what almost anyone would call free will. We’re a little hampered in scientific circles without a useful, standard definition for consciousness, or choice, or free will, so we’re forced to use stand-ins like “not predictable”.

Well… How is free will of a guard at the club entrance who imposes face control is essentially different from the AI face control using videocamera? I think the problem of “free will” or “consciousness” or “soul” is that these terms appeared in a pre-scientific era. Before computers, algorithms, brain research – these notions could not be studied and could not be determined. In modern science these terms do not exist, because they are useless and do not have any valuable meaning (i.e. within science).

@Leo

Totally.

Typical Materialist answer and it’s full of nonsensical minds wearing braces, trying to impress us. No one knows what consciousness is, especially the physicists, who are not qualified to even begin to answer this question. One of the best physicists of the 20th Century, Richard Feynman, could not adequately explain the results of the Double Spit experiment. You have no idea what “will” is, let alone stumble along with your gears, wheels and bags of chemicals for an explanation. The computer simile fails on many dimensions of thought, not the least of which, is again, the question of Consciousness. If you think that it, consciousness arises from 3lbs of meat, or can arise from the arrangement of plastics and other materials with some electrons flowing through….you are deluding yourself. Consciousness is the primal matrix of being itself. Matter, is just one of it’s expressions. Free Will is a concept based on as yet inadequate understanding of Being.

Not true; everyone knows what consciousness -is-, it’s what they’re experiencing right now and have experienced every day of their lives. Everyone has first-hand experience of consciousness and can instinctively tell the difference between being conscious and not being conscious.

What we lack is the ability to explain how consciousness works with language to other people in a clear and concise form. ‘I think, therefore I am.’ Tells you what consciousness is (assuming you are conscious), just not how to explain it.

Unfortunately, a language originally developed from the methods of communication used by tree-dwelling primates to show each other where the tastiest fruit can be found is ill-equipped to explain complex philosophical questions about the fundamental nature of being. Even with math.

“Fate” is a relative term, to one that desires and sees only a certainty, even chaos is fate and therefore, chaos = a planned and determined outcome, the end result will always be what the propagator of “Fate” wishes and as such “Free Will” can NOT exist.

Whereas those who know of the paradoxical certainty of free will see not chaos not but infinite possibilities including action and inaction, free will knows not the long term but the short, even if one feels they can predict a set of choices, the chaos of the universe forces constant reconciliation of the present to decide yet a different future even if that future is true to his intentions….at that time.

Can “Free Will” exist in a universe of chaos? Ask yourself this…..

Is it “Fate” or “Free Will” that forces us to recognize our need for a thing yet act in contradiction to that recognized need.

“We’re all mad here, you’re mad, I’m mad, you must be, or you would not have come here!”

This website is called “ask-a-mathematician” not “ask-an-ancient-philosopher” “ask-a-metaphysical-person” or “ask-a-theologian”, right?

In mathematics it is common to first define a subject, then discuss it.

Nobody here defines free will, but all jump straight to discussion.

And so it is a strange debate: the subject is not defined.

(“Fate” is yet another such undefined term).

I proposed a definition of free will couple of posts above, if you want to discuss that definition, you are welcome, if not please give yours, I will be happy to discuss it.

(J. Allen Hewitt – we are not mad but lonely and don’t have whom to talk to on subjects we are interested in. XXI-st century…).

How does the impossibility for the results of all possible experiments to exist relate to the Many Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics?

@squi

At the same time that we cannot describe quantum systems in terms of unknown-but-definite-states, we can easily (and very successfully) describe them as “superpositions” of states. Something is in a superposition of states when it is literally in multiple states at the same time.

I get nervous using the term “many worlds” because it implies that there are other worlds. Things can be in multiple states, and those individual, mutually exclusive states don’t ever seem to notice each other, but they’re all in the same “world”. When you do a desktop double slit experiment, the distinct versions of the photon that go through each slit are still on your desk.

A good rule of thumb in quantum physics is that “everything that can happen does”, in the sense that every possible state contributes (verifiably) to the superposition of states. When we do these same experiments in careful isolation we find that all possible results are included simultaneously. You can certainly call those simultaneous different results “different worlds”, but it’s a little safer to say that our one world is merely weird.

Question for the ‘ask a’ guy:

What makes you think free will is removed if the process of making choices can be predicted or described?

There are a lot of processes that can be predicted and described, but we don’t normally assume that this alters them in some way.

To assume that free will is removed by predictability, we’d need to understand time, and issues relating to…. predictability. And yet we don’t. Block time says everything is predictable, all of time is already laid out, and there’s no motion through time at all.

And yet to do physics, we constantly assume motion through time exists, which is also what we observe, or seem to observe. We use motion through time constantly, without understanding it, and thinking that it ultimately doesn’t exist.

So we can’t assume that predictability removes free will, as it’s all bound up with things we don’t understand. So the ‘free’ in free will doesn’t necessarily relate to those kind of questions.

@David

Fair enough!

I may not have underscored this hard enough in the post, but there isn’t a good definition of “free will” that is generally agreed on. “Predictability” is a halfway decent definition that (more importantly) physicists can actually talk about, but it’s not the definition.

Predictability has nothing at all to do with free will. If that’s the accepted definition of free will from a “scientific” perspective then it’s dead wrong. Whether one can predict something does not disprove free will. Even if a prediction was made correctly, it would not mean that the prediction was correct, but only that you happen to predict the correct outcome, which was one of many outcomes. If I predict the score of a hockey game I did not suddenly become the force that made it happen. Free will is outside the bounds of science completely. The great fallacy is that science can explain everything needs to be dropped. While science can use observation and experimentation to test physical laws, it cannot explain where such laws came from in the first place.

There are people who whatever science achieves and whatever discovers, will always imagine existence of something that is not possible to discover. Why do they claim this? Do they have any proof? No, this is how their brain works, this is in psychology. They love to think that some undescoverable force drives the world. Vitalists insisted there is a special, hidden, undiscoverable force that turns dead matter into the living one. Somehow voices of vitalists are not heard nowadays. But they never stop. At each stage of science they claim there is something unknown, impossible to discover that drives the world. What is the point of this?

We can’t assume either. It may be that science can know everything, or it may be that it can’t.

With physics we don’t know yet. But with mathematics, it turned out to have limits that no-one expected, when Godel found his incompleteness theorems. Penrose showed some limitations to the idea that AI can do everything that humans do. So in other areas limitations tend to show up.

But that doesn’t say much about physics. I’d say that as long as something counts as physics, physics can understand it. It’s just that we’re still trying to find out what counts as what.

@David, you are right, but there is a difference between claiming that science (i.e. physics, chemistry or biology) can know everything (I don’t think anybody ever claimed this) and inventing imaginary “driving forces” or “phenomena” which are unknown to science and cannot be disproved at the current stage. “Free will” is one of them, “vital forces” (which make dead matter to live) is another example, “gods” and “aliens” are from the same category.

For its research science chooses many different phenomena to investigate. The thing called “free will” cannot be one of them, because it is not a phenomenon. You cannot observe a thing called “free will”, it is just an exercise of people’s imagination. There are many such things invented by philosophers or other folk and those things are not phenomena, but a game of imagination. Science should not deal with things which are game of imagination, because it is out of its field. For this reason science should not deal with gods or other supernatural creatures.

If decisions are partially driven by a random number generator, then you still can’t control it. It controls you.

But even if everything is deterministic and you can perfectly predict someone’s decisions, you can’t tell them the prediction, because they can be predictably rebellious and do the opposite of what they’re told they’ll do. By the same token, you can’t predict your own decisions. See Newcomb’s paradox with transparent boxes.

Our impression of freewill is a phenomenon. We seem to observe freewill, just as we seem to observe motion through time. Both may be illusions, but science investigates what we seem to observe.

And both freewill and motion through time are assumed to exist when we do physics. We start with the assumption that we’re free to choose which experiments to do, and even though some have tried to explain the contradictions and weirdness of QM by saying that we’re not free to choose which experiment we do, that’s a weird peripheral view. Most people assume freewill to do physics. If you don’t, you get some stuff that’s even worse.

Sometimes we just have to accept that we don’t understand something. We work with it, it seems to exist, and it may well exist. We’ll probably understand it one day. Leo’s post seems to do this thing that many people do, which is to sweep under the carpet things we don’t understand. But progress is made quicker if we admit they exist, or seem to exist, and keep on thinking about them.

Our impression of paradise and hell and gods and angels and witches and devils is also a phenomenon. Let’s study all that and use quantum physics for this.

(Some time ago people would say about witches and devils: ‘We work with it, it seems to exist’).

Can you please describe an experiment which allows observation of free will?

@David, please describe an experiment showing existence of free will.

With both freewill and motion through time, we use the assumption that they exist to do physics. That’s why they’re different from various mythical creatures.

With motion through time, it’s not so much a case of testing to see if it exists. It’s hard to find an experiment that doesn’t seem to show it exists, and yet we tend to believe it to be ultimately unreal. We still have to work with it, without understanding it, that’s the point I’m making.

At the moment, there’s an amazingly contrived approach to QM that removes freewill, and says that if there’s an enormous conspiracy within the universe, so we only do certain experiments that give certain results, then it’s possible to try to explain some aspects of QM. To me this is basically giving up on trying to explain it, and instead resorting to ideas that are a bit like witches and angels. So it’s doing without freewill that’s the crazy unprovable idea here, and if you’re so against crazy unprovable ideas, then be sceptical about the removal of freewill.

PS. The reason I object to that approach to QM is that it removes the scientific method. In the scientific method, we have freewill to choose any experiment. Those people I mentioned try to explain QM by removing the scientific method. I think we should keep on trying to explain it without sacrificing the scientific method (it’s too high a price), which absolutely requires freewill.

Is this discussion not dealing with what is called “Quantum Mysticism”?

@Leo

I hope not.

In some more mystical (and less scientific) circles a direct connection has been made between quantum mechanics and consciousness. In this particular post the connection is this: a Canadian and a British dude decided that predictability is a good way to talk about Free Will and, by the way, quantum theory has some things to say about whether certain processes can be predicted.

@leo

That’s an easy experiment. Just ask me if I’d like a Reese’s cup.

@Jeff, thanks, but such a description is not enough.

What outcome should your experiment produce so it will prove existence of free will?

And also what outcome (or what other experiment) would disprove existence of free will?

(Popper’s falsifiability)

I don’t believe there’s a connection between QM and consciousness, but the jury is still out. I also think the jury is out on freewill. It’s worth remembering that the jury is sometimes out.

The idea that there’s a connection between freewill and predictability is hard to call for now, because we have problems reconciling block time with what we observe. And that affects issues about predictability.

Why wouldn’t there be a connection between QM and consciousness; there’s a connection between QM and everything else. What makes consciousness so special that you expect it to be the sole exception?

I mean a direct connection, of the kind that many think exists. There are indirect connections between everything and everything else.

Btw, one part of the question is ‘…in our deterministic universe’. Given what QM tells us, we can’t say that.

PS. I found this:

Q: Are the brain and consciousness quantum mechanical in nature?

Posted on September 3, 2012 by The Physicist

Physicist: The extremely short, smart-ass answer to this is: of course!

Sure there’s connection between QM and consiousness as well as between QM and computer programs and QM and Artificial intelligence and between QM and DNA and QM and politics and QM and economy and QM and computer games.

Quantum mechanics and quantum indeterminacy has nothing whatsoever to do with free will. If the universe is not perfectly deterministic (Bell’s Theorem proves it is not, though there is a theory called superdeterminism that attempts to get around that), then it does not mean we may have free will. It just means we have a sprinkle of stochastic random fuzz being added to our otherwise completely deterministic brains.

Also, I’m very disappointed that no one here has mentioned the concept of agency yet, which many people tend to confuse with free will. We absolutely have agency, but free will, which by definition requires us to be able to make decisions absolutely unimpeded by the laws of physics, is just impossible.

@mrjeff, notions like agency or free will are applicable only when you treat human brain as a black box. Indeed when these notions were invented, brain was an absolutely black box for any philosopher or scientist of the time. Nowadays this has changed a little bit. Brain is no more a black box. It is in essence a complex computer working on neuron networks. There is no point to argue relentlessly if free will or agency exist or don’t. It is much better to argue if specific algorithms or specific functionality exist or not in the brain. For example, the question in 21st century to ask is: “Are neuron networks deterministic or stochastic based on our knowledge of quantum mechanics?”

Or (thought experiment): “If we simulate human brain using computer, will it be possible to distinguish it from a real human brain?”

@Anonymous (above):

The idea the brain works as a computer does is only the most recent case of taking a recent invention and trying to reduce everything else to it. Nowadays it’s computers and Information Theory, so we naturally try to think of very complex stuff “as if it too were” computers. Just a few centuries ago the fashion was to think of brains in terms of clocks. Before than, in terms of billiard balls. And before that, in terms of fluid vortices.

Are brains computer like? Maybe. But that hasn’t been proven. It’s an assumption, and one could easily reverse it by saying that they’re evidently more than computers given how they invented computers, so computers are cannot but be a subset, maybe a small subset, of whatever brains actually are.

@Physicist:

One very huge problem with any attempt to treat free will using math and logic is that these two languages are themselves deterministic and include determinism as an occult premise in every step of every reasoning done with them. This results in that every single logical-mathematical argument about free will necessarily concludes, by effect of a subtle begging the question fallacy, that free will doesn’t exist. It’s built into it, and cannot be bypassed.

The alternative, if we want to talk logically about free will, is to assume free will as a given axiom. That it simply exists, period. And then use that axiom as a premise in the chain of reasons we’re constructing. From that, evidently, we cannot conclude free will exists, as that’d incur in the same fallacy. But then we’d at least have an alternative set of (deterministic) arguments that keep free will tagging along them.

It is possible free will doesn’t in fact exist, mind. As it’s possible it does exist and it’s a fundamental aspect of reality forever beyond the reach of any deterministically-bound language. But neither of those two assertions can be arrived at through that language. Whatever is said using it is biased in one direction or the other from the get go.

Your free will allowed you to choose whether or not to respond to this article and also gave you the ability to choose what to say. See how easy it is to prove free will? Seriously, people, get a grip on reality and move on.

@Tommy:

Whenever someone says “it’s easy!”, that person is wrong, no matter the subject.

@Anonymous: brains have not invented computers. Computers evolved.

That’s your scientific refutation to my position? Seriously, if you can’t see that you have free will to do things then your grip on reality is completely gone. Or are you going to argue that some cosmic quantum mechanical process forced you to answer a certain way? I guess my response, which is completely contrary to what your response is somehow proves we don’t have free will and yet somehow we oppose each other in contradictory views. I can just as easily come back and say I agree with you 100%. Or how about this. Here are 3 possible responses to your last response:

1. Occam’s razor would favor my point of view.

2. Your answer is merely speculation and opinion.

3. You failed to provide a scientific basis for your response.

Now, you choose which response that I give. That also proves free will. In fact, you can choose to ignore my responses and pick an alternate response. Or you can choose not to respond at all. Free will is proven in any of those cases.

@Tommy:

Your argument proves we all share the subjective perception of having free will. Yes, we do. It doesn’t prove the objective existence of free will, as one cannot naively assume subjective perceptions correspond to objective realities. They may correspond perfectly, or they may not correspond at all, or they may correspond only partially. Showing how much they correspond with each other, and why, is precisely the problem being discussed.

Here’s an analogous case: we all share the subjective perception of the Earth being fixed in place and mostly flat, and the Sun, the Moon, the planets and all stars moving around it. That subjective perception being shared by all of humanity doesn’t prove its objective validity.

Both facts, that we all share the perception of free will and the perception of the fixedness of Earth, are trivial and mostly uninteresting. What matters is whether those perceptions describe how the world actually is *beyond* our perceptions of it.

And the one shared trait among all scientific discoveries since at least the 18th century is that they *always* show human perceptions and intuitions to be wrong. So I don’t see a good reason for us to assume that in this specific case it’d be different.

It may be. Free will may be real. I *want* it to be real. But whether it is or not has to be proven. And *this* proof you neither have provided, nor can provide, because, as I’ve shown in my first answer, we lack the very language with which to properly discuss it.

Your analogy is an apples to oranges comparison. One is a perception of physical traits as viewed through human eyes and the other, free will, is not physical and is immaterial. So your argument falls flat.

My answers have absolutely proved free will. In order for you to disprove free will, you must provide a mechanism that, when given multiple choices, forces you to make one choice over another. In fact, before you can even go down that road, you have to prove that thought is merely the product of electro-chemical processes and that there is not an immaterial aspect to it at all. But if that were true then computers could become self-aware or even a rock for that matter. It reduces the whole thing down to complete absurdity. But that’s generally what happens when you reject the truth that we are creatures made in the image of God with a soul and spirit.

“And the one shared trait among all scientific discoveries since at least the 18th century is that they *always* show human perceptions and intuitions to be wrong. ”

Please list every single scientific discovery since the 18th century and how it proved human perceptions and intuitions to be wrong. You made a bold assertion that they were “always” wrong. Prove it aside from a baseless assertion.

@Tommy:

Ahhh! So you’re coming from a religious background! And using black-boxes (“immaterial”, “God”, “image of God”, “soul”, “spirit”) to pseudo-explain other black-boxes (“free will”, “self-awareness”). Good luck with that.

And I say that being a Shinto-Buddhist practitioner myself who talks regularly with Kamis such as Inari Okami and Amaterasu Omikami, Bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteshvara, and even, on the sideline, deities such as Anubis. “Talks” as in speaks and actually hears the answers, establishing very productive dialogues. So, yes, souls, spirits, rational non-human species, deities, reincarnation, magic, cosmic cycles and lots of other interesting stuff do indeed exist. But I have a hunch you wouldn’t want to hear about that side of the equation.

In regards to the mechanism, this link provides one, based on strict materialism. It’s a good intellectual exercise to understand it as a basis for further discussions:

https://wiki.lesswrong.com/wiki/Free_will_(solution)

As for “every” scientific discovery, nothing like asking an impossibly huge list of things so as to win the argument, eh? But I’ll provide a few broad strokes and a practical test:

a) The stars aren’t fixed.

b) Species aren’t fixed.

c) There’s no daily spontaneous arising of life from dead or inanimate matter.

d) The Earth is extraordinarily old, and everything about it changes.

e) Nature doesn’t operate in binary categories, but on curves.

f) Homosexuality and transsexuality are naturally arising phenomena.

g) Our small-tribe intuition on how to organize society cannot be applied on large scale without producing suboptimal outcomes.

h) Even more so for our economic intuition, which are directly opposed to how the economy actually works.

i) Intuitive math notions are a small subset of all math, and physical reality conforms to the expanded set, not to the intuitive one.

Now, it’s very easy to check any of this. Forget whatever you learned in school and college about any subject and think about what the version of you ignorant of all of that would think about those topics. Compare with what you learned. There you have, for almost all if not all of what you learned.

“As for “every” scientific discovery, nothing like asking an impossibly huge list of things so as to win the argument, eh?”

Ironic that you realize it’s an impossibly huge list and yet did not realize the implications regarding your assertion. If it’s an impossibly huge list then you couldn’t possibly have known all of them nor whether or not they were proven false. And that’s my point. You made a broad assertion just to make it sound like you had more knowledge than you actually had. So, who’s the one trying to just win an argument, eh?

“b) Species aren’t fixed.”

This was a secular concept. I think you’ll find that Biblical creationists never believed this. Just research Carolus Linnaeus and Athanasius Kircher. They were pre-Darwinian by the way.

“c) There’s no daily spontaneous arising of life from dead or inanimate matter.”

Interesting to note that it was a Biblical creationist, Louis Pasteur, who proved this wrong.

“d) The Earth is extraordinarily old, and everything about it changes.”

A concept arising from naturalism and evolution, but not supported by the Bible nor believed by Biblical Creationists.

“e) Nature doesn’t operate in binary categories, but on curves.”

I have no idea what this is supposed to mean.

“f) Homosexuality and transsexuality are naturally arising phenomena.”

No Bible believing Christian ever believed this.

“g) Our small-tribe intuition on how to organize society cannot be applied on large scale without producing suboptimal outcomes.”

A bit vague. And not really a scientific issue anyway.

“h) Even more so for our economic intuition, which are directly opposed to how the economy actually works.”

Not science either. Economics.

“i) Intuitive math notions are a small subset of all math, and physical reality conforms to the expanded set, not to the intuitive one.”

You’d have to explain this more. The one-liner doesn’t really say anything.

@Tommy:

0) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperbole

b, c, d, f) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ingroups_and_outgroups

e) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Normal_distribution

g, h) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_science

i) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-Euclidean_geometry

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paraconsistent_logic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayesian_inference

@Alexander

You can’t prove the objective existence of anything, because nothing is objective. At all. Full stop.

If you’re looking for objective proof of free will (or indeed, objective proof of -anything-), give up now because you are wasting your time.

What you should be looking for instead is the degree of subjectivity involved; the more people agree on a given point, the less subjective that point is. You’ll never reach true objectivity, but for things like basic physical laws you can get close enough to an object truth for most practical purposes.

Related: I perceive myself as having free will. Even if this is an illusion of some kind, as long as there is no way to break that illusion (and the uncertainty principle strongly suggests that there is not), then what is the practical difference to me? Is there one? And if there isn’t, does it matter?

To use a hypothetical, let’s say that the ‘multiverse’ hypothesis is true: That everything that can happen -does- happen in ‘parallel’ timelines. In such a situation, free will is technically an illusion. While any given single instance of ‘me’ might appear to have free will, in truth the conglomerate entity that is ‘me’ is entirely deterministic.

But I do not possess the viewpoint of that hypothetical conglomerate being, I am but one of those instances, and thus for all practical purposes, from my point of view, I am in possession of free will.

In such a hypothetical situation, do I have free will? Or do I not? And does it even matter if the end result is exactly the same regardless?

I agree with @Alexander that our perception can’t be trusted, and so therefore our perception of freewill can’t be trusted. But it’s easily enough to say that it can’t NECESSARILY be trusted. There’s no need to say that all discoveries show that it’s always wrong! (or to ask anyone to list all discoveries since the frigging 18th century). It’s sometimes right. But just a few discoveries that go against our intuition is enough to show that things are not necessarily what they seem. Science has taught us that – just the behaviour of clocks in different places, for example, is enough to show that.

Although I agree with @Alexander on a lot here, I think @Tommy made a very good point:

“In order for you to disprove free will, you must provide a mechanism that, when given multiple choices, forces you to make one choice over another.”

It’s very arguable that free will is innocent until proved guilty, ie, that we should take it to exist, with an open mind, unless it is proved not to exist. And we do – we use it in physics a lot, as I’ve said above. So the burden of proof is on that side of the fence, it’s the need to disprove it.

It’s hard to prove that it doesn’t exist, and, because when we look at closely related questions, such as “does the future already exist?” we find that our physics doesn’t give us reliable answers, and contradicts itself a lot on that.

The other good point in what @Tommy said is this: “In order for you to disprove free will, you must provide a mechanism that, when given multiple choices, forces you to make one choice over another”. This implies that it’s not predictability that negates free will, it’s being forced to make certain choices. That’s very different. I’ve argued above that predictability doesn’t necessarily negate free will. Here we’re looking at something that does indeed negate free will, and it helps if we can distinguish between them.

PS. About the free will theorem as described in the article: all they showed is that their definition of free will (not entirely determined by the past) is probably false.

But even if it were true, and human free will is about not having our decisions entirely determined by the past, that doesn’t necessarily mean that ALL things that are not entirely determined by the past involve free will. It might not work both ways. But in applying that definition to particles, and saying that particles have free will if we do, they assume it works both ways.

@David, science is not about disproving things that have been invented by human imagination. There are no scientific works which disprove gods, witches, aliens etc. Science is about phenomena that can be observed objectively, i.e. observed by different people, recorded and described in terms which don’t depend on specific person’s perception or imagination.

If you say, like many in this thread: “We all have free will because we are free to do things” this does not mean that free will is a phenomenon which can be observed or studied.

You need to describe how you observe this phenomenon and what experiment you use to prove it and what other experiment you would use to disprove it.

I will give here an example of such experiment. A person goes along the street towards T-crossing. At the crossing he or she can turn either left or right. Our experiment is to observe people coming to the crossing and recording if they turned left or right. Now, some people would say: the phenomenon of free will is when we cannot predict with probability of 100% if the next person turns left or right.

But if you replace person by dog, mouse, cockroach or a robotic vacuum, you also cannot predict with 100% probability whether it will turn left or right.

Which makes the above definition useless: anything has free will.

And also you can create a situation when you will be able to predict people’s way with 100% probability. Just position a tiger at the left side of your T-crossing and 100% of people will rush to the right side which is fully predictable. You can do similar thing for dog, cockroach or robotic vacuum. And so now nothing has free will.

So free will turns out something that we cannot define, observe and study. So free will is not a phenomenon and it cannot be studied by science and it is a product of people’s imagination like gods, ghosts, flying saucer etc.

The short answer is, “no”. But the reason being is that your question presupposes the truth of a deterministic-universe.

Think of it as a matter of levels of awareness amongst humans. Those that are aware of the possibility of free will are able to explore the ramifications, and thereby escape a cage of determinism. Those that accept determinism as truth, can and will never challenge that concept. They are like a person on a raft, that has floated into deep water. They will continue to be carried by the currents, because they don’t believe in the possibility of paddling, or attempted steering of the raft.

Those that choose to paddle, or kick, will alter the course of the raft.

The universe is both determinative and subject to free-will, but both concepts are created by the human mind, and are therefore subjective. There are no objective deterministic or free-will universes.

Wonderful write-up! I completely agree with your points.

Thanks for sharing