The original question was:

“Furthermore, you say, science will teach men (although in my opinion a superfluity) that they have not, in fact, and never have had, either will or fancy, and are no more than a sort of piano keyboard or barrel-organ cylinder; and that the laws of nature still exist on the earth, so that whatever man does he does not of his own volition but, as really goes without saying, by the laws of nature. Consequently, these laws of nature have only to be discovered, and man will no longer be responsible for his actions, and it will become extremely easy for him to live his life. All human actions, of course, will then have to be worked out by those laws, mathematically, like a table of logarithms, and entered in the almanac; or better still, there will appear orthodox publications, something like our encyclopedic dictionaries, in which everything will be so accurately calculated and plotted that there will no longer be any individual deeds or adventures left in the world.”

-Notes From Underground

I was wondering how these laws that Dostoevsky mentions could be catalogued. Assuming these laws that determine human behavior are indeed discovered, what could be done so that it would be easy to refer back to. If a possibility tree of some sort is devised it would be incredibly huge considering how slight adjusting of an action can completely change the result in the long run.

Physicist: Dostoevsky was writing from a very 19th century point of view; the “clockwork model” of the universe had proved to be an shockingly effective way to think about how physical principles play out. Chemical and thermodynamic processes, complex machinery, and the motion of the planets themselves all followed extremely precise, predictable “scripts” that were being discovered in rapid succession. For a while there it was beginning to look like all of the laws underpinning reality would soon be revealed and that the seeming chaos of the universe would be brought to heel shortly after.

And Dostoevsky may have had a point about predicting human actions. With little more than our every movement, correspondence, interaction, and continuously updated high resolution pictures of us and everyone we’ve ever known, big data firms claim to be able to alter our opinions and compel us to buy things.

But there may yet be a little wiggle room for free will. It wasn’t until the 20th century, with the advent of computers and some fancy math, that we had the opportunity to grapple with complexity, chaos, and the nature of randomness.

Chaos theory says that many everyday systems are unpredictable, because errors compound exponentially. Tiny errors become small errors which become big errors which become a useless prediction. Even if you have infinite computers, if you don’t know the initial conditions perfectly, then there’s only so much you can do. Weather is the classic example of this. Even though we understand the underlying laws and dynamics very well, tiny perturbations become larger and larger and quickly swamp any attempt to accurately predict the future behavior of the system. In ten thousand years people will still be complaining about the local weather person (or clone or robot or hologram or whatever).

Chaos theory is relevant to us and our minds, because chaos is a trick that neurons picked up hundreds of millions of years ago. Sometimes it’s important to produce a very regular predictable pattern, like the aptly named “pace maker cells” that control the heartbeat of every creature with a beating heart. And consistency itself is important, for example if you’re a part of a society and those around you rely on that consistency. But often it’s useful to have a ready source of unpredictability. For example, if you need to run from an animal, it’s important to zig just as often and unpredictably as you zag. Hunters and foragers also need randomness for certain “I have no idea where to start looking” searches. Fortunately for us brain’d creatures, nerve cells are capable of chaotic behavior.

The chaotic nature of nerve cells implies (among other things) that when you inevitably meet a painting chimp, there’s no way to predict the quality of their art with certainty.

Noisy systems aren’t automatically chaotic. Chaos is rooted in inherent instabilities and a sensitivity to tiny changes. You can certainly have turbulence in water, but that doesn’t mean that fluid flow is necessarily chaotic (although it is sometimes). On the other hand, systems like a three armed pendulum or an LRC circuit with the capacitor swapped out for a diode (to add some non-linearity) are chaotic. We can detect the “signature of chaos” in these systems and in the responses of cells and groups of cells.

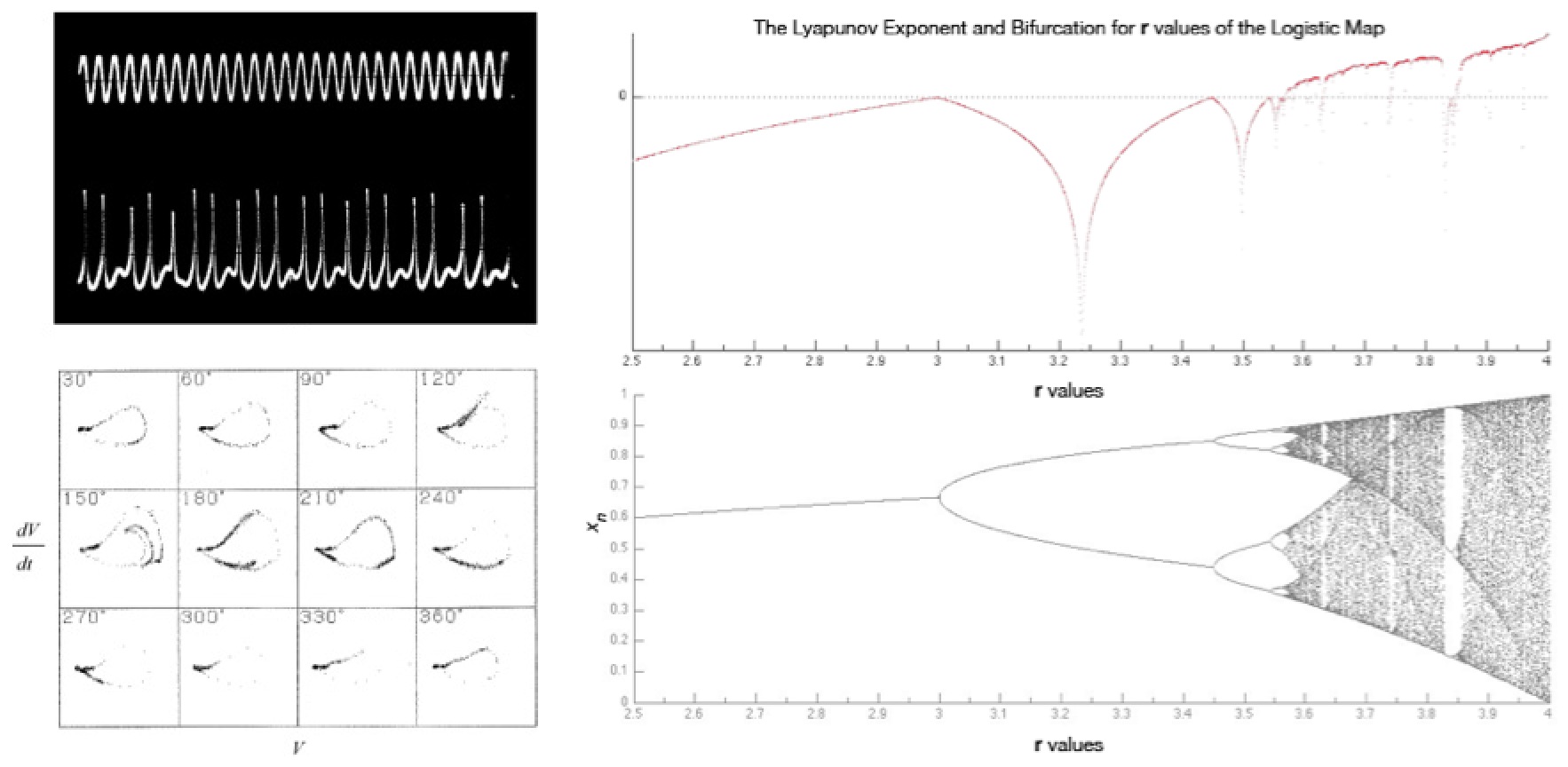

In particular we find that these systems will respond to periodic (repeating) inputs with an aperiodic output; they continuously throw themselves out of step and never quite return to the same state. Even more symptomatic, as with other chaotic systems, nerve cells demonstrate bifurcation before they become chaotic. As some parameter in the driving signal is increased, the neurons will follow patterns that take two cycles to complete, then four, then eight, and so on, with each bifurcation occuring sooner than the one before until they never repeat at all and become officially chaotic.

Upper Left: A sinusoidal driving voltage and the response of a single squid neuron. Lower Left: Each box is the voltage vs. rate of change in the voltage at the same point in the cycle recorded over and over and over. Non-choatic patterns produce only one or a few dots because the pattern repeats (nearly) perfectly. Lower Right: The stable points in the logistic graph (a very simple mathematical chaos model) vs. a changeable parameter, “r”. Upper Right: When the “Lyapunov exponent” (a measure of instability) is negative the system is self-stablizing and repeating. When the Lyapunov exponent is positive the system is chaotic and never repeats. For chaotic systems, the approach and “transition to chaos” is usually pretty clear.

So there’s a good chance that brains are like weather, with climates of mentality, El Ninos of mood, and flash floods of thought. And of course, predictable monsoons of commerce. But while it may be possible to predict that it’s likely to rain tomorrow and you’re likely to buy an umbrella, it’s probably impossible to predict your dreams. Remembering the way someone ate a sandwich weird, fifteen years ago, may be one of those outcrops of chaos your brain is capable of creating. A song that always made you cry suddenly becoming funny may be as impossible to predict five seconds out as a tornado five months out.

On the other hand, we may be clockwork. It’s hard to directly correlate the chaotic nature of isolated groups of neurons with the ever-changing large-scale behavior of people.

So here’s the point: like weather, your moment-to-moment thoughts and actions are yours alone. Perfect prediction of a person is likely to be impossible, because neurons are capable of truly chaotic behavior. That means that even with an atom-perfect brain scan, if the brain is chaotic, then its behavior can’t be predicted for long.

But like climate, a gross estimate of your behavior can be pretty accurate. There are general rules, varying from person to person (which we may as well call “personality”), that can be used to roughly predict how someone will behave. So far, the techniques that seem to work best are “getting to know someone real well” and “machine learning”. Get a big computer to stare at lots of people as much as possible, and those behaviors it is capable of observing, it becomes somewhat good at then predicting (assuming those behaviors are predictable).

Unfortunately, machine learning algorithms tend to be “black boxes”; they work, but nobody can really say what the algorithm is doing. It’s a little like a chef “just knowing” when to take the cake out of the oven beacuse they’ve had lots of experience. In that sense there’s already a personalized digital “Approximate Dostoevsky Almanac” that can predict, with some accuracy, what you’re likely to do (and buy), but nobody can read it. Even if, in theory, our brains are predictable, the almanacs we’re writing don’t mean much to those same brains.

I would like to posit the human, free-will game of poker. I am pretty good at it. It requires knowing when to hold them, knowing when to fold them. I’ll stop the lesson there.

However, you need to know the odds. If you simply play by the math (stats), you may do alright, but if you apply your free will, and bluff part of the time, you have a better chance of success (slow playing an ace on the table when you have two in hand, or act like you have two in hand).

The main point is you use your judgement you can mess with someone else’s free will in determining the future depending on the amount to win.

In the fourth paragraph of your response in the last few lines, it looks like some shoe laces tangled in the writing. “and quickly swamp any attempt to accurate the predict the future behavior of the system.” When you say “to accurate the predict the future” I think ou meant to say “to accurately predict the future”, taking out the first “the” and changing accurate an adjective into accurately an adverb.

Always interesting! Thank you!

@A Helper Of Grammar And Spelling

Thank you very much!

As a data scientist at one of those firms that likes to use data to sell you things, I can attest that predicting human behavior is indeed very possible and profitable. However, as the very next paragraph states, very tiny errors can accumulate to useless predictions: and the data quality at these large firms is, while in some places spookily accurate, more often than not wrong or at least slightly off. So the predictions are useful, but it’s not too hard to cover your tracks enough to make it a lot harder for them to target you.

But even if we had perfect data about you and infinite computing power, our models wouldn’t be able to predict everything you would do _unless_ the models have as much freedom as the human brain.

That is, in order for such an almanac to be able to predict everything a human might be able to do, it must first have the power to enumerate all the actions that a human might be able to do. If the almanac doesn’t know about eating, for example, it doesn’t matter how much it knows about the rest of the universe: it will never be able to predict the behavior of eating.

And so very quickly you end up with needing to build a model that is _at least_ as complicated as the human mind. It has to be more complicated, of course, if you want it to be able to do more than predict a single human’s behavior.

But, practically, big firms don’t need or care to know everything you are going to do. They just want to know how to get your money (usually by encouraging you to buy things). And for that, models can be quite simple (by comparison to the brain) indeed.

All that being said, to answer the question, yes it is possible to create an almanac that predicts everything a person will do. The universe (the whole thing) is doing it right now. That is, there’s this thing called the past. Now you might say that it’s not fair to call that a prediction since we already know what will happen, and you’d be right, but prediction models are trained and validated on data where the events/outcomes are known. And when it comes to validation: the model doesn’t know that the events are already known. So as far as the “almanac” is concerned, one could hypothetically use the whole of the past as the training data (or even the model itself). The question then is, for events in the future, does such a model underfit (not have enough predictive power) or overfit (predict the past so well that it sucks at predicting the future b/c it is just regurgitating the past). Or, is the arrow of time in this universe just an illusion to those of us stuck in it, therefore the whole universe is actually a constant when viewed from the “outside”, and therefore the universe itself is as good as a mode as you’ll ever need? In any case, none of that gets us closer to something useful that you or I could use.

As for the philosophical idea of free will, I have to say that we like to wrap up free will in the physics of things, but to be perfectly honest, I don’t think that physics holds the answer. We can still use logic to reason about it, but I don’t think science can truly answer the question. Whether the universe is governed by deterministic or non-deterministic rules, at the end of the day, your will is not separate from those rules. Sure, if you believe your “self” is separate from the universe then by all means believe however you wish, but that’s beyond the realm of what we can really discuss in a logical fashion. So why does that matter? Consider that you truly have free will. If you do, then you must be able to decide to do anything you want, whenever you want (your body might limit you, but it’s the deciding in the mind that’s important for this discussion).

Now, that’s all well and good, that you can decide what you want, but _why_ did you decide it? Say you decide to eat a bar of chocolate and that is evidence for your free will. Okay, so why did you decide to eat a bar of chocolate?

If it is because you like chocolate, then, if you truly have free will, you must be able to decide to _not_ like chocolate. You could argue that this is unfair, as your preference is decided by your body, not your mind. But if that is true, then the question has to be asked: how much of your will is governed by parameters internal to your mind, and how much of it is governed by your body? Your mind is, of course, part of your body, so the line cannot be drawn.

Put more abstractly: let’s say you want to change something (it doesn’t matter what that something is). In effect, you are changing your will (you go from a state of accepting something as it is to a state where you are willing yourself to change that something). What motivates that change in state?

If it is your will that motivates the change in state, then what is motivating your will to motivate the change in state? And now we can go in this spiral forever.

And that brings us back to the core of the issue: your mind is governed by the rules of how this universe works. It doesn’t matter that the rules are deterministic or non-deterministic: the rules were not our choice, and neither was our genetics, and we, at best, have only limited control over our nurture (in that whole nature vs nurture debate). So no matter what choices you make, you are still making them as a function of the inner workings of your mind, which are governed by the rules of this universe.

Let’s say you could go back before you were born and change your personality with the objective of arriving at a personality in which you have total free will despite whatever rules of physics are in play (so this is a universe-agnostic thought experiment, so long as said universe is logical).

Well here’s the problem: how would you make that choice of what to change? And more importantly, who would be making that choice? “Well”, you say, “it’s me who is making the change!”

But it’s you as you are today (or sometime in the past, or sometime in the future, it doesn’t matter)! It’s a personality you did not choose that is making the choice! So no matter what change in your own personality you decide to make, that decision is ultimately a function of your current personality. Even if you decide to throw dice and the universe happens to be gracious enough to be nondeterministic, the very decision to throw dice is a result of your current personality. And if you leave the decision up to someone else then you end up right back where you started: with a set of genetics or place in history that you didn’t pick. We can change the objective (or get rid of it altogether) and we are still left with the same problem.

TL;DR: you may have free will, on the surface. But you don’t have control over your will itself, you can’t will the will. Supposing you could, what would you do with it? And who would be doing what with it? It’s like your tongue trying to taste itself, or your eyes trying to see themself, or the universe trying to contain itself. And this is why the underlying physics doesn’t really matter for the problem of free will. Nondeterminism might make it harder, even impossible, to make predictions about what people will do. But that doesn’t mean the people are suddenly able to command the rules of physics within their own minds to be able to make any kind of decision they want. And even if it did, how would such a person make the decisions to change the rules themselves?

But you can still theoretically do it, right?

@Gol

Theoretically, yes! In order to create a system that perfectly predicts the actions of an arbitrary number of humans (or birds, or crabs, or Xenomorphs), you must simply create a universe that contains those things.

That universe is your prediction system, your ‘almanac’, and it will perfectly and accurately predict the actions of every single thing inside it.

Sadly, it will not be of much use to you, who is -outside- that universe, and thus cannot be measured and predicted by it.

There are several issues here

1) Whether or not humans are completely described by the laws of physics. That is, is there nothing beyond the material reality?**

2) Whether or not these laws of physics are deterministic.

3) Depending on the answer to (2) – what does that say about predicting human behavior.

If the answer to (2) is yes; that we live in a clockwork type universe, then the answer to (3) is, surprisingly, not really! Even if a computer with infinite precision, we would still need perfect accuracy. So in practicality no.

But the answer to (2) turned out to actually be no. That is, as we currently understand it, there is genuine randomness baked into the fundamental laws of the universe. There is therefore no possibility of prediction.

**On a certain level this is imprecise: if you allow for the existence of things like God, a soul, or whatever; i.e. things which aren’t bound by the “laws of physics” – that is nonsensical because they still exist – so they are still “natural” – and they would still obey some laws. Nonetheless, it’s not immediately clear that you couldn’t describe a “natural world” which obeys laws of physics and a “supernatural world” which can intervene in the natural world but doesn’t obey any physical laws….

Dear colleagues,

What do you think about the real experiments described in the

link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xX14NK8GrDY&ab_channel=PeterAxe ?

Looking forward to your comments.

There will always be some person whose actions the the model can not predict and that is the person reading the predictions. He can always choose to spite the model and do differently.

People are not machines. They have purposes and can innovate. Could any model have predicted that Einstein would come up with his theories? Then the model would be smarter than Einstein, since it would already have invented the theories!