Astronomer: Most black holes form when a star which is ten times more massive than our Sun runs out of fuel for fusion. This causes the star to collapse, explode as a supernova, and, if enough material is left over after the explosion, becomes what is called a stellar black hole. A black hole is an object with such a high density that even light doesn’t travel fast enough to escape its gravity. Something that falls into a black hole can never escape, because nothing can travel faster than the speed of light.

What would happen if one of these stellar black holes wandered into our solar system? Very Bad Things. The first indication we might get that something unusual was happening would be subtle changes in the orbits of the outer planets. These changes would be detectable at least by the time the black hole was a few hundred thousand times the distance between the Earth and the Sun.

By then the black hole would be near the outer reaches of the solar system, in an area filled with icy comet-like objects called the Oort cloud. It’s possible that the gravitational disruption caused by the black hole traveling through the Oort cloud could gravitationally catapult a large number of additional comets into the inner solar system, some of which might strike Earth or other planets. If the black hole passed through only this outer part of the solar system, for example if it were moving too fast to be strongly affected by the Sun’s gravitational influence, an increase in comets in the inner solar system might be the only effect we would observe.

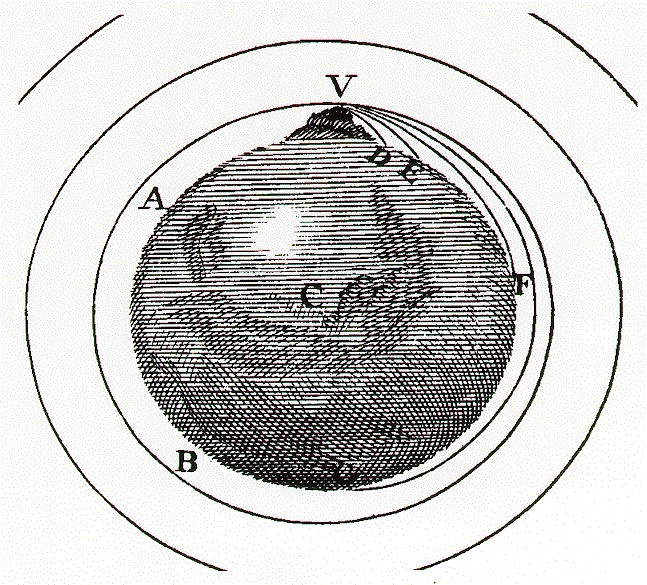

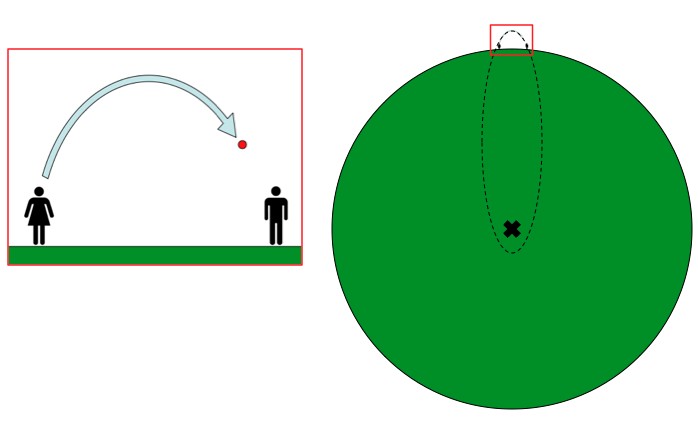

At this point we likely wouldn’t see anything at the black hole’s position, even if we looked with the best available telescopes. The black hole itself doesn’t doesn’t give off light, and the only way we might detect it is through the energy released when it consumes some gas. Even the black hole’s affect on the light from stars behind it – which causes the light to be bent into an apparent ring around the black hole – would be too small for us to see. Only until the black hole reaches the inner edge of the asteroid belt would we be able to directly observe the light-bending effects of the black hole. By this point, the effects on the Earth’s orbit would be extreme and it’s likely the black hole would have become visible through its interaction with one of the outer planets.

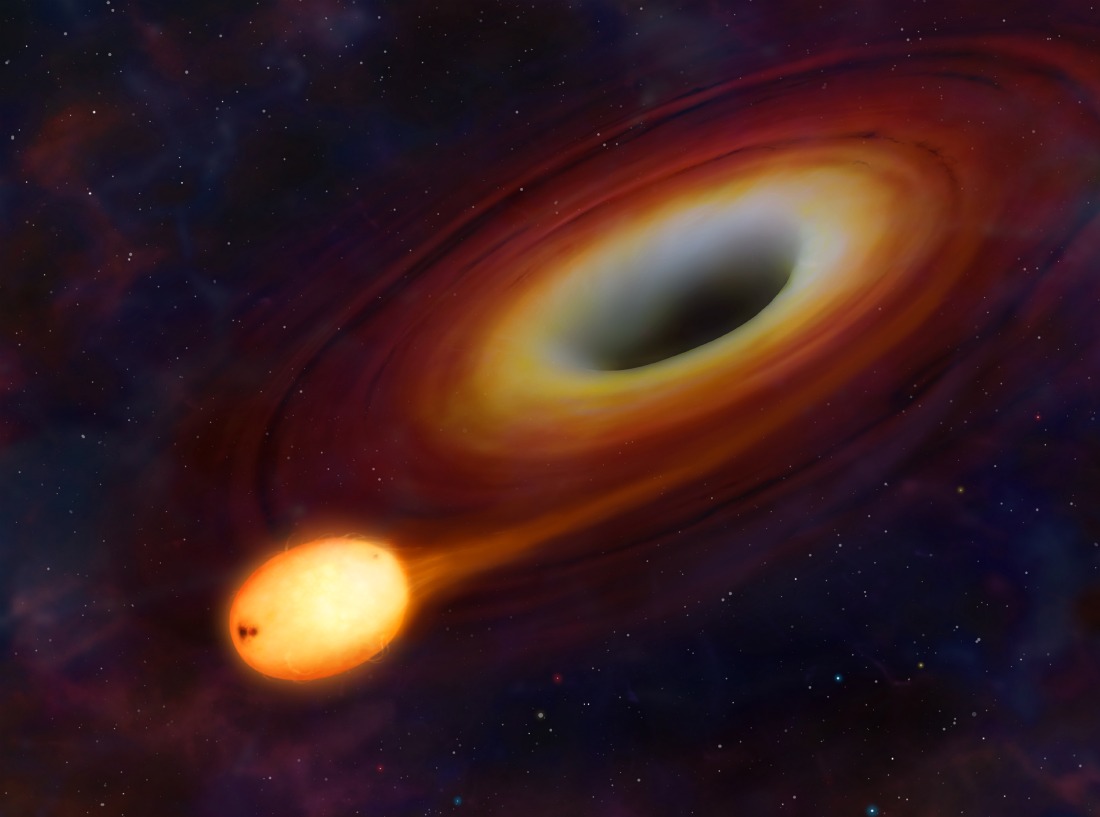

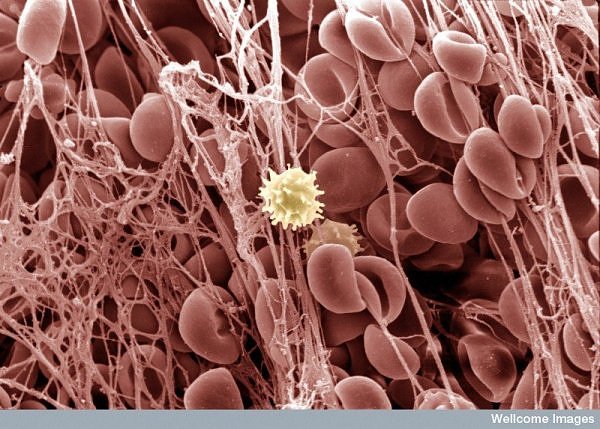

If the black hole continued to move toward the inner solar system, the orbits of the planets would continue to be disrupted in dramatic ways. Jupiter, the most massive planet, might be snared by the black hole due to their strong mutual gravitational attraction. The black hole would pull gas from Jupiter, forming a bright disk of swirling, hot gas. The hot gas disk gives off x-ray radiation. Despite the fact that Jupiter is thousands of times larger than the black hole, the black hole is thousands of times more massive than Jupiter and easily wins. Jupiter is entirely consumed onto the relatively tiny black hole.

By this time, the Earth is already in grave trouble. The gravitational effects of the black hole have caused earthquakes and volcanic eruptions more extreme than those ever seen before by humans. The Earth would be pulled out of its usual orbit, possibly experiencing abrupt changes in direction or being pulled away or towards the Sun. By the time the black hole crosses Earth’s orbit the geologic effects from tidal forces will have effectively repaved the Earth’s surface with magma and wiped out all life. Since the Sun contains 99.9% of the mass of the solar system, the Sun and the black hole experience a strong gravitational pull towards each other. The black hole would approach the Sun, whose gas is stripped and pulled into the black hole. The Earth, whose inhabitants have already died, would approach the sun/black hole pair, heat up, be torn apart by gravitational forces, and then be pulled into the black hole itself.

Now that we’ve set this morbid scene, you might wonder how likely is it that a black hole will wander into our solar system, causing widespread death and destruction. Here, at least, we have some good news. With what we know today, it seems exceedingly unlikely to happen anywhere in the galaxy (except at the very center), much less our own solar system. Distances between black holes are huge, and the density of black holes is less because we are in the outer third of our galaxy. In addition, most black holes aren’t zipping around the galaxy at high speed, which makes them far less likely to encounter a solar system.

(picture credit: University of Warwick/ Mark A. Garlick)