Physicist: If you’re a fan of Star Wars you may remember proton torpedoes from Episode IV as the only weapon that, when fired down an exposed thermal exhaust port on the Death Star, would “…start a chain reaction which should destroy the station.“, because obviously “The shaft is ray-shielded, so you’ll have to use proton torpedoes.“.

Fans of Star Trek, on the other hand, think they just read “photon torpedoes” twice.

According to the perfectly named Wookieepedia, proton torpedoes release clouds of high energy protons on impact. Now technically, that’s what all explosives do. By mass, atoms are almost entirely made of protons and neutrons, each of which are around 2000 times more massive than electrons, and (for most elements) show up in roughly equal numbers. So about half of the mass of practically anything is protons (the glaring exception is hydrogen, which is 1 proton and 1 electron).

Incidentally releasing clouds of protons, because that’s what’s in clouds of anything, is clearly not the idea behind proton torpedoes nor the spirit of this question. Neutron bombs (which are real things) release a heck of a lot of neutrons and not too much else. Proton torpedoes should be like neutron bombs, just with protons.

Once again physics, the queen of sciences and mother of buzzkills, has things to say. The thing about protons is that long before you notice them doing damage by physically impacting things, you notice their electrical charge. A proton is like a mosquito when you’re trying to sleep; the mass is not what’s important.

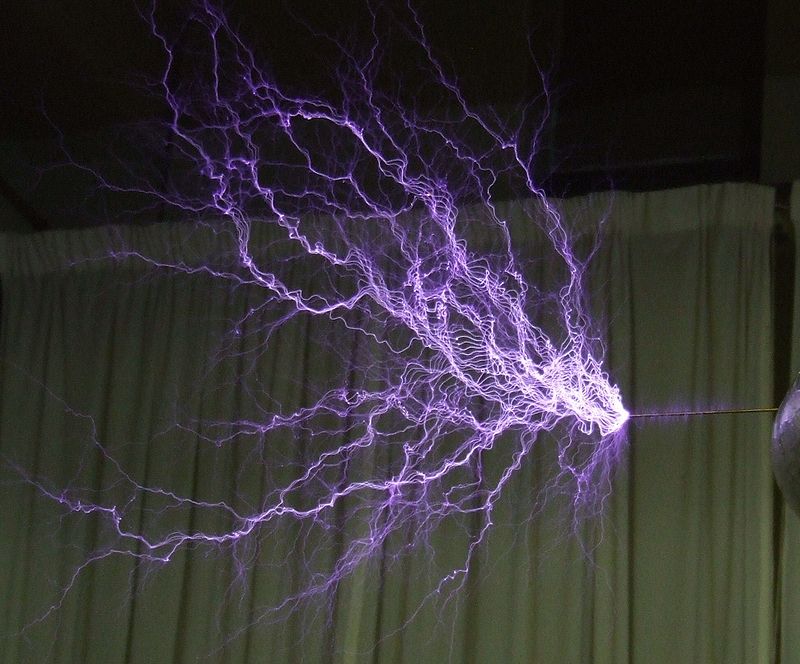

There are incomprehensible electrical charges buried inside of everything, we just don’t notice them because they’re normally almost perfectly balanced. One gram of protons, without accompanying electrons to bring their net charge to zero, would create an electric field strong enough strip electrons from their host atoms and ionize air more than 15 km away. It wouldn’t be too healthy for any other materials either; a field this large and intense could pull lightning bolts through granite at a range of 10 km.

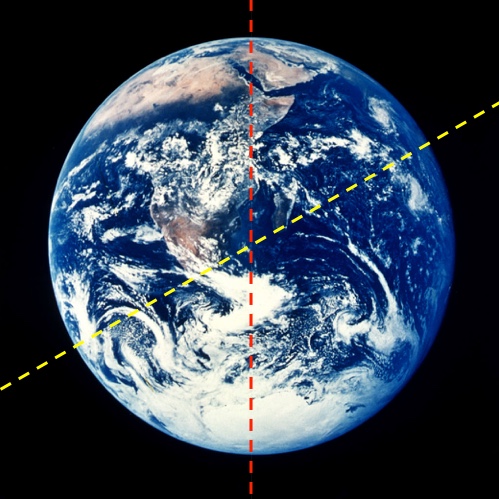

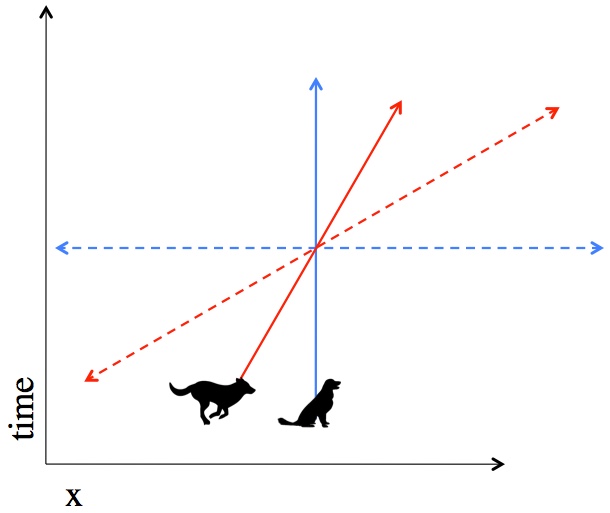

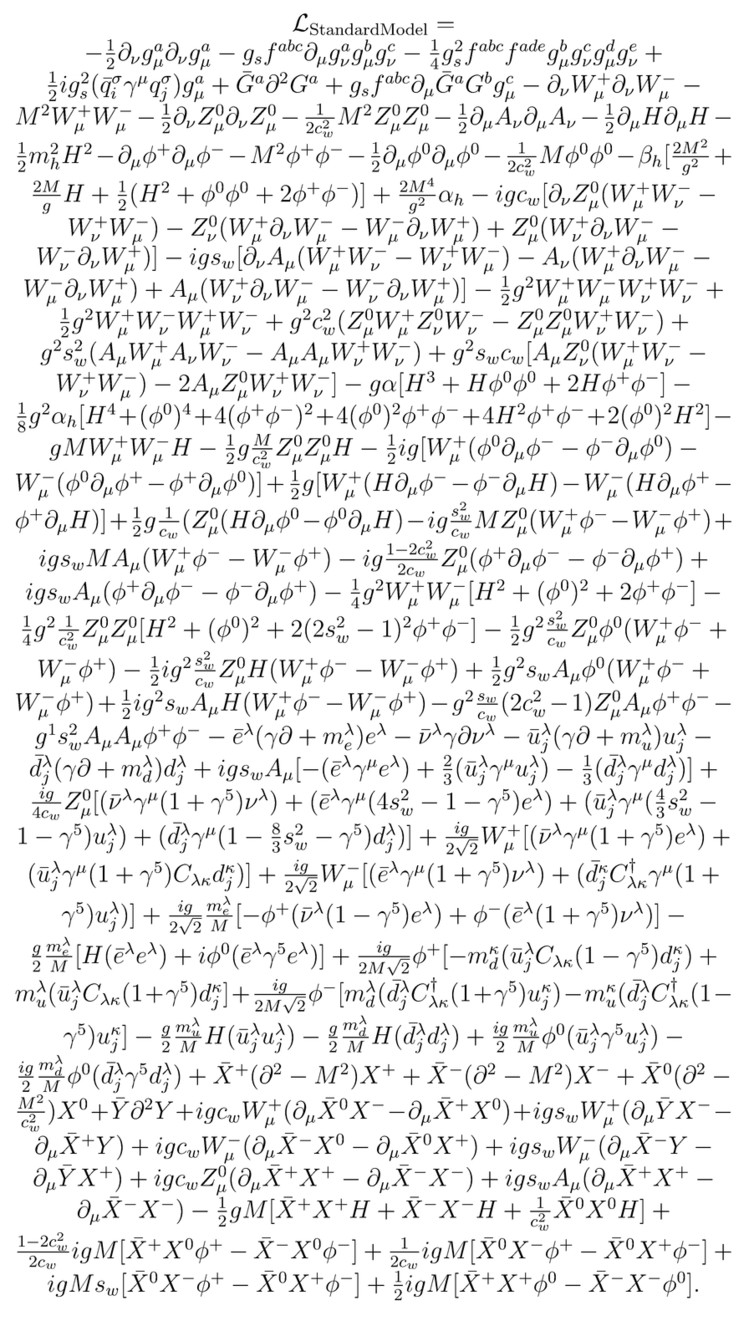

In the immediate vicinity of this Tesla coil the electric field exceeds the 3kV/mm needed for air to spontaneously ionize (hence the faint glow around the rod).

So a proton torpedo with a one gram payload does a heck of a lot of damage just by existing. Luke’s aim didn’t really need to be that good.

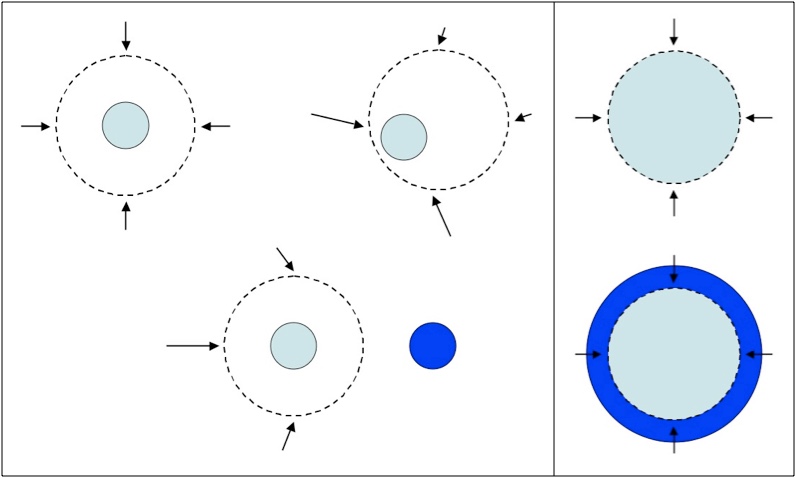

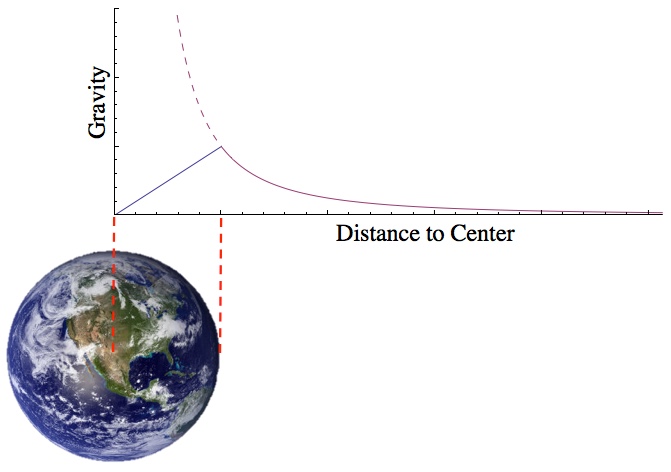

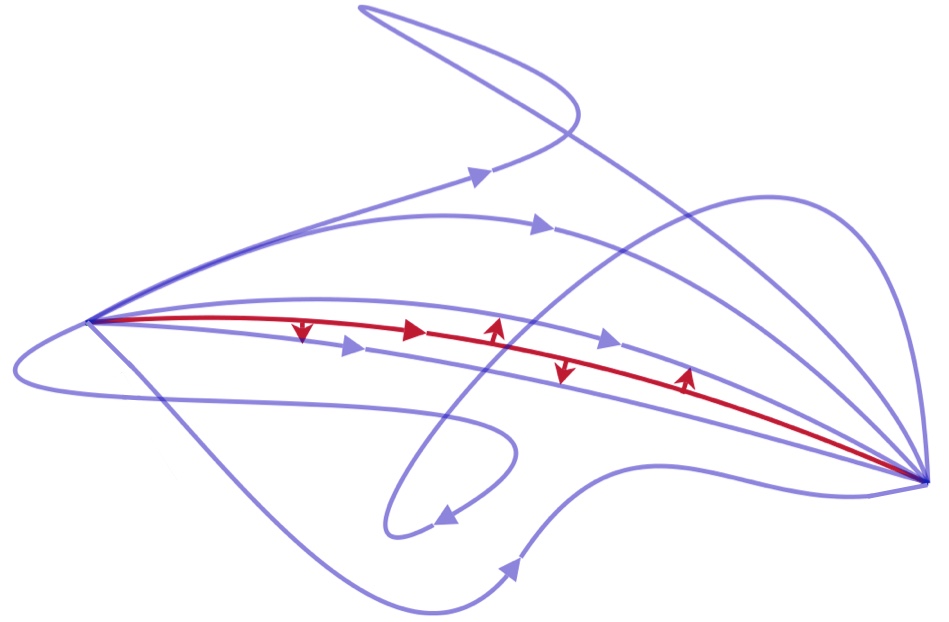

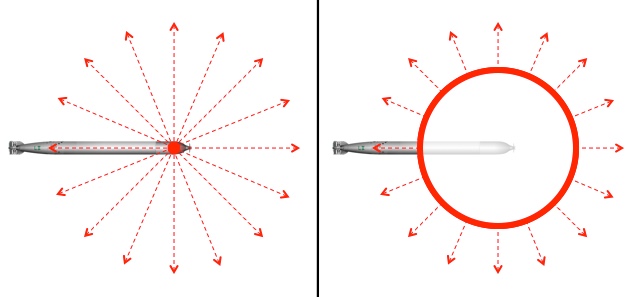

Ironically, the big effect of detonating the torpedo and releasing the protons is that the electric field actually drops. As the last post talked about too much, you can understand a lot about electric and gravitational fields by “drawing bubbles” around them. The total field flowing out of a bubble is proportional to the amount of charge inside of that bubble. So if you’re standing far enough away, the field you feel stays about the same whether or not the torpedo has exploded. As the shell of protons expands and repels itself, the field outside of it stays about the same while the field inside of it disappears. If you’re up close, when the expanding shell of protons passes you (assuming you’re alive) you’d find yourself in a region with little or no electric field. The most destructive thing you can do with a pile of protons is not blow it up, but keep it together in as small a place as possible.

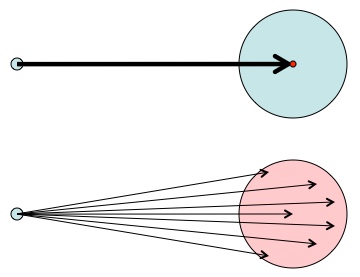

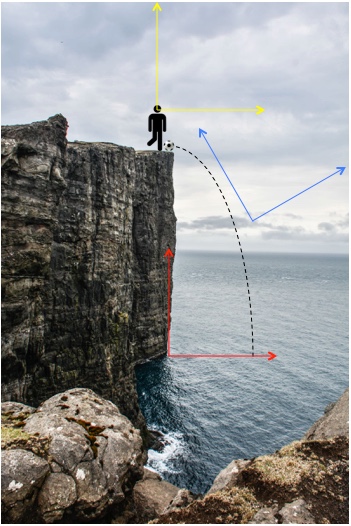

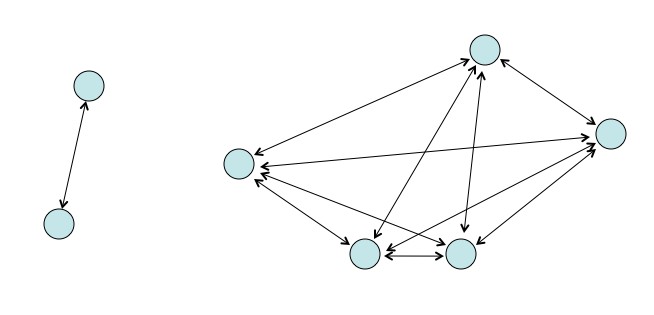

Left: A torpedo (or anything else) with an excess of positively-charged protons produces an electric field. Right: As the shock front of proton shrapnel expands, the field outside stays about the same while the field inside drops to around zero.

The only way to block the electric field created by a bucket of charge is to surround it with the same amount of the opposite charge. Both positive and negative charges create electric fields, but those fields counteract each other. That’s why, despite containing many kg of protons, you doesn’t destroy everything around you.

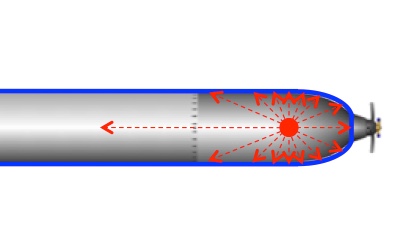

Unfortunately for BlasTech Industries (famed maker of clumsy, random blasters), counteracting electric fields is exactly what charges always do, given the chance.

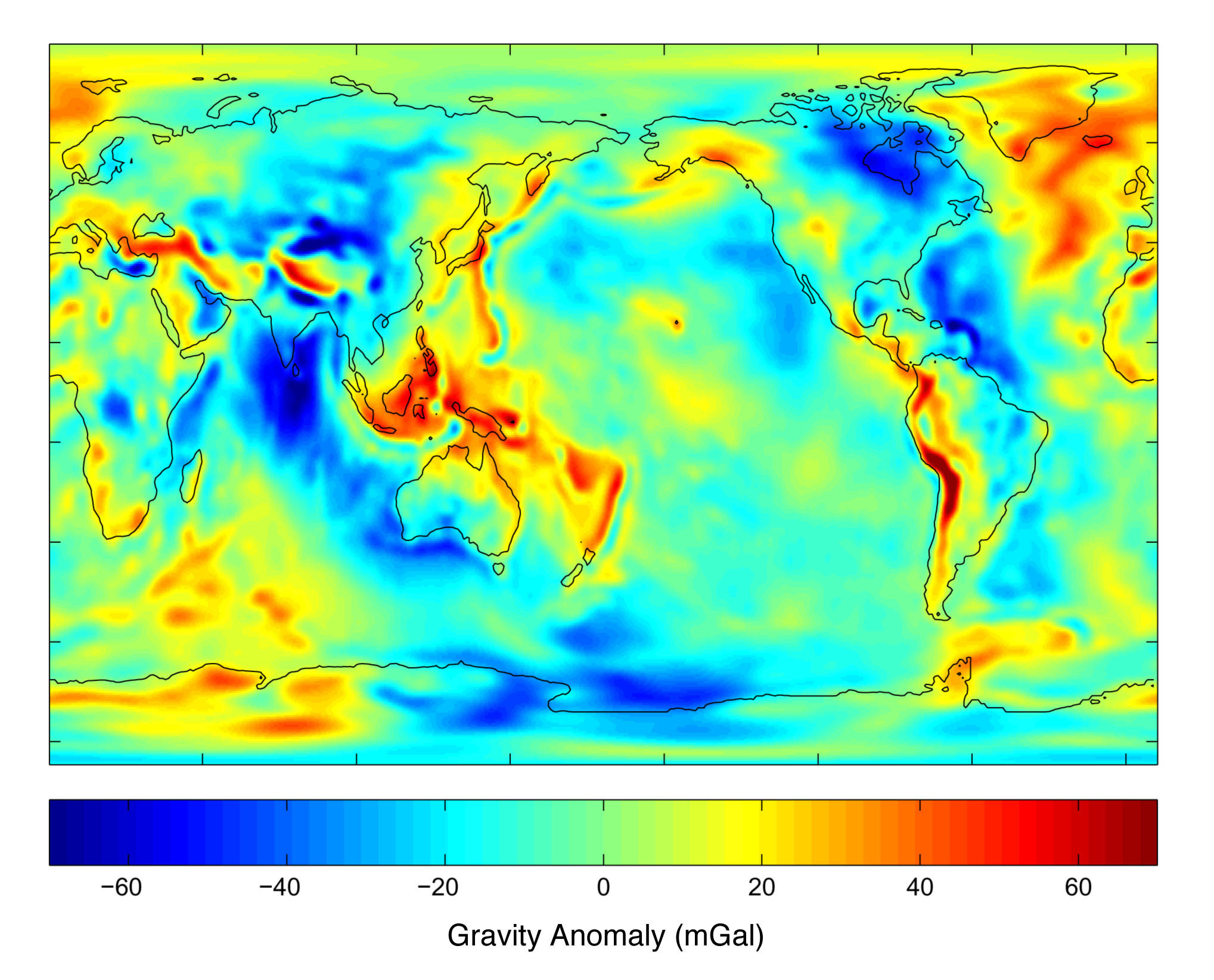

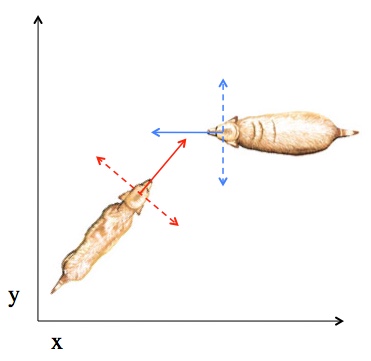

Negative charges (blue) flow toward positive charges (red), because that’s what charges do, until they balance. Once they do, the net electric field outside the torpedo is zero.

So even if you intentionally store protons in you proton torpedo with the hope of weaponizing its electric field, the first thing that will happen is any nearby matter will ionize. The loosed electrons will fly toward and coat the torpedo while the stripped nuclei (which are full of protons) beat a hasty retreat. Assuming the casing is a perfect insulator, in the end you’d have a torpedo with a gram of extra protons inside, about half a milligram of electrons outside (because electrons are about 2000 times less massive than protons), and no devastating electric field.

You could keep the protons and electrons together until the torpedo hits its target, then release the protons but keep the electrons in place (I mean… somehow). Then you could transport your munitions without preemptively killing everything around them. But that would be like firing bullets tied to (very strong) rubber bands; the electrons and protons would rather fly back together than do anything else.

So “proton torpedo” may just be a code name like “tomahawk missile” (noteworthy for its lack of tomahawks). That, or George Lucas is playing a little fast and loose with physics.