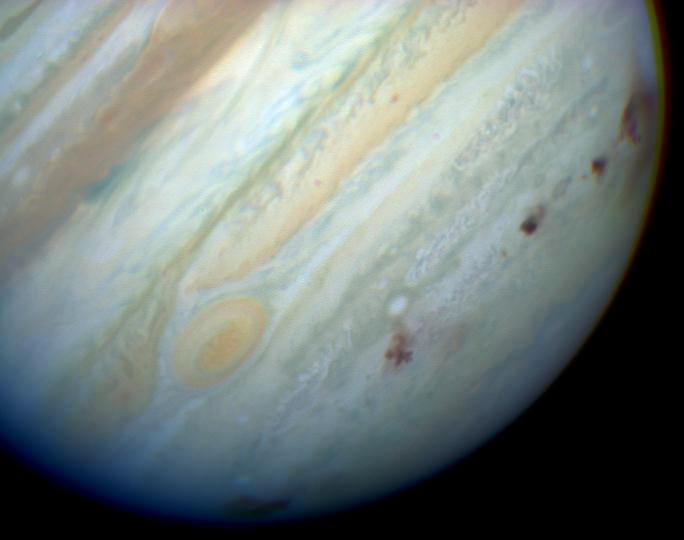

Physicist: There’s a long history of big things in the solar system slamming into each other. Recently (the last 4.5 billion years or so) there haven’t been a lot of planetary collisions, but there are still lots of “minor” collisions like the Chicxulub asteroid 65 million years ago that caused that whole kerfuffle (65,000,000 years is practically this morning compared to the age of the solar system), or comet Shoemaker Levy 9 which uglied up Jupiter back in 1994.

Jupiter after a run-in with Shoemaker Levy 9. Each of those black clouds on the lower right is caused by the impact of a different chunk of the same comet, and each is bigger than Earth.

So while planets slamming or nearly slamming into each other isn’t a serious concern today, it was at one time. Of course, in solar systems where this is still a serious concern, there’s unlikely to be anything alive to do the concerning.

For the sake of this post, let’s say there’s another planet, “Htrae”, that is the same size and approximate composition of Earth (but possibly populated entirely with evil goatee-having doppelgangers with reversed names).

A direct impact, or even a glancing impact, is more or less what you might expect: you start with two planets and end with lots of hot dust. We’re used to impacts that dent or punch through the crust of the Earth, but really big impacts treat both planets like water droplets. Rather than crushing together like lumps of clay, Earth and Htrae would “splash” off of each other. A direct impact of two like-masses tends to destroy them both. A glancing, well-off-center, impact will “stir” both planets, leaving no none of the original surface on either. A glancing impact like this is the best modern theory of the origin of the Moon.

If Htrae were to fall out of the sky, it would probably hit the Earth with a speed that’s on the same scale as Earth’s escape velocity: 11 km/s (Probably more). The time between when Htrae appears to be about the same size as the Sun or Moon, to when it physically hits the surface, would be a couple of weeks (give or take a lot). The time between hitting the top of the atmosphere and hitting the bottom would be a few seconds. If you were around, you would see Htrae spanning from one horizon to the other. A few moments before impact the collective atmospheres of both planets would glow brightly as they are suddenly compressed. It’s more likely that in those last few seconds/moments you would be vaporized from a distance by the heat and light released by the impact, and less likely that you would be crushed. People on the far side of Earth wouldn’t fare much better. They’d get very little warning, and would have to suddenly deal with the ground, and everything on it, suddenly being given a kick from below big enough to go flying into space.

Generally speaking, being slapped by the ground so hard that you find yourself in deep space a few minutes later is seriously fatal.

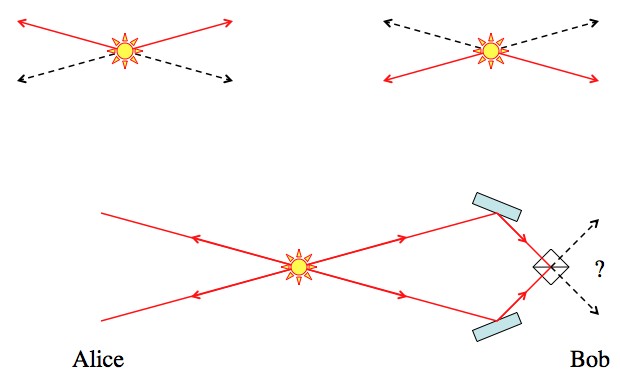

A near miss is a lot less flashy, but you really wouldn’t want to be around for that either. When you’re between two equal masses, you’re pulled equally by both. You may be standing on the surface of Earth, but most of it is still a long way away (about 4,000 miles on average). So if Htrae’s surface was within spitting distance, then you’d be about 4,000 miles from most of it as well. Nothing on the surface of Earth has any special “Earth-gravity-solidarity”, so if you were “lucky” enough to be standing right under Htrae as it passed overhead, you’d find yourself in nearly zero gravity.

Of course, there’s nothing special about stuff that’s on the surface either. The surface itself would also start floating around, and the local atmosphere would certainly take the opportunity to wander off. On a large scale this is described by the planets being well within each others’ Roche limit, which means that they literally just kinda fall apart. It’s not just that the region between the planets is in free fall, it’s that halfway around the worlds gravity will suddenly be pointing sideways quite a bit. So, what does a land-slide the size of a planet look like? From a distance it’s likely to be amazing, but you’re gonna want that distance to be pretty big.

Even a near miss, with the planets never quite coming into contact, does a colossal amount of damage. There would be a cloud of debris between and orbiting around both planets (or rather around both “roiling molten masses”) as well as long streamers of what used to be ocean, crust, and mantle extending between them as they move apart. This has never been seen on a planetary scale, since all the things doing the impacting these days barely have their own gravity. The highest vertical leap on a comet would be infinity (if anyone were to try).

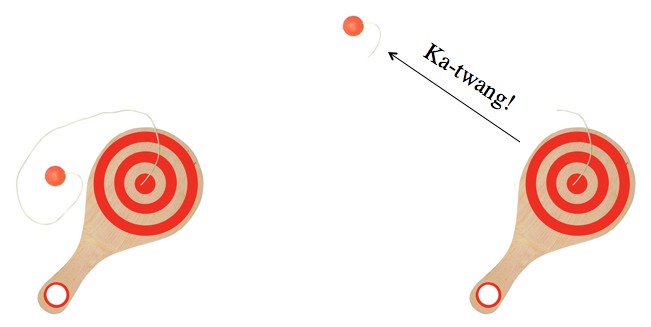

But the news gets worse. Unless both planets have a good reason to be really screaming past each other (maybe they were counter-orbiting or Htrae fell inward from the outer solar system or something), a near miss is usually just a preamble for a direct impact. All of the damage and scrambling that Earth and Htrae did do each other took energy. That energy is taken mostly from the kinetic energy, so after a near miss the average speed of the two planets would be less than it was before. And that means that the planets often can’t escape from each other (at least not forever). In fact, this is why Shoemaker Levy 9 impacted Jupiter a dozen times instead of all at once. Before impacting, the comet had passed within Jupiter’s Roche limit (probably several times), been pulled into a streamer of rocks, and slowed down.