Physicist: This famous equation is a little more subtle than it appears. It does provide a relationship between energy and matter, but importantly it does not say that they’re equivalent.

First, it’s worth considering what energy actually is. Rather than being an actual “thing” in the universe, energy is best thought of as an abstract (there’s no such thing as pure energy). Energy takes a heck of a lot of forms: kinetic, chemical, electrical, heat, mechanical, light, sound, nuclear, etc. Each different form has it’s own equation(s). For example, the energy stored in a (not overly) stretched or compressed spring is  and the energy of the heat in an object is

and the energy of the heat in an object is  . Now, these equations are true insofar as they work (like all true equations in physics). However, neither of them are saying what energy is. Energy is a value that we can calculate by adding up the values for all of the various energy equations (for springs, or heat, or whatever).

. Now, these equations are true insofar as they work (like all true equations in physics). However, neither of them are saying what energy is. Energy is a value that we can calculate by adding up the values for all of the various energy equations (for springs, or heat, or whatever).

The useful thing about energy, and the only reason anyone ever even bothered to name it, is that energy is conserved. If you sum up all of the various kinds of energy one moment, then if you check back sometime later you’ll find that you’ll get the same sum. The individual terms may get bigger and smaller, but the total stays the same.

For example, the equation used to describe the energy of a swinging the pendulum is  where the variables are mass, velocity, gravitational acceleration, and height of the pendulum. These two terms, the kinetic and gravitational-potential energies, are included because they change a lot (speed and height change throughout every swing) and because however much one changes, the other absorbs the difference and keeps E fixed. There are more terms that can be included, like the heat of the pendulum or its chemical potential, but since those don’t change much and the whole point of energy is to be constant, those other terms can be ignored (as far as the swinging motion is concerned).

where the variables are mass, velocity, gravitational acceleration, and height of the pendulum. These two terms, the kinetic and gravitational-potential energies, are included because they change a lot (speed and height change throughout every swing) and because however much one changes, the other absorbs the difference and keeps E fixed. There are more terms that can be included, like the heat of the pendulum or its chemical potential, but since those don’t change much and the whole point of energy is to be constant, those other terms can be ignored (as far as the swinging motion is concerned).

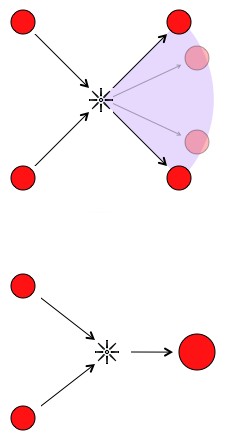

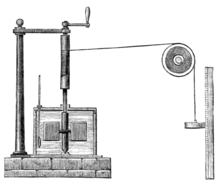

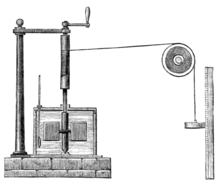

In fact, it isn’t obvious that all of these different forms of energy are related at all. Joule had to do all kinds of goofy experiments to demonstrate that, for example, the sum of gravitational potential energy and thermal energy stays constant. He had to build a machine that turned the energy of an elevated weight into heat, and then was careful to keep track of exactly how much of the first form of energy was lost and how much of the second was gained.

As the weight falls, it turns an agitator that heats the water. Joule’s device couples the gravitational potential of the weight with the thermal energy of the water in a tank. The sum of the two stayed constant.

Enter Einstein. He did a few fancy things in 1905, including figuring out a better way of doing mechanics. Newtonian mechanics had some subtle inconsistencies that modern (1900 modern) science was just beginning to notice. Special relativity helped fixed the heck out of that. Among his other predictions, Einstein suggested (with some solid, consistent-with-experiment, reasoning) that the kinetic energy of a moving object should be  , where the variables here are mass, velocity, and the speed of light (c). This equation has since been tested to hell and back and it works. What’s bizarre about this new equation for kinetic energy is that even when the velocity is zero, the energy is still positive.

, where the variables here are mass, velocity, and the speed of light (c). This equation has since been tested to hell and back and it works. What’s bizarre about this new equation for kinetic energy is that even when the velocity is zero, the energy is still positive.

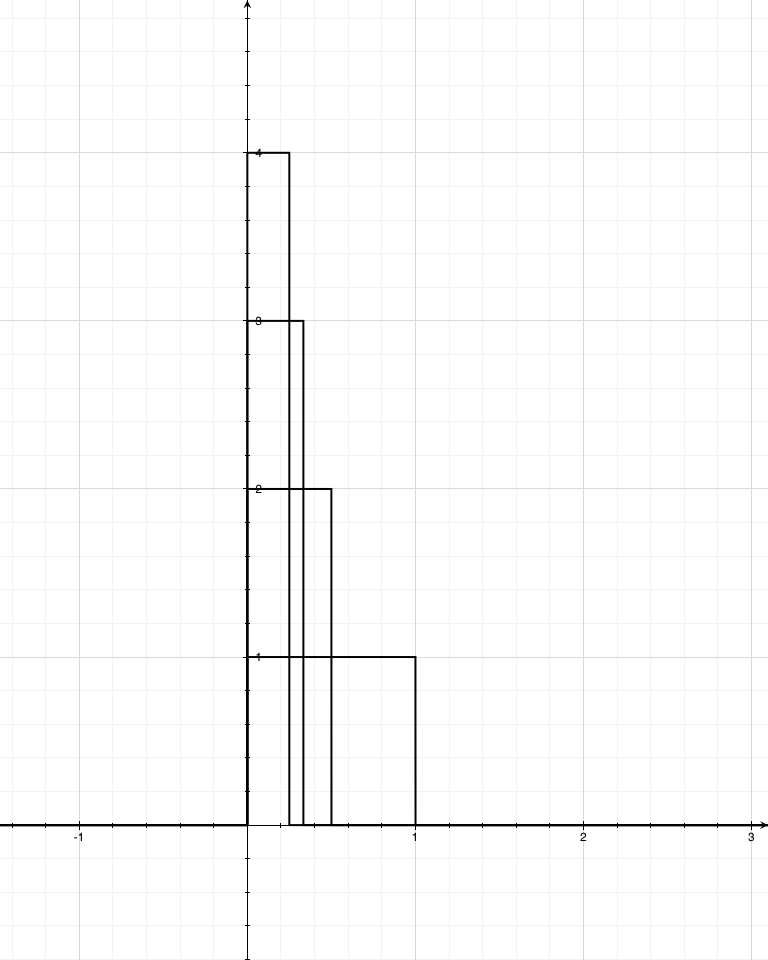

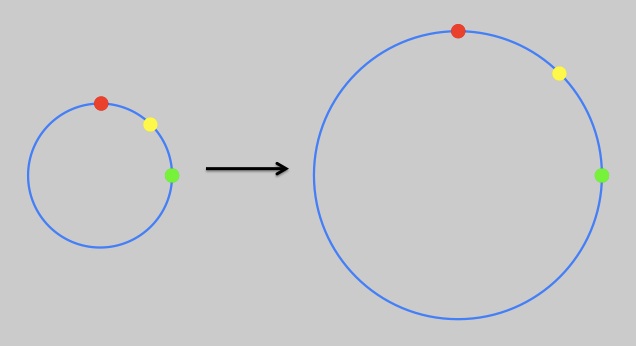

Up to about 40% of light speed (mach 350,000),  is a really good approximation of Einstein’s kinetic energy equation,

is a really good approximation of Einstein’s kinetic energy equation,  . The approximation is good enough that ye natural philosophers of olde can be forgiven for not noticing the tiny error terms. They can also be forgiven for not noticing the mc2 term. Despite being huge compared to all of the other terms, mc2 never changed in those old experiments. Like the chemical potential of the pendulum, the mc2 term wasn’t important for describing anything they were seeing. It’s a little like being on a boat at sea; the tiny rises and falls of the surface are obvious, but the huge distance to the bottom is not.

. The approximation is good enough that ye natural philosophers of olde can be forgiven for not noticing the tiny error terms. They can also be forgiven for not noticing the mc2 term. Despite being huge compared to all of the other terms, mc2 never changed in those old experiments. Like the chemical potential of the pendulum, the mc2 term wasn’t important for describing anything they were seeing. It’s a little like being on a boat at sea; the tiny rises and falls of the surface are obvious, but the huge distance to the bottom is not.

So, that was Einstein’s contribution. Before Einstein, the kinetic energy of a completely stationary rock and a missing rock was the same (zero). After Einstein, the kinetic energy of a stationary rock and a missing rock were extremely different (by mc2 in fact). What this means in terms of energy (which is just the sum of a bunch of different terms that always stays the same) is that “removing an object” now violates the conservation of energy. E=mc2 is very non-specific and at the time it was written: not super helpful. It merely implies that if matter were to disappear, you’d need a certain amount of some other kind of energy to take its place (wound springs, books higher on shelves, warmer tea, some other kind); and in order for new matter to appear, a prescribed amount of energy must also disappear. Not in any profound way, but in a “when the pendulum swings up, it also slows down” sort of way. Einstein also didn’t suggest any method for matter to appear or disappear (that came later). So, energy is a sort of strict economy (total never changes) with many different currencies (types of energy). Einstein showed that matter needed to be included in that “economy”, and that some things in physics are simpler if it is.

While it is true that the amount of mass in a nuclear weapon decreases during detonation, that’s also true of every explosive. For that mater, it’s true of everything that releases energy in any form. When you drain a battery it literally weighs a little less because of the loss of chemical energy. The total difference for a good D-battery is about 0.015 picograms, which is tough to notice especially when the battery is ten billion times more massive. About the only folks who regularly worry about the fact that energy and matter can be sometimes be exchanged are high-energy physicists.

Cloud chamber tracks like these provided some of the earliest evidence of particle creation and have entertained aged nerds for decades.

As far as a particle physicist is concerned, particles don’t have masses; they have equivalent energies. If you happen to corner one at a party (it’s not hard, because they’re meek), ask them the mass of an electron. They’ll probably say “0.5 mega-electronvolts” which is a unit of energy (the kinetic energy of a single unit of charge accelerated by 500,000 volts). In particle physics, the amount of energy released/sequestered when a particle is annihilated/created is typically more important that the amount that a particle physically weighs (I mean, how hard is it to pick up a particle?). So when particle physicists talk shop, they use energy rather than matter. For those of us unbothered by creation and annihilation, the fact that rest-mass is a term included among many different energy terms is pretty unimportant. Nothing we do or experience day-to-day is affected by the fact that rest-mass has energy. Sure the energy is there, but changing it, getting access to it, or doing anything useful with it is difficult.

The cloud chamber picture is from here, and there’s a video of one in action here.