The original question was: How come the length of the repetend for some fractions (e.g. having a prime number p as a denominator) is equal to p-1?

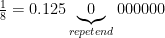

Physicist: The question is about the fact that if you type a fraction into a calculator, the decimal that comes out repeats. But it repeats in a very particular way. For example,

7 is a prime number and (you can check this) all fractions with a denominator of 7 repeat every 7-1=6 digits (even if it does so trivially with “000000”). The trick to understanding why this happens in general is to look really hard at how division works. That is to say: just do long division and see what happens.

When we say that  , what we mean is

, what we mean is  . With that in mind, here’s why

. With that in mind, here’s why  .

.

![\begin{array}{ll} \frac{1}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10}\frac{10}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{1}{10}\frac{3}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{1}{10^2}\frac{30}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{4}{10^2} + \frac{1}{10^2}\frac{2}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{4}{10^2} + \frac{1}{10^3}\frac{20}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{4}{10^2} + \frac{2}{10^3} + \frac{1}{10^3}\frac{6}{7} \\[2mm] \end{array} \begin{array}{ll} \frac{1}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10}\frac{10}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{1}{10}\frac{3}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{1}{10^2}\frac{30}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{4}{10^2} + \frac{1}{10^2}\frac{2}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{4}{10^2} + \frac{1}{10^3}\frac{20}{7} \\[2mm] = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{4}{10^2} + \frac{2}{10^3} + \frac{1}{10^3}\frac{6}{7} \\[2mm] \end{array}](//s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bll%7D++%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B7%7D+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3D+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%5Cfrac%7B10%7D%7B7%7D+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3D+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%5Cfrac%7B3%7D%7B7%7D+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3D+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%5Cfrac%7B30%7D%7B7%7D+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3D+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B10%5E2%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%5Cfrac%7B2%7D%7B7%7D+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3D+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B10%5E2%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%5Cfrac%7B20%7D%7B7%7D+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3D+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B10%5E2%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B2%7D%7B10%5E3%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%5Cfrac%7B6%7D%7B7%7D+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000&s=0)

and so on forever. You’ll notice that the same thing is done to the numerator over and over: multiply by 10, divide by 7, the quotient is the digit in the decimal and the remainder gets carried to the next step, multiply by 10, …. The remainder that gets carried from one step to the next is just ![\left[10^k\right]_7 \left[10^k\right]_7](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5B10%5Ek%5Cright%5D_7&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) .

.

Quick aside: If you’re not familiar with modular arithmetic, there’s an old post here that has lots of examples (and a shallower learning curve). The bracket notation I’m using here isn’t standard, just better. “[4]3” should be read “4 mod 3”. And because the remainder of 4 divided by 3 and the remainder of 1 divided by 3 are both 1, we can say “[4]3=[1]3“.

![\begin{array}{l|l}\frac{1}{7}&[1]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}\frac{10}{7}&[10]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}+\frac{1}{10}\frac{3}{7}&[10]_7=[3]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}+\frac{1}{10^2}\frac{30}{7}&[10^2]_7=[30]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}+\frac{4}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^2}\frac{2}{7}&[10^2]_7=[2]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}+\frac{4}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^3}\frac{20}{7}&[10^3]_7=[20]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}+\frac{4}{10^2}+\frac{2}{10^3}+\frac{1}{10^3}\frac{6}{7}&[10^3]_7=[6]_7\\[2mm] \end{array} \begin{array}{l|l}\frac{1}{7}&[1]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}\frac{10}{7}&[10]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}+\frac{1}{10}\frac{3}{7}&[10]_7=[3]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}+\frac{1}{10^2}\frac{30}{7}&[10^2]_7=[30]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}+\frac{4}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^2}\frac{2}{7}&[10^2]_7=[2]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}+\frac{4}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^3}\frac{20}{7}&[10^3]_7=[20]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{1}{10}+\frac{4}{10^2}+\frac{2}{10^3}+\frac{1}{10^3}\frac{6}{7}&[10^3]_7=[6]_7\\[2mm] \end{array}](//s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bl%7Cl%7D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B1%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%5Cfrac%7B10%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B10%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%5Cfrac%7B3%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B10%5D_7%3D%5B3%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%5Cfrac%7B30%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B10%5E2%5D_7%3D%5B30%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%5Cfrac%7B2%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B10%5E2%5D_7%3D%5B2%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%5Cfrac%7B20%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B10%5E3%5D_7%3D%5B20%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B2%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%5Cfrac%7B6%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B10%5E3%5D_7%3D%5B6%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000&s=0)

These aren’t the numbers that end up in the decimal expansion, they’re the remainder left over when you stop calculating the decimal expansion at any point. What’s important about these numbers is that they each determine the next number in the decimal expansion, and they repeat every 6.

![\begin{array}{ll} [1]_7=1\\[2mm] [10]_7=3\\[2mm] [10^2]=2\\[2mm] [10^3]=6\\[2mm] [10^4]=4\\[2mm] [10^5]=5\\[2mm] [10^6]=1\end{array} \begin{array}{ll} [1]_7=1\\[2mm] [10]_7=3\\[2mm] [10^2]=2\\[2mm] [10^3]=6\\[2mm] [10^4]=4\\[2mm] [10^5]=5\\[2mm] [10^6]=1\end{array}](//s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bll%7D++%5B1%5D_7%3D1%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%5B10%5D_7%3D3%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%5B10%5E2%5D%3D2%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%5B10%5E3%5D%3D6%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%5B10%5E4%5D%3D4%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%5B10%5E5%5D%3D5%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%5B10%5E6%5D%3D1%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000&s=0)

After this it repeats because, for example, ![[10^9]_7 = [10^3\cdot10^6]_7 = [10^3\cdot1]_7 = [10^3]_7 [10^9]_7 = [10^3\cdot10^6]_7 = [10^3\cdot1]_7 = [10^3]_7](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B10%5E9%5D_7+%3D+%5B10%5E3%5Ccdot10%5E6%5D_7+%3D+%5B10%5E3%5Ccdot1%5D_7+%3D+%5B10%5E3%5D_7&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) . If you want to change the numerator to, say, 4, then very little changes:

. If you want to change the numerator to, say, 4, then very little changes:

![\begin{array}{l|l}\frac{4}{7}&[4]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{1}{10}\frac{5}{7}&[4\cdot10]_7=[5]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{7}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^2}\frac{1}{7}&[4\cdot10^2]_7=[1]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{7}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^3}+\frac{1}{10^3}\frac{3}{7}&[4\cdot10^3]_7=[3]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{7}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^3}+\frac{4}{10^4}+\frac{1}{10^4}\frac{2}{7}&[4\cdot10^4]_7=[2]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{7}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^3}+\frac{4}{10^4}+\frac{2}{10^5}+\frac{1}{10^5}\frac{6}{7}&[4\cdot10^5]_7=[6]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{7}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^3}+\frac{4}{10^4}+\frac{2}{10^5}+\frac{8}{10^6}+\frac{1}{10^6}\frac{4}{7}&[4\cdot10^6]_7=[4]_7\\[2mm]\end{array} \begin{array}{l|l}\frac{4}{7}&[4]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{1}{10}\frac{5}{7}&[4\cdot10]_7=[5]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{7}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^2}\frac{1}{7}&[4\cdot10^2]_7=[1]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{7}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^3}+\frac{1}{10^3}\frac{3}{7}&[4\cdot10^3]_7=[3]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{7}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^3}+\frac{4}{10^4}+\frac{1}{10^4}\frac{2}{7}&[4\cdot10^4]_7=[2]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{7}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^3}+\frac{4}{10^4}+\frac{2}{10^5}+\frac{1}{10^5}\frac{6}{7}&[4\cdot10^5]_7=[6]_7\\[2mm]=\frac{5}{10}+\frac{7}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^3}+\frac{4}{10^4}+\frac{2}{10^5}+\frac{8}{10^6}+\frac{1}{10^6}\frac{4}{7}&[4\cdot10^6]_7=[4]_7\\[2mm]\end{array}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bl%7Cl%7D%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B4%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B5%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%5Cfrac%7B5%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B4%5Ccdot10%5D_7%3D%5B5%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B5%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B7%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B4%5Ccdot10%5E2%5D_7%3D%5B1%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B5%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B7%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%5Cfrac%7B3%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B4%5Ccdot10%5E3%5D_7%3D%5B3%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B5%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B7%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B10%5E4%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E4%7D%5Cfrac%7B2%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B4%5Ccdot10%5E4%5D_7%3D%5B2%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B5%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B7%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B10%5E4%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B2%7D%7B10%5E5%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E5%7D%5Cfrac%7B6%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B4%5Ccdot10%5E5%5D_7%3D%5B6%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B5%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B7%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B10%5E4%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B2%7D%7B10%5E5%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B8%7D%7B10%5E6%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E6%7D%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B7%7D%26%5B4%5Ccdot10%5E6%5D_7%3D%5B4%5D_7%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0)

So the important bit to look at is the remainder after each step. More generally, the question of why a decimal expansion repeats can now be seen as the question of why ![[10^k]_P [10^k]_P](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B10%5Ek%5D_P&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) repeats every P-1, when P is prime. For example, for

repeats every P-1, when P is prime. For example, for  we’d be looking at

we’d be looking at ![[2\cdot10^k]_3 [2\cdot10^k]_3](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B2%5Ccdot10%5Ek%5D_3&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) and for

and for  we’d be looking at

we’d be looking at ![[30\cdot10^k]_{11} [30\cdot10^k]_{11}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B30%5Ccdot10%5Ek%5D_%7B11%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) . The “10” comes from the fact that we use a base 10 number system, but that’s not written in stone either (much love to my base 20 Mayan brothers and sisters. Biix a beele’ex, y’all?).

. The “10” comes from the fact that we use a base 10 number system, but that’s not written in stone either (much love to my base 20 Mayan brothers and sisters. Biix a beele’ex, y’all?).

It turns out that when the number in the denominator, M, is coprime to 10 (has no factors of 2 or 5), then the numbers generated by successive powers of ten (mod M) are always also coprime to M. In the examples above M=7 and the powers of 10 generated {1,2,3,4,5,6} (in a scrambled order). The number of numbers less than M that are coprime to M (have no factors in common with M) is denoted by ϕ(M), the “Euler phi of M”. For example, ϕ(9)=6, since {1,2,4,5,7,8} are all coprime to 9. For a prime number, P, every number less than that number is coprime to it, so ϕ(P)=P-1.

When you find the decimal expansion of a fraction, you’re calculating successive powers of ten and taking the mod. As long as 10 is coprime to the denominator, this generates numbers that are also coprime to the denominator. If the denominator is prime, there are P-1 of these. More generally, if the denominator is M, there are ϕ(M) of them. For example,  , which repeats every 12 because ϕ(21)=12. It also repeats every 6, but that doesn’t change the “every 12” thing.

, which repeats every 12 because ϕ(21)=12. It also repeats every 6, but that doesn’t change the “every 12” thing.

Why the powers of ten must either hit every one of the ϕ(M) coprime numbers, or some fraction of ϕ(M) ( , or

, or  , or …), thus forcing the decimal to repeat every ϕ(M) will be in the answer gravy below.

, or …), thus forcing the decimal to repeat every ϕ(M) will be in the answer gravy below.

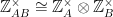

Answer Gravy: Here’s where the number theory steps in. The best way to describe, in extreme generalization, what’s going on is to use “groups“. A group is a set of things and an operation, with four properties: closure, inverses, identity, and associativity.

In this case the set of numbers we’re looking at are the numbers coprime to M, mod M. If M=7, then our group is {1,2,3,4,5,6} with multiplication as the operator. This group is denoted “ “.

“.

The numbers coprime to M are “closed” under multiplication, which means that if  and

and  , then

, then  . This is because if you multiply two numbers with no factors in common with M, then you’ll get a new number with no factors in common with M. For example,

. This is because if you multiply two numbers with no factors in common with M, then you’ll get a new number with no factors in common with M. For example, ![[3\cdot4]_7=[12]_7=[5]_7 [3\cdot4]_7=[12]_7=[5]_7](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B3%5Ccdot4%5D_7%3D%5B12%5D_7%3D%5B5%5D_7&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) . No 7’s in sight (other than the mod, which is 7).

. No 7’s in sight (other than the mod, which is 7).

The numbers coprime to M have inverses. This is a consequence of Bézout’s lemma (proof in the link), which says that if a and M are coprime, then there are integers x and y such that xa+yM=1, with x coprime to M and y coprime to a. Writing that using modular math, if a and M are coprime, then there exists an x such that ![[xa]_M=[1]_M [xa]_M=[1]_M](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Bxa%5D_M%3D%5B1%5D_M&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) . For example,

. For example, ![[1\cdot1]_7=[1]_7 [1\cdot1]_7=[1]_7](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B1%5Ccdot1%5D_7%3D%5B1%5D_7&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) ,

, ![[2\cdot4]_7=[1]_7 [2\cdot4]_7=[1]_7](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B2%5Ccdot4%5D_7%3D%5B1%5D_7&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) ,

, ![[3\cdot5]_7=[1]_7 [3\cdot5]_7=[1]_7](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B3%5Ccdot5%5D_7%3D%5B1%5D_7&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , and

, and ![[6\cdot6]_7=[1]_7 [6\cdot6]_7=[1]_7](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B6%5Ccdot6%5D_7%3D%5B1%5D_7&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) . Here we’d write

. Here we’d write ![[3^{-1}]_7=[5]_7 [3^{-1}]_7=[5]_7](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B3%5E%7B-1%7D%5D_7%3D%5B5%5D_7&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , which means “the inverse of 3 is 5”.

, which means “the inverse of 3 is 5”.

The numbers coprime to M have an identity element. The identity element is the thing that doesn’t change any of the other elements. In this case the identity is 1, because  in general. 1 is coprime to everything (it has no factors), so 1 is always in

in general. 1 is coprime to everything (it has no factors), so 1 is always in  regardless of what M is.

regardless of what M is.

Finally, the numbers coprime to M are associative, which means that (ab)c=a(bc). This is because multiplication is associative. No biggy.

So  , the set of numbers (mod M) coprime to M, form a group under multiplication. Exciting stuff.

, the set of numbers (mod M) coprime to M, form a group under multiplication. Exciting stuff.

But what we’re really interested in are “cyclic subgroups”. “Cyclic groups” are generated by the same number raised to higher and higher powers. For example in mod 7, {31,32,33,34,35,36}={3,2,6,4,5,1} is a cyclic group. In fact, this is  . On the other hand, {21,22,23}={2,4,1} is a cyclic subgroup of

. On the other hand, {21,22,23}={2,4,1} is a cyclic subgroup of  . A subgroup has all of the properties of a group itself (closure, inverses, identity, and associativity), but it’s a subset of a larger group.

. A subgroup has all of the properties of a group itself (closure, inverses, identity, and associativity), but it’s a subset of a larger group.

In general, {a1,a2,…,ar} is always a group, and often is a subgroup. The “r” there is called the “order of the group”, and it is the smallest number such that ![[a^r]_M=[1]_M [a^r]_M=[1]_M](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba%5Er%5D_M%3D%5B1%5D_M&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) .

.

Cyclic groups are closed because ![[a^x\cdot a^y]_M=[a^{x+y}]_M [a^x\cdot a^y]_M=[a^{x+y}]_M](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba%5Ex%5Ccdot+a%5Ey%5D_M%3D%5Ba%5E%7Bx%2By%7D%5D_M&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) .

.

Cyclic groups contain the identity. There are only a finite number of elements in the full group,  , so eventually different powers of a will be the same. Therefore,

, so eventually different powers of a will be the same. Therefore,

![\begin{array}{ll} [a^x]_M=[a^y]_M \\[2mm] \Rightarrow[a^x]_M=[a^xa^{y-x}]_M \\[2mm] \Rightarrow[(a^x)^{-1}a^x]_M=[(a^x)^{-1}a^xa^{y-x}]_M \\[2mm] \Rightarrow[1]_M=[a^{y-x}]_M \end{array} \begin{array}{ll} [a^x]_M=[a^y]_M \\[2mm] \Rightarrow[a^x]_M=[a^xa^{y-x}]_M \\[2mm] \Rightarrow[(a^x)^{-1}a^x]_M=[(a^x)^{-1}a^xa^{y-x}]_M \\[2mm] \Rightarrow[1]_M=[a^{y-x}]_M \end{array}](//s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bll%7D++++%5Ba%5Ex%5D_M%3D%5Ba%5Ey%5D_M+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%5CRightarrow%5Ba%5Ex%5D_M%3D%5Ba%5Exa%5E%7By-x%7D%5D_M+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%5CRightarrow%5B%28a%5Ex%29%5E%7B-1%7Da%5Ex%5D_M%3D%5B%28a%5Ex%29%5E%7B-1%7Da%5Exa%5E%7By-x%7D%5D_M+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%5CRightarrow%5B1%5D_M%3D%5Ba%5E%7By-x%7D%5D_M++++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000&s=0)

That is to say, if you get the same value for different powers, then the difference between those powers is the identity. For example, ![[3^2]_7=[2]_7=[3^8]_7 [3^2]_7=[2]_7=[3^8]_7](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B3%5E2%5D_7%3D%5B2%5D_7%3D%5B3%5E8%5D_7&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) and it’s no coincidence that

and it’s no coincidence that ![[3^{8-2}]_7=[3^6]_7=[1]_7 [3^{8-2}]_7=[3^6]_7=[1]_7](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B3%5E%7B8-2%7D%5D_7%3D%5B3%5E6%5D_7%3D%5B1%5D_7&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) .

.

Cyclic groups contain inverses. There is an r such that ![[a^r]_M=[1]_M [a^r]_M=[1]_M](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba%5Er%5D_M%3D%5B1%5D_M&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) . It follows that

. It follows that ![[ba^x]_M=[1]_M\Rightarrow[ba^x]_M=[a^r]_M\Rightarrow[b]_M=[a^{r-x}]_M [ba^x]_M=[1]_M\Rightarrow[ba^x]_M=[a^r]_M\Rightarrow[b]_M=[a^{r-x}]_M](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Bba%5Ex%5D_M%3D%5B1%5D_M%5CRightarrow%5Bba%5Ex%5D_M%3D%5Ba%5Er%5D_M%5CRightarrow%5Bb%5D_M%3D%5Ba%5E%7Br-x%7D%5D_M&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) . So,

. So, ![[\left(a^x\right)^{-1}]_M=[a^{r-x}]_M [\left(a^x\right)^{-1}]_M=[a^{r-x}]_M](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Cleft%28a%5Ex%5Cright%29%5E%7B-1%7D%5D_M%3D%5Ba%5E%7Br-x%7D%5D_M&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) .

.

And cyclic subgroups have associativity. Yet again: no biggy, that’s just how multiplication works.

It turns out that the number of elements in a subgroup always divides the number of elements in the group as a whole. For example,  ={1,2,3,4,5,6} is a group with 6 elements, and the cyclic subgroup generated by 2, {1,2,4}, has 3 elements. But check it: 3 divides 6. This is Lagrange’s Theorem. It comes about because cosets (which you get by multiplying every element in a subgroup by the same number) are always the same size and are always distinct. For example (again in mod 7),

={1,2,3,4,5,6} is a group with 6 elements, and the cyclic subgroup generated by 2, {1,2,4}, has 3 elements. But check it: 3 divides 6. This is Lagrange’s Theorem. It comes about because cosets (which you get by multiplying every element in a subgroup by the same number) are always the same size and are always distinct. For example (again in mod 7),

The cosets here are {1,2,4} and {3,5,6}. They’re the same size, they’re distinct, and together they hit every element in  . The cosets of any given subgroup are always the same size as the subgroup, always distinct (no shared elements), and always hit every element of the larger group. This means that if the subgroup has S elements, there are C cosets, and the group as a whole has G elements, then SD=G. Therefore, in general, the number of elements in a subgroup divides the number of elements in a whole group.

. The cosets of any given subgroup are always the same size as the subgroup, always distinct (no shared elements), and always hit every element of the larger group. This means that if the subgroup has S elements, there are C cosets, and the group as a whole has G elements, then SD=G. Therefore, in general, the number of elements in a subgroup divides the number of elements in a whole group.

To sum up:

In order to calculate a decimal expansion (in base 10) you need to raise 10 to higher and higher powers and divide by the denominator, M. The quotient is the next digit in the decimal and the remainder is what’s carried on to the next step. The remainder is what the “mod” operation yields. This leads us to consider the group of  which is the multiplication mod M group of numbers coprime to M (the not-coprime-case will be considered in a damn minute).

which is the multiplication mod M group of numbers coprime to M (the not-coprime-case will be considered in a damn minute).  has exactly ϕ(M) elements. The powers of 10 form a “cyclic subgroup”. The number of numbers in this cyclic subgroup must divide ϕ(M), by Lagrange’s theorem.

has exactly ϕ(M) elements. The powers of 10 form a “cyclic subgroup”. The number of numbers in this cyclic subgroup must divide ϕ(M), by Lagrange’s theorem.

If P is prime, then ϕ(P)=P-1, and therefore if the denominator is prime the length of the cycle of digits in the decimal expansion (which is dictated by the cyclic subgroup generated by 10) must divide P-1. That is, the decimal repeats every P-1, but it might also repeat every  or

or  or whatever. You can also calculate ϕ(M) for M not prime, and the same idea holds.

or whatever. You can also calculate ϕ(M) for M not prime, and the same idea holds.

Deep Gravy:

Finally, if the denominator is not coprime to 10 (e.g., 3/5, 1/2, 1/14, 71/15, etc.), then things get a little screwed up. If the denominator is nothing but factors of 10, then the decimal is always finite. For example,  .

.

![\begin{array}{l|l} \frac{1}{8}&[1]_8\\[2mm] =\frac{1}{10}+\frac{1}{10}\frac{2}{8}&[10]_8=[2]_8\\[2mm] =\frac{1}{10}+\frac{2}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^2}\frac{4}{8}&[10^2]_8=[4]_8\\[2mm] =\frac{1}{10}+\frac{2}{10^2}+\frac{5}{10^3}&[10^3]_8=[0]_8\\[2mm] \end{array} \begin{array}{l|l} \frac{1}{8}&[1]_8\\[2mm] =\frac{1}{10}+\frac{1}{10}\frac{2}{8}&[10]_8=[2]_8\\[2mm] =\frac{1}{10}+\frac{2}{10^2}+\frac{1}{10^2}\frac{4}{8}&[10^2]_8=[4]_8\\[2mm] =\frac{1}{10}+\frac{2}{10^2}+\frac{5}{10^3}&[10^3]_8=[0]_8\\[2mm] \end{array}](//s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bl%7Cl%7D++++%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B8%7D%26%5B1%5D_8%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%5Cfrac%7B2%7D%7B8%7D%26%5B10%5D_8%3D%5B2%5D_8%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B2%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%5Cfrac%7B4%7D%7B8%7D%26%5B10%5E2%5D_8%3D%5B4%5D_8%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B10%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B2%7D%7B10%5E2%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B5%7D%7B10%5E3%7D%26%5B10%5E3%5D_8%3D%5B0%5D_8%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000&s=0)

In general, if the denominator has powers of 2 or 5, then the resulting decimal will be a little messy for the first few digits (equal to the higher of the two powers, for example 8=23) and after that will follow the rules for the part of the denominator coprime to 10. For example,  . So, we can expect that after two digits the decimal expansion will settle into a nice six-digit repetend (because ϕ(7)=6).

. So, we can expect that after two digits the decimal expansion will settle into a nice six-digit repetend (because ϕ(7)=6).

Fortunately, the system works:

This can be understood by looking at the powers of ten for each of the factors of the denominator independently. If A and B are coprime, then  . This is an isomorphism that works because of the Chinese Remainder Theorem. So, a question about the powers of 10 mod 28 can be explored in terms of the powers of 10 mod 4 and mod 7.

. This is an isomorphism that works because of the Chinese Remainder Theorem. So, a question about the powers of 10 mod 28 can be explored in terms of the powers of 10 mod 4 and mod 7.

![\begin{array}{l|l} [10]_{28}=[10]_{28} & \left([10]_{4},[10]_{7}\right) = \left([2]_{4},[3]_{7}\right) \\[2mm] [10^2]_{28}=[16]_{28} & \left([10^2]_{4},[10^2]_{7}\right) = \left([0]_{4},[2]_{7}\right) \\[2mm] [10]_{28}=[10]_{28} & \left([10]_{4},[10]_{7}\right) = \left([0]_{4},[3]_{7}\right) \\[2mm] [10^3]_{28}=[20]_{28} & \left([10^3]_{4},[10^3]_{7}\right) = \left([0]_{4},[6]_{7}\right) \\[2mm] \end{array} \begin{array}{l|l} [10]_{28}=[10]_{28} & \left([10]_{4},[10]_{7}\right) = \left([2]_{4},[3]_{7}\right) \\[2mm] [10^2]_{28}=[16]_{28} & \left([10^2]_{4},[10^2]_{7}\right) = \left([0]_{4},[2]_{7}\right) \\[2mm] [10]_{28}=[10]_{28} & \left([10]_{4},[10]_{7}\right) = \left([0]_{4},[3]_{7}\right) \\[2mm] [10^3]_{28}=[20]_{28} & \left([10^3]_{4},[10^3]_{7}\right) = \left([0]_{4},[6]_{7}\right) \\[2mm] \end{array}](//s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bl%7Cl%7D++++%5B10%5D_%7B28%7D%3D%5B10%5D_%7B28%7D+%26+%5Cleft%28%5B10%5D_%7B4%7D%2C%5B10%5D_%7B7%7D%5Cright%29+%3D+%5Cleft%28%5B2%5D_%7B4%7D%2C%5B3%5D_%7B7%7D%5Cright%29+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%5B10%5E2%5D_%7B28%7D%3D%5B16%5D_%7B28%7D+%26+%5Cleft%28%5B10%5E2%5D_%7B4%7D%2C%5B10%5E2%5D_%7B7%7D%5Cright%29+%3D+%5Cleft%28%5B0%5D_%7B4%7D%2C%5B2%5D_%7B7%7D%5Cright%29+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%5B10%5D_%7B28%7D%3D%5B10%5D_%7B28%7D+%26+%5Cleft%28%5B10%5D_%7B4%7D%2C%5B10%5D_%7B7%7D%5Cright%29+%3D+%5Cleft%28%5B0%5D_%7B4%7D%2C%5B3%5D_%7B7%7D%5Cright%29+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%5B10%5E3%5D_%7B28%7D%3D%5B20%5D_%7B28%7D+%26+%5Cleft%28%5B10%5E3%5D_%7B4%7D%2C%5B10%5E3%5D_%7B7%7D%5Cright%29+%3D+%5Cleft%28%5B0%5D_%7B4%7D%2C%5B6%5D_%7B7%7D%5Cright%29+%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000&s=0)

Once the powers of 10 are a multiple of all of the of 2’s and 5’s in the denominator, they basically disappear and only the coprime component is important.

Numbers are a whole thing. If you can believe it, this was supposed to be a short post.

. Or, for the angle buffs out there, about 0.01 arcseconds. This doesn’t take into account the scattering due to the atmosphere; we can do a little to combat that from the ground, but our techniques aren’t perfect.