Physicist: In physical sciences we catalog information gained through observation (“what’s that?”), then a model is created (“I bet it works like this!”), and then we try to disprove that model by using experiments (“if we’re right, then we should see this weird thing happening”). In the physical sciences the aim is to disprove, because proofs are always out of reach. There’s always the possibility that you’re missing something (it’s a big, complicated universe after all).

Mathematics is completely different. In math (and really, only in math) we have the power to prove things. The fact that π never repeats isn’t something that we’ve observed, and it’s not something that’s merely “likely” given that we’ve never observed a repeating pattern in the first several trillion digits we’ve seen so far.

The digits of pi never repeat because it can be proven that π is an irrational number and irrational numbers don’t repeat forever.

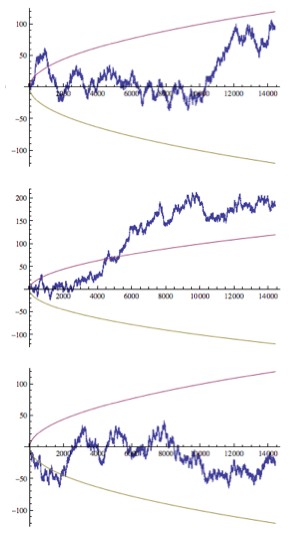

If you write out the decimal expansion of any irrational number (not just π) you’ll find that it never repeats. There’s nothing particularly special about π in that respect. So, proving that π never repeats is just a matter of proving that it can’t be a rational number. Rather than talking vaguely about math, the rest of this post will be a little more direct than the casual reader might normally appreciate. For those of you who just scrolled down the page and threw up a little, here’s a very short argument (not a proof):

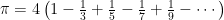

It turns out that  . But this string of numbers includes all of the prime numbers (other than 2) in the denominator, and since there are an infinite number of primes, there should be no common denominator. That means that π is irrational, and that means that π never repeats. The difference between an “argument” and a “proof” is that a proof ends debates, whereas an argument just puts folk more at ease (mathematically speaking). The math-blizzard below is a genuine proof. First,

. But this string of numbers includes all of the prime numbers (other than 2) in the denominator, and since there are an infinite number of primes, there should be no common denominator. That means that π is irrational, and that means that π never repeats. The difference between an “argument” and a “proof” is that a proof ends debates, whereas an argument just puts folk more at ease (mathematically speaking). The math-blizzard below is a genuine proof. First,

Numbers with repeating decimal expansions are always rational.

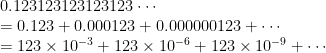

If a number can be written as the D digit number “N” repeating forever, then it can be expressed as  . For example, when N=123 and D=3:

. For example, when N=123 and D=3:

Luckily, this can always be figured out exactly using some very old math tricks. This is just a geometric series, and  . So for example,

. So for example,  .

.

Even if the decimal starts out a little funny, and then settles down into a pattern, it doesn’t make any difference. The “funny part” can be treated as a separate rational number. For example,  . And the sum of any rational numbers is always a rational number, so for example,

. And the sum of any rational numbers is always a rational number, so for example,  .

.

So, if something has a forever-repeating decimal expansion, then it is a rational number. Equivalently, if something is an irrational number, then it does not have a repeating decimal. For example,

√2 is an irrational number

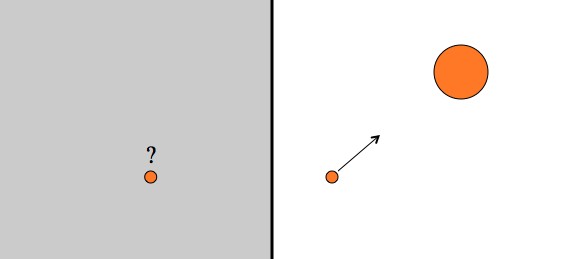

So, in order to prove that a number doesn’t repeat forever, you need to prove that it is irrational. A number is irrational if it cannot be expressed in the form  , where A and B are integers. √2 was the first number shown conclusively to be irrational (about 2500 years ago). The proof of the irrationality of π is a little tricky, so this part is just to convey the flavor of one of these proofs-of-irrationality.

, where A and B are integers. √2 was the first number shown conclusively to be irrational (about 2500 years ago). The proof of the irrationality of π is a little tricky, so this part is just to convey the flavor of one of these proofs-of-irrationality.

Assume that  , and that A and B have no common factors. Then it follows that

, and that A and B have no common factors. Then it follows that  . Therefore, A is an even number since

. Therefore, A is an even number since  has a factor of 2. But if

has a factor of 2. But if  is an integer, then we can write:

is an integer, then we can write:  and therefore

and therefore  . But that means that B is an even number.

. But that means that B is an even number.

This is a contradiction, since we assumed that A and B have no common factors. By the way, if they did have common factors, then we could cancel them out. No biggie.

So, √2 is irrational, and therefore its decimal expansion (√2=1.4142135623730950488016887242096980785696…) never repeats. This isn’t just some experimental observation, it’s an absolute fact. That’s why it’s useful to prove, rather than just observe, that

π is an irrational number

The earliest known proof of this was written in 1761. However, what follows is a much simpler proof written in 1946. Unfortunately, there don’t seem to be any simple, no-calculus proofs floating around, so if you don’t dig calculus and some of the notation from calculus, then you won’t dig this. Here goes:

Assume that  . Now define a function

. Now define a function  , where n is some positive integer, and that excited n, n!, is “n factorial“. No problems so far.

, where n is some positive integer, and that excited n, n!, is “n factorial“. No problems so far.

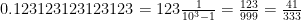

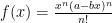

All of the derivatives of  taken at x=0 are integers. This is because

taken at x=0 are integers. This is because  (by the binomial expansion theorem), which means that the kth derivative is

(by the binomial expansion theorem), which means that the kth derivative is

If k<n, then there is no constant term (an x0 term), so  . If n≤k≤2n, then there is a constant term, but

. If n≤k≤2n, then there is a constant term, but  is still an integer. The j=k-n term is the constant term, so:

is still an integer. The j=k-n term is the constant term, so:

![\begin{array}{ll}f^{(k)}(0)=\sum_{j=0}^n a^{n-j}(-b)^j\frac{(n+j)!}{j!(n-j)!(n+j-k)!} 0^{n+j-k}\\[2mm]=a^{2n-k}(-b)^{k-n}\frac{k!}{(k-n)!(2n-k)!0!}\\[2mm]=a^{2n-k}(-b)^{k-n}\frac{k!}{(k-n)!(2n-k)!}\end{array} \begin{array}{ll}f^{(k)}(0)=\sum_{j=0}^n a^{n-j}(-b)^j\frac{(n+j)!}{j!(n-j)!(n+j-k)!} 0^{n+j-k}\\[2mm]=a^{2n-k}(-b)^{k-n}\frac{k!}{(k-n)!(2n-k)!0!}\\[2mm]=a^{2n-k}(-b)^{k-n}\frac{k!}{(k-n)!(2n-k)!}\end{array}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bll%7Df%5E%7B%28k%29%7D%280%29%3D%5Csum_%7Bj%3D0%7D%5En+a%5E%7Bn-j%7D%28-b%29%5Ej%5Cfrac%7B%28n%2Bj%29%21%7D%7Bj%21%28n-j%29%21%28n%2Bj-k%29%21%7D+0%5E%7Bn%2Bj-k%7D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3Da%5E%7B2n-k%7D%28-b%29%5E%7Bk-n%7D%5Cfrac%7Bk%21%7D%7B%28k-n%29%21%282n-k%29%210%21%7D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3Da%5E%7B2n-k%7D%28-b%29%5E%7Bk-n%7D%5Cfrac%7Bk%21%7D%7B%28k-n%29%21%282n-k%29%21%7D%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0)

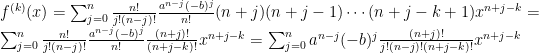

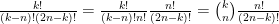

a and b are integers already, so their powers are still integers.  is also an integer since

is also an integer since  . “k choose n” is always an integer, and

. “k choose n” is always an integer, and  , which is just a string of integers multiplied together.

, which is just a string of integers multiplied together.

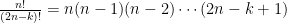

So, the derivatives at zero,  , are all integers. More than that, by symmetry,

, are all integers. More than that, by symmetry,  , are all integers. This is because

, are all integers. This is because

![\begin{array}{ll}f(\pi-x)=f\left(\frac{a}{b}-x\right)\\[2mm]=\frac{\left(\frac{a}{b}-x\right)^n(a-b\left(\frac{a}{b}-x\right))^n}{n!}\\[2mm]=\frac{\left(\frac{a}{b}-x\right)^n(a-\left(a-bx\right))^n}{n!}\\[2mm]=\frac{\left(\frac{a}{b}-x\right)^n(bx)^n}{n!}\\[2mm]=\frac{\left(\frac{1}{b}\right)^n\left(a-bx\right)^n(bx)^n}{n!}\\[2mm]=\frac{\left(a-bx\right)^n x^n}{n!}\end{array} \begin{array}{ll}f(\pi-x)=f\left(\frac{a}{b}-x\right)\\[2mm]=\frac{\left(\frac{a}{b}-x\right)^n(a-b\left(\frac{a}{b}-x\right))^n}{n!}\\[2mm]=\frac{\left(\frac{a}{b}-x\right)^n(a-\left(a-bx\right))^n}{n!}\\[2mm]=\frac{\left(\frac{a}{b}-x\right)^n(bx)^n}{n!}\\[2mm]=\frac{\left(\frac{1}{b}\right)^n\left(a-bx\right)^n(bx)^n}{n!}\\[2mm]=\frac{\left(a-bx\right)^n x^n}{n!}\end{array}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bll%7Df%28%5Cpi-x%29%3Df%5Cleft%28%5Cfrac%7Ba%7D%7Bb%7D-x%5Cright%29%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%28%5Cfrac%7Ba%7D%7Bb%7D-x%5Cright%29%5En%28a-b%5Cleft%28%5Cfrac%7Ba%7D%7Bb%7D-x%5Cright%29%29%5En%7D%7Bn%21%7D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%28%5Cfrac%7Ba%7D%7Bb%7D-x%5Cright%29%5En%28a-%5Cleft%28a-bx%5Cright%29%29%5En%7D%7Bn%21%7D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%28%5Cfrac%7Ba%7D%7Bb%7D-x%5Cright%29%5En%28bx%29%5En%7D%7Bn%21%7D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%28%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7Bb%7D%5Cright%29%5En%5Cleft%28a-bx%5Cright%29%5En%28bx%29%5En%7D%7Bn%21%7D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%28a-bx%5Cright%29%5En+x%5En%7D%7Bn%21%7D%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0)

This is the same function, so the arguments about the derivatives at x=0 being integers also apply to x=π. Keep in mind that it is still being assumed that  .

.

Finally, for k>2n,  , because f(x) is a 2n-degree polynomial (so 2n or more derivatives leaves 0).

, because f(x) is a 2n-degree polynomial (so 2n or more derivatives leaves 0).

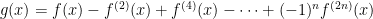

After all that, now construct a new function,  . Notice that g(0) and g(π) are sums of integers, so they are also integers. Using the usual product rule, and the derivative of sines and cosines, it follows that

. Notice that g(0) and g(π) are sums of integers, so they are also integers. Using the usual product rule, and the derivative of sines and cosines, it follows that

![\begin{array}{ll}\frac{d}{dx}\left[g^\prime(x)sin(x) - g(x)cos(x)\right]\\[2mm] = g^{(2)}(x)sin(x)+g^\prime(x)cos(x) - g^{\prime}(x)cos(x)+g(x)sin(x)\\[2mm] =sin(x)\left[g(x)+g^{(2)}(x)\right]\\[2mm] =sin(x)\left[\left(f(x)-f^{(2)}(x)+f^{(4)}(x)-\cdots+(-1)^nf^{(2n)}(x)\right)+\left(f^{(2)}(x)-f^{(4)}(x)+f^{(6)}(x)-\cdots+(-1)^nf^{(2n+2)}(x)\right)\right]\\[2mm] =sin(x)\left[f(x)+\left(f^{(2)}(x)-f^{(2)}(x)\right)+\left(f^{(4)}(x)-f^{(4)}(x)\right)+\cdots+(-1)^n\left(f^{(2n)}(x)-f^{(2n)}(x)\right)+(-1)^nf^{(2n+2)}(x)\right]\\[2mm] =sin(x)\left[f(x)+(-1)^nf^{(2n+2)}(x)\right]\\[2mm] =sin(x)f(x) \end{array} \begin{array}{ll}\frac{d}{dx}\left[g^\prime(x)sin(x) - g(x)cos(x)\right]\\[2mm] = g^{(2)}(x)sin(x)+g^\prime(x)cos(x) - g^{\prime}(x)cos(x)+g(x)sin(x)\\[2mm] =sin(x)\left[g(x)+g^{(2)}(x)\right]\\[2mm] =sin(x)\left[\left(f(x)-f^{(2)}(x)+f^{(4)}(x)-\cdots+(-1)^nf^{(2n)}(x)\right)+\left(f^{(2)}(x)-f^{(4)}(x)+f^{(6)}(x)-\cdots+(-1)^nf^{(2n+2)}(x)\right)\right]\\[2mm] =sin(x)\left[f(x)+\left(f^{(2)}(x)-f^{(2)}(x)\right)+\left(f^{(4)}(x)-f^{(4)}(x)\right)+\cdots+(-1)^n\left(f^{(2n)}(x)-f^{(2n)}(x)\right)+(-1)^nf^{(2n+2)}(x)\right]\\[2mm] =sin(x)\left[f(x)+(-1)^nf^{(2n+2)}(x)\right]\\[2mm] =sin(x)f(x) \end{array}](//s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bll%7D%5Cfrac%7Bd%7D%7Bdx%7D%5Cleft%5Bg%5E%5Cprime%28x%29sin%28x%29+-+g%28x%29cos%28x%29%5Cright%5D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3D+g%5E%7B%282%29%7D%28x%29sin%28x%29%2Bg%5E%5Cprime%28x%29cos%28x%29+-+g%5E%7B%5Cprime%7D%28x%29cos%28x%29%2Bg%28x%29sin%28x%29%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3Dsin%28x%29%5Cleft%5Bg%28x%29%2Bg%5E%7B%282%29%7D%28x%29%5Cright%5D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3Dsin%28x%29%5Cleft%5B%5Cleft%28f%28x%29-f%5E%7B%282%29%7D%28x%29%2Bf%5E%7B%284%29%7D%28x%29-%5Ccdots%2B%28-1%29%5Enf%5E%7B%282n%29%7D%28x%29%5Cright%29%2B%5Cleft%28f%5E%7B%282%29%7D%28x%29-f%5E%7B%284%29%7D%28x%29%2Bf%5E%7B%286%29%7D%28x%29-%5Ccdots%2B%28-1%29%5Enf%5E%7B%282n%2B2%29%7D%28x%29%5Cright%29%5Cright%5D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3Dsin%28x%29%5Cleft%5Bf%28x%29%2B%5Cleft%28f%5E%7B%282%29%7D%28x%29-f%5E%7B%282%29%7D%28x%29%5Cright%29%2B%5Cleft%28f%5E%7B%284%29%7D%28x%29-f%5E%7B%284%29%7D%28x%29%5Cright%29%2B%5Ccdots%2B%28-1%29%5En%5Cleft%28f%5E%7B%282n%29%7D%28x%29-f%5E%7B%282n%29%7D%28x%29%5Cright%29%2B%28-1%29%5Enf%5E%7B%282n%2B2%29%7D%28x%29%5Cright%5D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3Dsin%28x%29%5Cleft%5Bf%28x%29%2B%28-1%29%5Enf%5E%7B%282n%2B2%29%7D%28x%29%5Cright%5D%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D++%3Dsin%28x%29f%28x%29++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000&s=0)

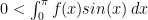

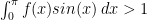

f(x) is positive between 0 and π, since  when

when  . Since sin(x)>0 when 0<x<π as well, it follows that

. Since sin(x)>0 when 0<x<π as well, it follows that  . Finally, using the fundamental theorem of calculus,

. Finally, using the fundamental theorem of calculus,

![\begin{array}{ll}\int_0^\pi f(x)sin(x)\,dx\\[2mm]= \int_0^\pi \frac{d}{dx}\left[g^\prime(x)sin(x) - g(x)cos(x)\right]\,dx\\[2mm]= \left(g^\prime(\pi)sin(\pi) - g(\pi)cos(\pi)\right) - \left(g^\prime(0)sin(0) - g(0)cos(0)\right)\\[2mm]= \left(g^\prime(\pi)(0) - g(\pi)(-1)\right) - \left(g^\prime(0)(0) - g(0)(1)\right)\\[2mm] = g(\pi)+g(0)\end{array} \begin{array}{ll}\int_0^\pi f(x)sin(x)\,dx\\[2mm]= \int_0^\pi \frac{d}{dx}\left[g^\prime(x)sin(x) - g(x)cos(x)\right]\,dx\\[2mm]= \left(g^\prime(\pi)sin(\pi) - g(\pi)cos(\pi)\right) - \left(g^\prime(0)sin(0) - g(0)cos(0)\right)\\[2mm]= \left(g^\prime(\pi)(0) - g(\pi)(-1)\right) - \left(g^\prime(0)(0) - g(0)(1)\right)\\[2mm] = g(\pi)+g(0)\end{array}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bll%7D%5Cint_0%5E%5Cpi+f%28x%29sin%28x%29%5C%2Cdx%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D+%5Cint_0%5E%5Cpi+%5Cfrac%7Bd%7D%7Bdx%7D%5Cleft%5Bg%5E%5Cprime%28x%29sin%28x%29+-+g%28x%29cos%28x%29%5Cright%5D%5C%2Cdx%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D+%5Cleft%28g%5E%5Cprime%28%5Cpi%29sin%28%5Cpi%29+-+g%28%5Cpi%29cos%28%5Cpi%29%5Cright%29+-+%5Cleft%28g%5E%5Cprime%280%29sin%280%29+-+g%280%29cos%280%29%5Cright%29%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D%3D+%5Cleft%28g%5E%5Cprime%28%5Cpi%29%280%29+-+g%28%5Cpi%29%28-1%29%5Cright%29+-+%5Cleft%28g%5E%5Cprime%280%29%280%29+-+g%280%29%281%29%5Cright%29%5C%5C%5B2mm%5D+%3D+g%28%5Cpi%29%2Bg%280%29%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0)

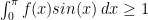

But this is an integer, and since f(x)sin(x)>0, this integer is at least 1. Therefore,  .

.

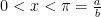

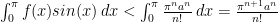

But check this out: if  , then

, then  .

.

Therefore,  . But here’s the thing; we can choose n to be any positive integer we’d like. Each one creates a slightly different version of f(x), but everything up to this point works the same for each of them. While the numerator, π(πa)n, grows exponentially fast, the denominator, n!, grows much much faster for large values of n. This is because each time n increases by one, the numerator is multiplied by πa (which is always the same), but the denominator is multiplied by n (which keeps getting bigger). Therefore, for a large enough value of n we can always force this integral to be smaller and smaller. In particular, for n large enough,

. But here’s the thing; we can choose n to be any positive integer we’d like. Each one creates a slightly different version of f(x), but everything up to this point works the same for each of them. While the numerator, π(πa)n, grows exponentially fast, the denominator, n!, grows much much faster for large values of n. This is because each time n increases by one, the numerator is multiplied by πa (which is always the same), but the denominator is multiplied by n (which keeps getting bigger). Therefore, for a large enough value of n we can always force this integral to be smaller and smaller. In particular, for n large enough,  . Keep in mind that

. Keep in mind that  is assumed to be some definite number, so it can’t “race against n”, which means that this fraction always becomes smaller and smaller.

is assumed to be some definite number, so it can’t “race against n”, which means that this fraction always becomes smaller and smaller.

Last step! We can now say that if π can be written as  , then a function, f(x), can be constructed such that

, then a function, f(x), can be constructed such that  and

and  . But that’s a contradiction. Therefore, π cannot be written as the ratio of two integers, so it must be irrational, and irrational numbers have non-repeating decimal expansions.

. But that’s a contradiction. Therefore, π cannot be written as the ratio of two integers, so it must be irrational, and irrational numbers have non-repeating decimal expansions.

Boom. That’s a proof.

For those of you still reading, it may occur to you to ask “wait… where did the properties of π get into that at all?”. The proof required that sine and cosine be derivatives of each other, and that’s only true when using radians. For example,  when x is in degrees. So, the proof requires that

when x is in degrees. So, the proof requires that  , and that requires that the angle is given in radians. Radians are defined geometrically so that the angle is described by the length of the arc it traces out, divided by the radius. Incidentally, this definition is equivalent to declaring the small angle approximation:

, and that requires that the angle is given in radians. Radians are defined geometrically so that the angle is described by the length of the arc it traces out, divided by the radius. Incidentally, this definition is equivalent to declaring the small angle approximation:  .

.

The radian.

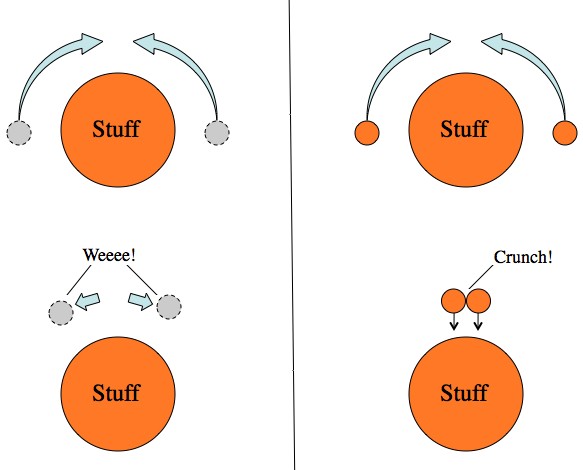

This defines the angle of a full circle as 2π radians and as a result of geometry and the definitions of sine and cosine, sin(π radians) = 0, cos(π radians) = -1,  , and that’s enough for the proof!

, and that’s enough for the proof!

Subtle, but behind all of that algebra, is a bedrock of geometry.